The Use of Syāmē as a Phonological Marker in Syriac

For J. F. ‘Chip’ Coakley on his retirement

It is well established that the primary use of syāmē in Syriac is to mark the morphological category of plurality. This study explores a secondary use of syāmē. This occurs most frequently with grc words in Syriac that ended in -η, or more rarely -ε or -αι, in the Greek source. It is proposed that the phonological use of syāmē can also explain the regularity and consistency with which syāmē occur with the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers.

It is well established that the primary use of syāmē ‘(lit.) placings’ in Syriac is to mark the morphological category of plurality. 1 The pb. 96 singular noun ܡܠܟܐ /malkā/ ‘king’, for instance, is distinguished ܡܠܟ̈ܐ /malkē/ ‘kings’ in the consonantal script of Syriac by the syāmē on the latter. 2 This use of syāmē is attested already in the earliest Syriac manuscripts, such as London, Brit. Libr. Add. 12,150, which is dated to 411 CE. 3 It should be noted thatsyāmēare not found in the Old Syriac inscriptions, e.g., ܒܢܝ /bnay/ ‘my children’ (As16 [201/2 CE]; ed. Drijvers and Healey 1999: 73-74), or in the Old Syriac documents, e.g., ܙܒܢܝܢ /zabnin/ ‘times’ (P1.7 [243 CE]; ed. Drijvers and Healey 1999: 73-74). 4 While syāmē mark the morphological category of plurality in the vast majority of cases, this is not their only use in Syriac. Occasionally, syāmē function as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel in Syriac.

The occasional use of syāmē as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel is most common with Greek loanwords in Syriac that ended in -η in the Greek source, as in the following examples: 5

pb. 97(1)

- a. ἀνάγκη (Liddell and Scott 1996: 101) > ܐܢܢܩ̈ܐ ‘necessity’ in ܐܢܢܩ̈ܐܬܚܝܬ ܗ̣ܝ ܟܕ ܗ̣ܝ ܐܢܢܩ̈ܐ ܢܦ̈ܠܢ 'they fall under the same necessity’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Cause of the Liturgical Feasts, 103.20; ed. Macomber 1974).

- b. διαθήκη (Lampe 1961: 348; Liddell and Scott 1996: 394-395) > ܕܝ̈ܬܩܐ 'covenant' in ܢܘܟܪܝܐ ܕܕܝ̈ܬܩܐ ܫܡܝܢܝܬܐ ‘stranger to the heavenly covenant’ ((History of St. Cyriacus and his Mother Julitta according to the Syriac ms. at the Library of the Royal Asiatic Society, f. 182r, ln. 10 [1569 CE]), 6 in ܕܝ̈ܬܩܐ ܥܬܝܩܬܐ 'Old Testament’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Cause of the Liturgical Feasts, 20.26-21.1, 73.17,92.17, 109.23, 171.6, 172.17-18; ed. Macomber 1974); 7 ܦܬ ܓܡ̈ܐ ܕܕܝܬܩ̈ܐ ܗܕܐ 'the words of this covenant’ (Jer. 11:6; Mosul edition).

- c. νομή (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1178-1179) > ܢܘ̈ܡܐ 'pasture' in ܐܚܕܬ ܗܘܬ ܢܘ̈ܡܐ ܝܗܝܒܘܬܗ ܕܢܡܘܣܐ ‘the giving of the law had spread out’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Cause of the Liturgical Feasts, 171.12-13; ed. Macomber 1974). 8

- d. πεντηκοστή (Lampe 1961: 1060) > ܦܢܛܩܘ̈ܣܛܐ in ’Pentecost‘ ܡܢܐ ܡܒܕܩ ܫܡܐ ܗܢܐ ܕܦܢܛܩܘ̈ܣܛܐ pb. 98 ‘what does this word “Pentecost” signify’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts, 160.4; 161.13; 162.4-5; ed. Macomber 1974). 9

- e. σχολή (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1747-1748) > ܐܣܟܘ̈ܠܐ ‘school’ in ܪ̈ܒܢܐ ܕܟܢܘܫܢܝܐ ܕܐܣܟܘ̈ܠܐ ܩܕܝܫܬܐ ܕܢܨܝܒܝܢ ‘the teachers of the community of the holy School of Nisibis’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts, 45.24; ed. Macomber 1974). 10

- f. τροφή (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1827-1828) > ܛܪ̈ܘܦܐ 'support, nourishment' in ܘܚܘܪܪܐ ܕܡܢ ܚ̈ܫܐ ܛܪ̈ܘܦܐ ܕܗܝ ܐܝܬܝܗ̇ ܕܟܝܘܬܐ nourishment, which is purity and freedom from suffering’ (Babai the Great, Commentary on the ‘Gnostic Chapters’ by Evagrius of Pontus, Pontus, 468.14-15; ed. Frankenberg 1912).

- g. ὕλη (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1847-1848) > ܗܝܘ̈ܠܐ 'matter‘ in ܘܡܥܠܝܢ ܗܝܘ̈ܠܐ ܥܠ ܒܪܘܝܘܬܐ ܐܠܗܝܬܐ ‘they introduce matter to the divine creation’ (Qiyore of Edessa, Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts, 20.18-19; ed. Macomber 1974). 11 11

- h. φυλακή (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1960) > ܦܘ̈ܠܩܐ ‘prison’ in ܟܕ ܒܦܘ̈ܠܩܐ ܡܬܢܛܪ ܗܘܐ ܡܝܬ ‘when he was being guarded in the prison, he died’ (Yuḥanon of Ephesus, Ecclesiastical History, Part 3, 158.22; ed. Brooks 1935). 12

It should be noted that forms without syāmē are much more common for all of these words. Regardless, in each of the cases in (1), the syāmē serve as a phonological marker for a final mid front pb. 99 vowel. The writing ofsyāmē, thus, disambiguates the consonantal script of these Greek loanwords, which could be read with either final -ā or final -ē, in the same way as it disambiguates the consonantal script of many masculine nouns, e.g., singular ܡܠܟܐ /malkā/ ‘king’ vs. plural ܡ̈ܠܟܐ /malkē/ ‘kings’. The list in (1) is not exhaustive, but it would seem to provide enough evidence to establish that syāmē occasionally occur as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel in Syriac reflecting -η in the Greek source. 13

Syriac syāmē also serve as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel with several Greek proper nouns that ended in -η, as in the following examples: 14

(2)

- a. Κρήτη ‘Crete’ > ܩܪ̈ܛܐ (Zeph 2:5, 6; Leiden edition).

- b. Σκήτη ‘Skete’ > ܐܣܩ̈ܛܐ (History of Abba Marcus of Mt. Tharmaka, according to ms. Yale Syriac 5, p. 36; e. Look 1929: 1).

These cases are comparable to those cited in (1) in which syāmē disambiguate the consonantal script, which could be read with either final -ā or final -ē.

The use of syāmē as a phonological marker for final Greek η has implications for the pronunciation of η in the Koinē Greek of Syria and Mesopotamia. In Attic Greek, η was a long open-mid front /ε:/. 15 Some Koinē dialects preserved η as an open-mid front /ε/ into the Roman period, whereas others attest a merger of η with the high front /i/, which could be written either ι or ει. 16 A few spellings in the Greek documents from Syria and Mesopotamia suggest that Greek η was at least beginning to merge to /i/ in this region by the Roman period. 17 The use of syāmē as a phonological pb. 100 marker for final Greek η, however, suggests that some Syriac writers and/or scribes preserved a pronunciation of η as a mid front vowel well into the Roman period, since the Syriac masculine plural status emphaticus ending was never realized as a high front vowel but always as mid front. The preservation of a mid front pronunciation of Greek η in this area at this time can be corroborated by the representation of final Greek -η by the voiceless glottal stop ʾ in Syriac, which would have represented a final mid front vowel, in contrast to spellings with a final palatal glide y, which would have represented a final high front vowel, e.g., ἀνάγκη (Liddell and Scott 1996: 101) > ܐܢܢܩܝ ،ܐܢܢܩܐ necessity’ (Sokoloff 2009: 63). Thus, Syriac evidence suggests that Greek η was beginning to merge to /i/ in this region by the Roman period (representations of final η with Syriac y), though at least some Syriac writers and/or scribes preserved its mid front realization well into the Roman Period (representations of final -η with Syriac ʾ and the occasional use of syāmē as a phonological marker). 18

In addition to final Greek -η, syāmē more rarely serve as a phonological marker for final Greek -ε. This is, for instance, the case with the writing of the personal name ܩܝܘܪ̈ܐ ‘Qiyore’ in the Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts by Qiyore of Edessa (1.1; ed. Macomber 1974). This Syriac name derives from Greek Κῦρε, a frozen vocative of Κῦρος ‘Cyrus’. Thus, in this case, the syāmē in pb. 101 ܩܝܘܪ̈ܐ mark the final -ε in Κῦρε. A similar use of syāmē occurs with the writing of the Greek aorist passive infinitive σφυρισθῆναι ‘to be struck with hammers, beat’ as ܐܣܦܪ̈ܣܬܝܢܐ with syāmē in Part 3 of the Ecclesiastical History by Yuḥanon of Ephesus (15.28; ed. Brooks 1935). In the editio princeps, Brooks proposed to emend this word by removing syāmē. This emendation is, however, unnecessary, since the syāmē here are a phonological marker for final Greek -αι, which had merged with Greek ε as a mid-front short /e/ by the Koinē Greek of the Roman and Byzantine periods. 19

An interesting case of the use of syāmē for Greek -ε is found in the following passage from the anonymous tract on accents in Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138 (899 CE), which is the only surviving manuscript of the East-Syriac ‘Masora’: 20

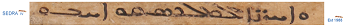

(3) Anonymous tract in East-Syriac ‘Masora’ (Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138 [899 CE]) ܁ ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ ܠ̇ܐܵ ܬܹܕ݂ܚܲܠ ‘Do not be afraid, Paul’ (f. 306v, ln. 17 = Acts 27:24) 21

The p in ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ has five points above it: a quššāyā point, an East- Syriac zqāpā with two points, as well as two additional points. 22 pb. 102 Segal follows the author of the anonymous tract in interpreting these two additional points as a rāhṭā accent, which ‘joins two words closely together in a context to which a rising tone is suitable’ (1953: 98-99). A similar interpretation is found in Kiraz’s recent volume on Syriac orthography, where it is added that the two points are ‘not to be confused’ with syāmē (2012: §139). This analysis is, however, not without problems. The use of rāhṭā at the end of a word is found in a fair number of reliable examples. 23 In contrast, the use of rāhṭā at the beginning of a word is not so reliably attested. Following the anonymous tract on accents in Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138, Segal (1953: 99) provides three total examples, but comments that ‘in all these examples one of the two points may not be part of rāhṭā but a diacritical point’ (n. 7). Given the uncertainty over the use of rāhṭā at the beginning of a word, an alternative analysis of the two additional points in ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ in (3) is in order. These two points could represent syāmē being used as a phonological marker. In this case, the syāmē would represent the final -ε in the Greek vocative Παῦλε.

If the syāmē in ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ in (3) are analyzed as a phonological marker for final -ε, the Syriac vocalization with final ptāḥā would then be a secondary development. In his Book of Splendors, Bar ʿEbroyo (d. 1286) explains that Greek personal names in Syriac that end in -os have a vocative in -e, e.g., ܦܘܠܶܐ <Παῦλε) vocative of ܦܘܠܘܣ (<Παῦλος), and that those that end in -as have a vocative in -a, e.g., ܡܰܐܡܰܐ ((<Μάμα) vocative of ܡܰܐܡܰܐܣ ((<Μάμας). 24 He then provides the following comment about the derivation of such words in East Syriac:

pb. 103(4) Book of Splendors by Bar ʿEbroyo (ed. Moberg 1922)

ܡܕܢܚ̈ܐ ܡ̇ܢ ܟܕ ܩܢܘܢܐ ܗܢܐ ܠܐ ܢܛܪܝܢ ܠܬܪ̈ܝܗܘܢ ܛܘ̈ܦܣܐ ܗܠܝܢ ܒܚ̈ܕܕܐ ܚܠܛܝܢ ܘܦܘܠܳܐ ܘܬܐܦܝܠܳܐ ܘܫܪܟܐ ܒܙܩܦܗܘܢ ܕܕܡܐ 25 ܠܦܬܚܐ ܩܪܝܢ...

‘The East Syrians, not keeping this rule, mix these two types with one another and read pwlā, tʾpylā, etc., with their zqāpā which resembles ptāḥā ...’ (66.23-24)

Thus, Bar ʿEbroyo states that the two Greek types -os and -as had been leveled to a single vocative in -ā in East Syriac by his time (the thirteenth century). The form ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ in the East-Syriac ‘Masora’ establishes that this leveling had occurred already by 899, several centuries prior to Bar ʿEbroyo. 26 It is difficult to explain the discrepancy between the final zqāpā given by Bar ʿEbroyo in his description of East Syriac and the final ptāḥā found in Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138. 27 It should, however, be noted that both final zqāpā and ptāḥā are found for these forms in the later East-Syriac tradition; the Mosul Bible, for instance, has ܬܹܐܘܿܦܝܼܠܵܐ (Luke 1:3) ending in zqāpā but ܦܝܼܠܝܼܦܲܐ (John 14:9) and ܦܵܘܠܲܐ (Acts 27:24) ending in ptāḥā.

Thus, it is proposed that the two additional points in ܦܵ̈݁ܘܠܲܐ – that is, those points that are neither the quššāyā marker nor the East-Syriac zqāpā – are best analyzed as syāmē. This syāmē would have functioned as a phonological marker for final -ε before East Syriac leveled the two types of vocatives of Greek personal names (-e and -a) to a single type in -a/ā. After the leveling, the syāmē would not have been analyzable, since the final vowel was no longer mid front. This would have made it possible for syāmē in this case to be reinterpreted as a rāhṭā accent, as they have been in the East-Syriac ‘Masora’ (Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138, f. 306v, ln. 17). 28

Up to this point, all of the examples of syāmē functioning as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel involve Greek words in Syriac. There is, however, a set of native Syriac words where syāmē also function as a phonological marker (or at least did originally): the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers (11-19). The most commonly attested forms of the teen cardinal numbers are given in the chart in (5).

(5)

| with masculine nouns | with feminine nouns | |

| 1 | ܚܕܰܥܣܰܪ | ܚܕܰܥܶܣ̈ܪܶܐ |

| 2 | ܬܪܶܥܣܰܪ | ܰܪ̈ܬܰܥܶܣܪܶܐ |

| 3 | ܬܠܳܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܬܠܳܬܰܥܶܣ̈ܪܶܐ |

| 4 | ܐܰܪܒܰܥܬܳܥܣܰܪ | ܐܰܪ̈ܒܰܥܶܣܪܶܐ |

| 5 | ܚܰܡܶܫܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܚܰܡ̈ܫܰܥܶܣܪܶܐ |

| 6 | ܫܬܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܫܬ̈ܬܰܥܶܣܪܶܐ |

| 7 | ܫܒܰܥܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܫܒܰܥܷ̈ܣܪܶܐ |

| 8 | ܬܡܳܢܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܬܡܳܢܰܥܷ̈ܣܪܶܐ |

| 9 | ܬܫܰܥܬܰܥܣܰܪ | ܬܫܰܥܷ̈ܣܪܶܐ |

In the manuscripts, there is a great deal of variation in the forms themselves as well as in which forms are written with syāmē 29 Notwithstanding this, however, syāmē are most commonly found with the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers. This is due to the fact that it is the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers that end in -ē. 30 This final -ē is not etymologically related pb. 105 to the Syriac masculine plural status emphaticus ending -ē. 31 Thus, the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers represent another pb. 106 case in which syāmē (at least originally) serve as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel in Syriac – this time with native Syriac words. The fact that syāmē are occasionally found with the masculine forms of the teen cardinal numbers, which do not end in -ē, as well as with other numbers, which also do not end in -ē suggests that the phonological use of syāmē was secondarily reinterpreted as a morphological marker of plurality by at least some writers and/or scribes. This, however, represents a secondary development. The regularity and consistency with which syāmē occur with the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers suggest that the origin of their use with numbers is to be found there, where they functioned originally as a phonological marker, and it is from there that they spread to other numbers. 32

The connection between syāmē and the end of a word is interestingly enough reflected in the orthography of the Syriac incantation bowls. 33 In contrast to the situation in Classical Syriac, syāmē often occur on the final ʾālap in the Syriac incantation bowls, e.g., ܫܐܕܐ̈ 'demons’ (Hamilton 1971: 98a [sub ln. 12]). 34 The same pb. 107 orthography is found in the Syriac leather amulets edited by Ph. Gignoux (1987), 35 e.g., ܫܐܕܐ̈ 'demons’ (Amulet 1, ln. 16). This orthography of writing syāmē on the last letter of the word indicates the close connection between syāmē and the phonology of the last syllable.

This study has aimed to shed light on a minor, but interesting orthographic feature of Syriac that is not recorded in the standard grammars, such as those of Duval (1881) and Nöldeke (1904): the occasional use of syāmē as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel in Syriac. 36 This use of syāmē is due to a reanalysis of the relationship between syāmē and the ending -ē of masculine plural status emphaticus nouns, such as ܡ̈ܠܟܐ /malkē/ ‘kings’. Some writers and/or scribes re-analyzed what was originally a morphological marker of plurality in nouns such as ܡ̈ܠܟܐ /malkē/ ‘kings' as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel. This reanalysis enabled syāmē to be extended to non-plural words that ended in a mid front vowel, such as Greek words in Syriac that ended in -η, or more rarely -ε or -αι in the Greek source as well as to the feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers. 37

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Allen, W. S. 1987. Vox Graeca: A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Greek (3rd ed.). Cambridge. .

- Becker, A. H. 2006. Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom. The School of Nisibis and Christian Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia. Philadelphia. .

- _______. “The Comparative Study of ‘Scholasticism’ in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Rabbis and East Syrians,” AJS Review 34: 91-113. .

- Bedjan, P. 1890-1897. Acta Martyrum et Sanctorum (7 vols.). Paris – Leipzig. .

- Bordreuil, P. and D. Pardee. 2009. A Manual of Ugaritic (LAWS 3). Winona Lake. .

- Brock, S. P. 1967. “Greek Words in the Syriac Gospels (vet and pe)," Le Muséon 80 (1967): 389-426. .

- Brock, S. P., A. M. Butts, G. A. Kiraz, and L. Van Rompay. 2011. Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway. .

- Brockelmann, C. 1908. Grundriß der vergleichenden Grammatik der semitischen Sprachen, Vol. I. Laut- und Formenlehre. Berlin. .

- _______. 1981. Syrische Grammatik (13th ed.). Leipzig. .

- Brooks, E. W. 1935. Iohannis Ephesini. Historiae Ecclesiasticae. Pars Tertia (CSCO 105). Louvain. .

- Chialà, S. 2011. Isacco di Ninive. Terza collezione (CSCO 637-638). Louvain. .

- Coakley, J. F. 2002. Robinson’s Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar (5th ed.). Oxford. Louvain. .

- Cowley, A. E. 1910. Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar (2nd ed.). Oxford.̮̮ .

- Degen, R. 1969. Altaramäische Grammatik (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden. .

- Drijvers, H. J. W. and J. F. Healey. 1999. The Old Syriac Inscriptions of Edessa and Osrhoene. Leiden. .

- Duval, R. 1881. Traité de grammaire syriaque. Paris. .

- Feissel, D. and J. Gascou. 1989. “Documents d’archives romains inédits du Moyen-Euphrate (IIIe siècle après J.-C.),” CRAI 1989: 535-561. .

- _______. 1995. “Documents d’archives romains inédits du moyen Euphrate (IIIe s. après J.-C.). I. Les pétitions (P. Euphr. 1 à 5),” Journal des Savants: 65-119. .

- _______. 2000. “Documents d’archives romains inédits du moyen Euphrate (IIIe s. après J.-C.). III. Actes diverses et lettres (P. Euphr. 11 à 17),” Journal des Savants: 157-208. .

- Feissel, D., J. Gascou, and J. Teixidor. 1997. “Documents d’archives romains inédits du moyen Euphrate (IIIe s. après J.-C.). II. Les actes de vente-achat (P. Euphr. 6 à 10),” Journal des Savants: 3-57. .

- Frankenberg, W. 1912. Evagrius Ponticus. Berlin. .

- Gignac, F. T. 1976-. A Grammar of the Greek papyri of the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Milan. .

- Gignoux, P. 1987. Incantations magiques syriaques. Louvain. .

- Hamilton, V. P. 1971. Syriac incantation bowls. Ph.D. Diss., Brandeis University. .

- Hetzron, R. 1977. “Innovations in the Semitic Numeral System,” JSS 22: 167-201. .

- Huehnergard, J. 2012. An Introduction to Ugaritic. Peabody, MA. .

- Jones, F. S. 1998. “Early Syriac Pointing in and behind British Museum Additional Manuscript 12,150,” in R. Lavenant, S.J. (ed.), Symposium Syriacum VII (Orientalia Christiana Analecta 256). Rome. 429-444. .

- Joüon, P. and T. Muraoka. 1991. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Rome. .

- Kaufman, S. A. 1974. Akkadian Influences on Aramaic. Chicago. .

- Kiraz, G. A. 2012. Tūrrāṣ Mamllā. A Grammar of the Syriac Language. Piscataway. .

- Layton, S. C. 1990. Archaic Features of Canaanite Personal Names in the Hebrew Bible. Atlanta. .

- Liddell, H. and R. Scott (revised by H. Stuart Jones and R. McKenzie). 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford. .

- Look, A. E. 1929. The History of Abba Marcus of Mount Tharmaka. Oxford. .

- Loopstra, J. Forthcoming. An East Syrian Manuscript of the Syriac ‘Masora’ to 899 CE. Piscataway. .

- Macomber, W. F. 1974. Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts by Cyrus of Edessa (CSCO 355-336). Louvain. .

- Mayser, M. 1970. Grammatik der griechischen Papyri aus der Ptolemäerzeit, Vol. I. Laut- und Wortlehre, Part 1. Einleitung und Lautlehre (2nd ed.). Berlin. .

- Moberg, A. 1907-1913. Buch der Strahlen. Die grössere Grammatik des Barhebräus. Leipzig. .

- _______. 1922. Le Livre des splendeurs. La grande grammaire de Grégoire Barhebraeus. Lund. .

- Moriggi, M. 2004. La lingua delle coppe magiche siriache. (Quaderni di Semitistica 21). Firenze. .

- Moscati, S. et al. 1964. An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages. Wiesbaden. .

- Müller-Kessler, Ch. 1991. Grammatik des Christlich-Palästinisch- Aramäischen, Part 1. Schriftlehre, Lautlehre, Formenlehre (Texte und Studien zur Orientalistik 6). Hildesheim. .

- Muraoka, T. 2005. Classical Syriac. A Basic Grammar with a Chrestomathy. (2nd ed.; PLO ns 19). Wiesbaden. .

- Nöldeke, Th. 1904. Compendious Syriac Grammar. Translated from the second and improved German edition by James A. Crichton. Leipzig. .

- Palmer, L. R. 1934. “Prolegomena to a Grammar of the Post- Ptolemaic Papyri,” JTS 35: 170-175. .

- _______. 1945. A Grammar of the Post-Ptolemaic Papyri. London. .

- Pardee, D. 2003/2004. Review of Tropper 2000 (online version). AfO 50. .

- Rosenthal, F. 1995. A Grammar of Biblical Aramaic (PLO ns 5). Wiesbaden. .

- Salvesen, A. 1997. “Hexaplaric Readings in Išoʿdad of Merv’s Commentary on Genesis,” in J. Frishman and L. Van Rompay (eds.), The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation (Traditio Exegetica Graeca 5). Louvain. 229-252. .

- Scher, A. 1907. Mar Barḥadbšabba ʿArbaya. Évêque de Ḥalwan (VIe siècle). Cause de la fondation des écoles (PO 4.4). Paris. .

- Segal, J. B. 1953. The Diacritical Point and the Accents in Syriac (London Oriental Series 2). London. .

- Sokoloff, M. 2009. A Syriac Lexicon. A Translation from the Latin, Correction, Expansion, and Update of C. Brockelmann’s Lexicon Syriacum. Winona Lake – Piscataway. .

- Tropper, J. 2000. Ugaritische Grammatik. Münster. .

- Van Rompay, L. 1990. “Some Remarks on the Language of Syriac Incantation Texts,” in R. Lavenant, S.J. (ed.), V Symposium Syriacum 1988 (Orientalia Christiania Analecta 236). Rome. 269- 281. .

- _______. 2015. “L’histoire du Couvent des Syriens (Wadi al-Natrun, Égypte), à la lumière des colophons de la Bibliothèque nationale de France,” in F. Briquel Chatonnet and M. Debié (eds.), Manuscripta Syriaca. Des sources de première main (Cahiers d’études syriaques). Paris. .

- Welles, C. B., R. O. Fink, and J. F. Gilliam. 1959. The Excavations at Dura-Europus. Final Report V, Part 1. The Parchments and Papyri. New Haven. .

- Wesselius, J. W. 1991. “New Syriac magical texts,” BiOr48: 705- 16. .

- Woodard, R. D. 2004. “Attic Greek,” in R. D. Woodard (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages. Cambridge. 614-649. .

- Wright, W. 1890.Lectures on the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages. Cambridge. .

Footnotes

* I would like to thank George A. Kiraz (Beth Mardutho: Syriac Institute) for discussing this paper with me as well as for adding several examples to those cited here. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer(s) at Hugoye who provided useful feedback. Finally, I am especially grateful to Lucas Van Rompay (Duke University) for his helpful comments. Note the following abbreviation: CAD = The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (Chicago, 1956-).

1 1 Brockelmann 1981: §11; Duval 1881: §66; Kiraz 2012: §225-234; Nöldeke 1904: §16; Segal 1953: 5. For the history of the term syāmē along with alternative designations, such as nāqzay saggiyānutā ‘points of plurality’, see Kiraz 2012: §225.

2 2 As an aside, it should be pointed out that the k n Syriac ܡ̈ܠܟܐ /malkē/ ‘kings’ is not fricativized in contrast to earlier forms of Aramaic where it is, as is reflected in Biblical Aramaicmalkin‘kings’ (Ezra 4:20) *malakīn (see Rosenthal 1995: §51). This is due to an analogical development in Syriac whereby the plural base *malak- was replaced by the singular base *malk-.

3 3 A color image of this manuscript is available in Brock, Butts, Kiraz, and Van Rompay 2011: 457, where one can see several examples of syāmē marking plurality, e.g., ܣܓܝܐ̈ܐ /saggiʾē/ ‘much’ (col. 3, ln. 1). Jones (1998) has argued that many of the diacritical points after f. 40v of ms. Brit. Libr. Add. 12,150 were added secondarily; this does not, however, includesyāmēthe use of which belongs to the original scribe (see at p. 439).

4 4 Jones 1998: 435; Kiraz 2012: §2012.

5 5 In each of these examples, the singular is assured by the context – or, it is at the very least highly likely. It is tempting to add to this list τιμή (Liddell and Scott 1996: 1793-1794) > ܛܝܡܐ ‘price’ (Sokoloff 2009: 527), which is often written ܛܝ̈ܡܐ with syāmē. When written with syāmē, however, this word always seems to take plural agreement. Thus, ܛܝ̈ܡܐ is better analyzed as plurale tantum, probably on analogy to the semantically similar ܕܡܝ̈ܐ 'price’ (Sokoloff 2009: 309), which is also plurale tantum. It should be noted that the latter may well be a loanword from Akkadian damē ‘blood money’ (CAD D 79, sub2b), even though it is not included in Kaufman 1974, especially since the Akkadian form is also plural. For the association between ܛܝܡ̈ܐ and ܕܡܝ̈ܐ, see already Nöldeke 1904: §88 and Brock 1967: 422.

6 6 The singular is assured by the following adjective that does not have syāmē as well as by the witnesses of other manuscripts that have ܕܝܬܩܐ without syāmē, such as ms. Sachau 222 (1881 CE; ed. Bedjan 1890-1897: 3.272.21).

7 7 See also 94.14, 20; 146.20; 147.30; 162.21; 172.4.

8 8 See also 90.3; 150.26; 168.24; 171.13. Perhaps also ܕܐܚܕܘ ܢܘ̈ܡܐ ܠܘܬܢ ܒܥܠܬ ܕܚܡܬ ܢܝ̈ܚܐ because of the love of pleasures that spread among us’ (Isḥaq of Nineveh, Part 3, 104.16; ed. Chialà 2011). The form ܢܘ̈ܡܐ may be singular in this case, since √ʾḥd‘to take’ plus ܢܘ̈ܡܐ ‘pasture’ forms a common idiom ‘to spread’ (Sokoloff 2009: 900). It is, however, possible that ܢܘ̈ܡܐ is plural in this example due to attraction to the plural verb. Regardless, the editor’s emendation (Chialà 2011: 104 n. 38) to ܢܘ̈ܡܐ without syāmē should be rejected.

9 9 See also 160.1; 162.7; 164.1; 165.8, 18; 187.20.

10 10 Becker (2006: 104-105 with n. 79 [on p. 243]; see also 2010: 93 n. 10) suggests that the phonological use of syāmē occurs in the title of the Cause of the Foundation of the Schools: ܥܠܬܐ ܕܣܝܡ ܡܘܬܒܐ ܕܐܣܟ̈ܘܠܐ ed. Scher 1907: 13), which he would render The Cause of the Establishment of the Session of the School. It should be noted that one manuscript reads ܐܣܟܘܠܐ instead of ܐܣܟ̈ܘܠܐ, which lends support to this argument; the title at the end of the text, however, has the plural ܐܣܟܘܠܣ Scher 1907: 83.4; note, however, the lack of syāmē), which weakens the argument.

11 11 The plural of this loanword only seems to be attested as ܗܘܠܣ̈ (Sokoloff 2009: 335, 341).

12 12 The plural cannot be absolutely ruled out in the context, even if the singular seems much more likely.

13 13 Though many of these examples occur in Qiyore of Edessa’s Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts, Feasts, the phenomenon is certainly not limited to this text.

14 14 See also ܢܝ̈ܢܘܐ ‘Nineveh’, possibly due to Greek Νινευή, in ms. Paris, Bibl. Nat. 56, f. 191v (ed. Van Rompay 2015).

15 15 Allen 1987: 69-75; Woodard 2004: 617.

16 16 Allen 1987: 74-75; Gignac 1976-: 1.235-242; Mayser 1970: 46-54; Palmer 1934: 170; 1945: 1.

17 17 See Welles, Fink, and Gilliam 1959: 47 as well as the following spellings from the P.Euph. documents: ἠ for εἰ (P. Euph. 11.24 [232]); καθαροποιήσει for καθαροποιήσῃ (P.Euph. 8.27 [251]); ὑστερέσει for ὑστερήσῃ (P.Euph. 16.A.5 [after 239]). It should be noted that ε, which was a long close-mid front /e:/ in Attic Greek, had merged with ι as a high unrounded short /i/ by the Koinē Greek of the Roman and Byzantine periods (Allen 1987: 70; Gignac 1976-: 1.189-191, 235-262; Mayser 1970: 54-65; Palmer 1934: 170; 1945: 1). For this merger in the Greek of Syria and Mesopotamia, see Welles, Fink, and Gilliam 1959: 47; many additional spellings attesting this merger will also be found in the P.Euph. documents. The Greek P.Euph. documents are edited in Feissel and Gascou 1989; 1995; 2000; Feissel, Gascou, and Teixidor 1997. Images of these texts are available online at http://www.papyrologie.paris-sorbonne.fr/menu1/ collections/pgrec/peuphrate.htm

18 18 The present author is currently completing a study that uses Greek loanwords in Syriac as a witness to the Greek of Late Antique Syria and

19 19 Allen 1987: 79; Gignac 1976-: 1.191-193; Mayser 1970: 83-87. For this merger in the Greek of Syria and Mesopotamia, see Welles, Fink, and Gilliam 1959: 47 as well as the following selected spellings from the P.Euph. documents: αἰωνημένης for ἐωνημένης (P.Euph. 6.17 [249]; 7.10 [249]); ἀναπέμψε for ἀναπέμψαι (P.Euph. 4.14 [252-256]); ἀσπάζομε for ἀσπάζομαι (P.Euph. 16.A.2 [after 239]); ἐνκαλοῦμε for ἐγκαλοῦμαι (P.Euph. 3.12 [252-256]; 4.12 [252-256]); εὔχομε for εὔχομαι (P.Euph. 16.B.7 [after 239]; P.Euph. 17.2 [mid-3rd]); κελεῦσε for κελεῦσαι (P.Euph. 2.15 [mid-3rd]); ται for τε (P.Euph. 9.27 [252]); ὑπόκειτε for ὑπόκειται (P.Euph. 2.14-15 [mid-3rd]); χέρειν for χαίρειν (P. Euph. 11.11 [232]).

20 (P.Euph. 2.14-15 [mid-3rd]); χέρειν for χαίρειν (P. Euph. 11.11 [232]). 20 For this anonymous tract, see Segal 1953: 79. For a facsimile edition of the entire manuscript, see Loopstra Forthcoming. I would like to thank Jonathan Loopstra (Capital University) for sharing his work with me prior to its publication.

21 21 Translating Greek μὴ φοβοῦ Παῦλε ‘Do not be afraid, Paul’. It should be noted that both Segal (1953: 99 n. 1) and Kiraz (2012: §303) cite the folio as 303v.

22 22 The same five points appear with this letter in the version of this verse found on f. 275v, ln. 1 of Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138, which is not from the anonymous tract (303v-308v) but from the actual biblical samples.

23 23 .Segal (1953: 98-99), for instance, cites half a dozen.

24 24 The Syriac is edited in Moberg 1922: 166.16-22, and a German translation is available in Moberg 1907-1913: 1.145. It should be noted that Bar ʿEbroyo does not call these vocatives but diminutives (zuʿʿārā).

25 25 The edition has ܕܡܐ here with a single dālat; this is not impossible, though it is preferable to emend as above.

26 26 If the anonymous tract on accents (303v-308v) is older than the biblical samples in Brit. Libr. Add. 12,138, as Segal (1953: 7) supposes, then this date can be pushed even earlier.

27 27 Perhaps, the forms ending in ptāḥā are the result of West-Syriac influence, where the vocative of Greek personal names in -as end in ptāḥā.

28 28 It is from here, of course, that this analysis made its way into Segal 1953: 99 and more recently Kiraz 2012: §303.

29 29 Brockelmann 1981: §157; Coakley 2002: 134; Muraoka 2005: §44; Nöldeke 1904: §148.

30 30 So already Nöldeke 1904: §16 and Hetzron 1977: 186 n. 1.

31 31 This is certain since the same ending is found with these forms in Biblical Hebrew, which does not of course have the Aramaic masculine plural status emphaticus ending -ē, e.g., šlōš ʿeśrē ‘thirteen (FEM)’, which is written in the consonantal script as šlš ʿśrh. The etymology of the -ē that occurs in the word for ten in feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers in Hebrew and Syriac continues to defy explanation. Traditionally, it was connected with the feminine ending *-ay (see, e.g., Brockelmann 1908: §225Bdβαα [p. 412]; 249cβ [p. 489]; 1981: §106; Cowley 1910: §80L; Joüon and Muraoka 2005: §89l, 100e; Moscati et al. 1964: §12.33 [tentatively]; Wright 1890: 138; for the wider Semitic context of the feminine ending *-ay, see the bibliography and discussion in Layton 1990: 241-249). One would, however, expect the feminine ending *-ay to be realized as -ay in both Syriac and Hebrew, based on Syriac salway ‘quail’ (Sokoloff 2009: 1012; for additional examples, see Nöldeke 1904: §83) and on Hebrew śāray (Gen. 11:30), the earlier name of Sarah. Ugaritic evidence adds further difficulties to the traditional etymology that relates the -ē in the word for ten in feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers in Hebrew and Syriac to the feminine ending *-ay In Ugaritic, the word for ten in teen cardinal numbers is written as ʿšrh alongside ʿšr and ʿšrt (Tropper 2000: §62.2). Given that the word for ten is also written with final -h in the feminine of these forms in Hebrew, it is likely that Ugaritic ʿšrh is cognate to the Hebrew forms as well as to the Syriac forms, where the mater lectionis will have been changed from h to ʾ (for this change in Syriac, compare the orthography of the feminine singular status absolutus ending, which is consistently -ʾ in Syriac but was -h in Old Aramaic [Degen 1969: §34] with Biblical Aramaic attesting both forms [Rosenthal 1995: §42]). The -h in Ugaritic ʿšrh cannot be a reflex of the feminine ending *-ay because: 1. the feminine ending *-ay is probably realized as -y in Ugaritic (Tropper 2000: §52.4 with the comments in Pardee 2003/2004: 176-177); 2. Ugaritic h never functions as a mater lectionis and is always consonantal in Ugaritic (Tropper 2000: §21.342.2; Huehnergard 2012: 21). Thus, while the analysis of the final -h in Ugaritic ʿšrh remains uncertain (Bordreuil and Pardee 2009: 36; Huehnergard 2012: 49; see the discussion in Tropper 2000: §62.201), the Ugaritic evidence casts further doubt on analyzing the ending -ē on the word for ten in feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers in Biblical Hebrew and Syriac as the feminine ending *-ay (contra Joüon and Muraoka 2005: §100e, who doubt whether the Ugaritic evidence can be used to show that h in Hebrew ʿšrh was originally consonantal). It should be noted here in passing that Hetzron (1977) has proposed that the final -ē in these Hebrew and Syriac forms is – at least partially – the result of language contact with Akkadian. This is, however, unlikely given what is known about the contact between these languages as well as about contact-induced change more broadly.

32 32 The result of such an extension can be illustrated by Christian Palestinian Aramaic, where syāmē are used with masculine and feminine forms of the teen cardinal numbers as well as with many other forms of the numbers (for the forms, see Müller-Kessler 1991: §4.3.1).

33 33 Syriac incantation bowls, also called ‘magic bowls’, are earthenware bowls that are inscribed with incantations in ink. The bowls are typically thought to stem from the late Sasanian period (sixth to seventh century), though both earlier and later dates have been suggested. Two scripts are attested in the Syriac bowls: Esṭrangela and a related script that is often termed ‘Proto-Manichaean’. The language of the Syriac bowls differs in a number of ways from Classical Syriac (Van Rompay 1990). Collections of Syriac incantation bowls are available in Hamilton 1971: 98-164 as well as more recently Moriggi 2004: 235-294 (for the history of publication of Syriac bowls, see Moriggi 2004: 1-6, 47-48 with further references). The Syriac incantation bowls have parallels in Mandaic and Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.

34 34 This feature is not mentioned in Hamilton 1971: 48-49 or Moriggi 2004. In addition, syāmē are unfortunately not marked in the texts in the appendix of Moriggi 2004, leaving this interesting difference between Classical Syriac and the language of the Syriac incantation bowls indiscernible to the reader (syāmē are marked in Hamilton’s texts, even though they are written in square script).

35 35 For this edition, see the review article in Wesselius 1991.

36 36 This use was, however, noted by Van Rompay (apud Salvesen 1997: 245 n. 66), Becker (2010: 93 n. 10), and Kiraz (2012: §158).

37 37 Following a similar development, syāmē occasionally function as a phonological marker for a final mid front vowel in Christian Sogdian texts (Sims-Williams, apud Kiraz 2012: §621).