The Fourfold Gospel in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian

Ephrem of Nisibis is unique among patristic authors for having authored a commentary on Tatian’s gospel commonly known as the “Diatessaron.” In this article I examine Ephrem’s corpus to determine what evidence exists for his knowledge and use of gospel versions beyond that of Tatian, most especially the fourfold, or separated gospel. I point out that Ephrem, in keeping with Greek and Latin authors, occasionally used poetic imagery for the fourfold gospel, and, moreover, that he knew at least the Synoptic genealogies and the Johannine prologue as distinct texts. It is undeniable, therefore, that he knew of and to some degree used the separated, fourfold gospel, even if this remained slight in comparison with his reliance upon Tatian’s version. Furthermore, on six occasions Ephrem refers to an unspecified “Greek” gospel version. Previous scholarship has almost universally interpreted these passages as references to a separated gospel in Syriac, but I argue that these are best taken as references to an actual Greek version, and may well be allusions to a Greek edition of Tatian’s work. Ephrem’s usage of multiple gospel versions suggests that at this point in the Syriac tradition, the concept of ‘gospel’ was fluid and more undefined than would be the case in the fifth century when attempts were made to restrict its sense to the fourfold gospel.

In the words of the late William Petersen, the fourth-century commentary of Ephrem the Syrian “remains the premier witness to the text of the Diatessaron. 1 Moreover, Ephrem’s commentary occupies a unique place in early Christianity as the only surviving commentary on a gospel text other than the usual, fourfold gospel 2 Indeed, although he was, according to the report of Sozomen the historian, greatly admired by Greek-speaking Christians such as Basil of Caesarea and although he, like Basil, opposed the Arians 3 his commentary on the gospel text created by the second-century heretic Tatian causes him to stand out sharply against the backdrop of other fourth-century authors for whom the tetraevangelium was the unquestioned standard. Undoubtedly Ephrem’s usage of this peculiar gospel text is related to the fact that he wrote in Syriac and lived on the border of the Roman Empire, spending most of his life in Nisibis, before fleeing to Edessa when the Romans ceded the city to the Persians after Julian’s disastrous eastern campaign.

Thus, Ephrem’s composition of a commentary on Tatian’s gospel could be taken as an indication that he stands apart from the Greek patristic tradition, inhabiting a Syriac world as it existed prior to the time when the Greek church imposed itself upon what has been called a “genuinely Asian Christianity. 4 Indeed, in the opinion of Sebastian Brock, Ephrem’s significance lies precisely in the fact that he belongs to a version of Christianity that “was as yet comparatively little touched by [the] process of hellenization, or as we may call it, Europeanization or Westernization. 5 On this reading, we should not be surprised if Ephrem used a gospel text quite unlike that current in Greek churches, since his contact with the Greek world was minimal at best.

pb. 11However, this picture of Ephrem as untouched by the forces of Hellenization has recently been subjected to significant critique in the work of Ute Possekel. Through a careful reading of the Syrian’s corpus, Possekel has demonstrated beyond any doubt that Ephrem was actually well versed in the philosophical milieu that broadly characterized the late antique Mediterranean world, and that he had a particular affinity for Stoic philosophy 6 As such, he can hardly be said to be ‘un-Hellenized.’ This clear evidence of Ephrem’s knowledge of Greek philosophical sources forces us to reconsider his idiosyncratic usage of Tatian’s gospel. If the Syriac culture of Nisibis and Edessa had absorbed Hellenistic philosophy by at least the mid-fourth century, it is unlikely that the version of Christianity that existed in those places remained untouched by Greek Christian sources.

To be clear, there is good reason to think that churches in Syriac-speaking areas were peculiar in their usage of Tatian’s gospel. While there is slim evidence that Tatian’s work circulated widely in the Greek world, it was quite possibly the earliest version in which the written gospel reached the Syriac world, and it enjoyed a primacy in some areas until the first half of the fifth century 7 However, given the interaction between Greek and Syriac sources apparent in Ephrem’s writings, we should expect that his knowledge of gospel texts presents a similarly mixed picture. Hence, in what follows, I intend to investigate Ephrem’s corpus in search of evidence that he knew and availed himself of not only the Syriac version of Tatian’s gospel, but also the fourfold, or separated gospel.

I wish to argue that, although Tatian’s work remained the standard gospel version for Ephrem and his community, he nevertheless was aware of the existence of the fourfold gospel, and, moreover, he knew the Matthean and Lukan genealogies and the Johannine prologue as distinct texts linked with their respect evangelists. A handful of other passages in his corpus which display pb. 12 a greater knowledge of evangelist traditions are likely later interpolations and so do not reflect Ephrem’s own knowledge. Furthermore, I suggest that Ephrem’s allusions to “the Greek” gospel, although almost universally taken by previous scholarship as references to a separated, Syriac gospel, are best understood as allusions to an actual Greek version, and possibly to a Greek edition of Tatian’s work. This picture of Ephrem making use of a range of gospel literature is in keeping with Possekel’s argument that he had a foot in both the Syriac and Greek worlds. Moreover, it suggests that he occupied a transitional moment in the cross- fertilization of Greek and Syriac Christianity. His willingness to continue using Tatian’s gospel despite his awareness of the fourfold gospel contrasts sharply with the attitude displayed two generations later by Theodoret and Rabbula who insisted that only the fourfold gospel in Syriac translation be used in the churches under their care. To this degree Brock’s interpretation of Ephrem is correct, since the Syriac milieu in which he wrote apparently tolerated a greater diversity than would be the case in the following century.

One way to approach this topic would be to compare the gospel texts cited by Ephrem with the Vetus Syra or with the Peshitta to see if they correspond to either of the earliest known Syriac versions of the separated gospel. This was the method followed by F. C. Burkitt one hundred years ago, who concluded that Ephrem certainly did not use the Peshitta, and more often than not used Tatian’s version rather than the Vetus Syra 8 However, positive evidence that the Syrian usually used Tatian’s gospel does not exclude the possibility that he also knew and availed himself of other gospel versions. Therefore, I intend to take a different approach, considering three different lines of inquiry: first, the imagery for the fourfold gospel that occurs in Ephrem’s corpus; second, Ephrem’s awareness of individual evangelists; and third, what to make of the references in his corpus to “the Greek” version. As will become clear in what follows, many of the passages I will consider have been examined previously by Burkitt and pb. 13 several others. However, several important passages have been overlooked in these prior discussions, and even those passages which have previously received some attention merit further scrutiny. Hence, I intend to provide the most thorough consideration thus far of the evidence for Ephrem’s knowledge of the fourfold gospel.

1. IMAGERY FOR THE FOURFOLD GOSPEL IN EPHREM’S CORPUS

Metaphorical imagery occupied a central place in Irenaeus’ famous defense of the fourfold gospel, and such imagery became a widespread and consistent feature of the Christian tradition, whether in its Greek, Latin, or Syriac forms. Ephrem, who was chiefly remembered for his poetic insight, also used such imagery, though only in a very small number of passages. Three are particularly relevant.

The first passage occurs in his Hymns on Faith 48.10. Here, at the end of this hymn, Ephrem writes, The Gospel pours forth (ܓܚܬ) in the type of the Gihon (ܓܝܚܘܢ) to give water. By the Euphrates (ܒܦܪܬ) its fruit (ܦܪܝܗ) is represented because it multiplied its teaching. He depicts its type by the Pishon (ܒܦܝܫܘܢ) and the cessation (ܘܦܘܫܗ) (of its investigation. It cleans us (ܕܩܠܬܢ) like the Tigris (ܕܩܠܬ) (by its speech. We will bathe and we will ascend through it to the encounter in Paradise . . 9 Other early Christian authors, such as Hippolytus, Cyprian, Victorinus of Petovium and Jerome used the four rivers of paradise as a metaphor for the fourfold gospel 10 so it is not without warrant pb. 14 that Louis Leloir and Christian Lange have taken this passage as a reference to the four gospels 11 However, a closer examination suggests that, while this interpretation of the passage is possible, it is not required. First of all, we should note that the word translated here as “Gospel” is not ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ but rather ܣܒܪܬܐ .%$#Though the two terms have obviously overlapping semantic domains, the former is clearly transliterated from Greek whereas the latter is a native Syriac term. In the Peshitta New Testament these terms are used interchangeably, with no discernible distinction between them, and Tj. Baarda has argued that for Aphrahat they are also synonymous 12 It is difficult to know for certain how Ephrem distinguished them, if indeed he did so at all, but it is clear that he called his gospel commentary an exposition of the ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ and not the ܣܒܪܬܐ 13 Hence, it is possible that ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ in his usage refers to his written text while ܣܒܪܬܐ is associated more generally with the proclamation of the good news, in which case we need not read the above passage as a reference to the fourfold gospel. Furthermore, there is certainly a poetic play on words going on in this passage, since each of the names of the four rivers sounds similar to the four qualities of the gospel mentioned in each line. 14 Thus, the imagery of the four rivers may simply serve the purpose of this poetic device, being used to illustrate the manifold effect of pb. 15 gospel proclamation, rather than standing as an allusion to its fourfold written form.

The next two passages much more clearly demonstrate an awareness of the gospel in its fourfold form. Lange has drawn attention to Ephrem’s Sermons on Faith 2.39-40, in which the Syrian says, “Four fountains (ܐܪ̈ܒܥܐ ܡܒ̈ܘܥܝܢ) (flow down with truth for the four regions of the world.” Just prior to this sentence he speaks of the “former fountains” which are “sufficient,” and in what follows he refers to the revelation given to Simon Peter. He then tells his hearers that the “mighty stream” which came to Simon flowed also to them, a torrent that is even greater than the “fount of Eden. 15 Ephrem’s intent in this paragraph seems to be to exhort his hearers to be content with what Scripture says as they contemplate the divine, rather than attempting to pry into matters that remain hidden to human knowledge. In light of the reference to Peter, the “former fountains” presumably refers to the divine revelation given to the apostles, which Ephrem’s opponents transgress by attempting to provide an explanation for the Son’s generation. The “four fountains” then, is likely a reference to the four gospels which preserve the apostolic witness to the revelation of Christ. Furthermore, Ephrem’s cosmological notion that the four gospels correspond to the four regions of the world was a point first made by Irenaeus and then picked up by a number of later Greek and Latin authors 16 so in this respect his understanding of the fourfold gospel was in keeping with the wider Christian tradition.

The final passage is even more telling than the previous three. In his Hymns on Virginity 51.2, Ephrem once again poetically interweaves imagery from creation with the themes of Scripture and revelation. This time he notes that, just as the sun shone forth in every place on the fourth day of creation, so also “our sun shone forth in four books” (ܒܐܪܒܥܐ ܣܦܪ̈ܝܢ ܐܙܠܓ ܠܗ ܗܘ ܫܡܫܢ).17 17 pb. 16 There can be little doubt that the “four books” mentioned here are the four canonical gospels, from which the light of the gospel has gone forth into the earth. Moreover, the geographic spread of the gospel to the four regions mentioned above in the Sermons on Faith is also evident here in the metaphor of the sun that shines upon all creation.

These references to the fourfold gospel are few in Ephrem’s corpus, but they do demonstrate that he was at least aware of the tetraevangelium, though they leave open the question of to what extent he actually used it. It is notable that in the unambiguous reference to the fourfold gospel in the Sermons on Faith he is particularly concerned with emphasizing the authoritative tradition handed down from the apostles, which they had received from Christ. The same intent is possibly also implicit in the latter passage from the Hymns on Virginity. In other words, he does not speak of the fourfold gospel as though it were the text regularly used by him and his community, but rather as the original deposit of revelation given by Christ to his followers. It is also striking that in these passages he demonstrates no attempt to state the relationship between the fourfold gospel and Tatian’s gospel upon which he authored a commentary, nor does he betray any sense that these gospel versions should be opposed one to another.

Moreover, we should also observe that Ephrem does not say there are “four gospels,” but rather “four books.” In fact, he displays a consistent pattern of speaking of the “Gospel” only in the singular. This tendency is well illustrated in his Hymns against Heresies 22.1. He begins this acrostic poem by comparing Scripture to the alphabet. As the alphabet is complete and lacks no letter, so too also is “the truth written / In the holy Gospel / With the letters of the alphabet, / A perfect measure that admits / Neither lack nor surplus. 18 The mention of truth being written indicates that here Ephrem has in mind not just generic gospel proclamation, but specifically the gospel in written form. It is therefore notable to see him refer to the gospel in the singular (ܒܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ). Thus, even though he on occasion acknowledged pb. 17 the existence of the gospel in its fourfold form, Ephrem’s idea of “gospel” retains a notion of unity that corresponds with the singular form in which he knew the gospel in Syriac.

In fact, Ephrem’s mention of “four books” corresponds to at least one other roughly contemporaneous Syriac source that is of great significance. The earliest copy of the separated gospels in Syriac, the Codex Sinaiticus Palimpsest written in the late fourth or early fifth century, calls itself the “Gospel of the Four Separated Books” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ܕܡܦܪ̈ܫܐ ܐܪ̈ܒܥܐ ܣܦܪ̈ܝܢ) 19 This parallel does not necessarily imply a direct link between Ephrem and Sinaiticus, but does suggest that the unknown Syriac scribe responsible for the manuscript inhabited a Syriac milieu similar to that of Ephrem. The scribe, who was likely accustomed to the gospel in its singular form, sought to retain the notion of singularity for the word “gospel” and preferred to speak of the plurality in terms of multiple “books.”

2. EPHREM’S KNOWLEDGE OF EVANGELIST TRADITIONS

2.1 Evangelist Traditions in the Commentary on the Gospel

We have now seen that Ephrem knew that the gospel existed in a fourfold form, but we should press further and look for clues that he knew more about these “four books” beyond their mere existence. It is, of course, possible that some of the gospel citations in his corpus actually come from the separated gospel, but since much of Tatian’s gospel presumably overlapped with the tetraevangelium, it is often difficult to determine the source of any given citation. However, information about the individual evangelists is a more sure sign that Ephrem knew something of what made each of the gospels distinct from one another.

In searching for evangelist traditions in Ephrem’s corpus, it is best to begin with his gospel commentary before extending the net more widely 20 As I have noted in a previous publication, nowhere pb. 18 in Ephrem’s gospel commentary is the title “Diatessaron” or the name “Tatian” mentioned. Instead, Ephrem gave his exposition the rather austere title Commentary on the Gospel (hereafter CGos), as can be seen from the sole surviving Syriac manuscript, Chester Beatty 709, as well as from later Syriac references to his work. This title suggests that he knew Tatian’s work as simply the “Gospel,” despite Eusebius’ report that Tatian called it the “Gospel through Four,” or “Diatessaron. 21 In keeping with this generic title, the gospel cross-references cited in the commentary are introduced on six occasions as coming from an unspecified ܐܘܢܓܠܣܛܐ (“evangelist”) 22 On two occasions the word is used to introduce a citation from the Gospel of John (CGos I.7; IX.14a), three times for the Gospel of Matthew (CGos II.1; III.9), and once for the Gospel of Luke (CGos VII.15).

As can be seen from a passage early in commentary, these citations attributed to an ܐܘܢܓܠܣܛܐ are best taken as references to the gospel text upon which Ephrem is commenting, with the result that the unspecified “evangelist” is probably the individual responsible for this united gospel text, rather than one of the four canonical authors. The Syriac gospel commented upon by Ephrem pb. 19 began with John 1:1-5 before transitioning to Luke 1:5 and the subsequent Lukan narrative about the birth of John the Baptist. Hence John 1:5 and Luke 1:5 stand on either side of a “seam” at which Tatian stitched together his source materials. As Ephrem concludes the section of his commentary on John 1:1-5 he writes,

[The evangelist] next proclaims the inauguration of the economy with the body, and begins by saying that he whom the darkness did not comprehend (Jn 1:5), nonetheless came into being in the days of Herod, king of Judea (Lk 1:5) 23

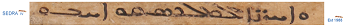

ܐܩܦ ܕܢܪܙܝܘܗܝ ܠܫܪܝܐ ܕܡܕܒܪܢܘܬܗ ܕܒܝܕ ܦܓܪܐ. ܘܫܪܝ ܕܢܐܡܪ ܕܡܢ ܕܚܫܘܟܐ ܠܐ ܐܕܪܟܗ. ܗܘܐ ܕܝܢ ܒܝܘ̈ܡܝ ܗܪܘܕܣ ܡܠܟܐ ܕܝܗܘܕܐ

Although Ephrem is surely aware that the subject matter of John 1:1-5 differs markedly from that which is taken up in Luke 1:5 and following, he seems here to attribute the authorship of both passages to the same individual, likely the “evangelist” to whom he refers earlier in his exposition of John 1:5. The author who previously said the darkness did not comprehend the light “next” said that this one came to pass in the days of Herod. Therefore, this passage suggests that Ephrem’s “evangelist” mentioned several times in the commentary was the individual responsible for the text before him, rather than Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John individually.

There are, however, two passages in the commentary that seem to present a different picture. One of these is almost certainly a later interpolation though the second is possibly original. Ephrem’s commentary as it is available to us today exists in two recensions, one in Syriac and one in Armenian, and although the Armenian usually represents a close rendering of the Syriac original, there are passages which appear only in the Armenian and also some which show up only in the Syriac. As a result of this divergence in the two traditions, Christian Lange has argued that interpolations occurred pb. 20 in both recensions 24 One such passage that occurs only in the Syriac version is the second half of CGos I.26, a paragraph that evinces a greater knowledge of the individual evangelists than is evident from the other unspecified references to the “evangelist.” This paragraph occurs in the midst of Ephrem’s exegesis of the annunciation to Mary, and Mary’s subsequent visit with Elizabeth. Here Ephrem is primarily concerned with emphasizing Mary’s descent from the tribe of Judah, rather than from the tribe of Levi, despite the fact that Elizabeth, who was presumably a Levite, was called her kinswoman (Luke 1:36). For Ephrem it is essential that Mary be descended from David, and therefore from the tribe of Judah, in order for Christ to be the heir of the promises given to David. He makes this point by arguing on the basis of Luke 2:4, which in his version states that both Mary and Joseph were from the house of David (CGos I.25) 25 He next cites a string of cross- references all of which mention Jesus’ Davidic lineage (Luke 1:32; Isa 11:1; Luke 1:69; 3 Cor 5; 2 Tim 2:8), and then suggests that the tribes of Levi and Judah had mixed through the marriage of Aaron and the sister of Nahshon (cf. Exod 6:23) (CGos I.26) 26

Thus, Jesus’ Davidic lineage is established and Mary’s kinship to Elizabeth is explained. Having sufficiently made his point, Ephrem’s exposition seems to be complete. However, the Syriac text subsequently launches into a new discussion regarding the genealogies of Matthew and Luke, in which both authors are named, with Luke even being called “Luke the evangelist” (ܠܘܩܐ ܐܘܢܓܠܣܛܐ) 27 The apparent intention of this paragraph is pb. 21 to reconcile the two discordant genealogies in the canonical gospels (CGos I.26), a concern that did not feature at all in the previous section. The solution proffered is that Matthew wrote regarding Mary’s descent and Luke about that of Joseph 28

If authentic, this passage would serve as indisputable evidence that Ephrem knew at least some traditions from the separated gospels, both because Ephrem explicitly names Matthew and Luke, and because it is known from Theodoret’s report that Tatian’s gospel omitted the genealogies 29 However, there is reason to think otherwise. As noted above, this passage does not occur in the Armenian recension 30 which immediately casts a shadow of suspicion upon its authenticity, a suspicion that is strengthened by the fact that the additional material is internally incoherent with the surrounding context. In the midst of the prior discussion in CGos I.25, Ephrem states that Scripture reckons genealogies ܫܪ̈ܒܬܐ pb. 22 through male descent, and “is silent” ܫܬܩ about the genealogies of women 31 This same point, that Scripture accounts genealogies through men rather than women, is also made by Ephrem in his Hymns on the Nativity 2.13, where he again notes that both Mary and Joseph were of Davidic descent 32 It is difficult to see how to reconcile this clearly Ephremic idea with the additional material at CGos I.26, which states explicitly that “Matthew wrote concerning the geneaology of Mary (ܡܬܝ ܕܝܢ ܫܪܒܬܗ̇ ܗܘ ܕܡܪܝܡ ܐܟܬܒ), This discrepancy suggests that the additional material is best regarded as a later interpolation made sometime following the division of the manuscript tradition into the two recensions available today. As such, it tells us nothing about Ephrem’s own knowledge of gospel traditions. Given the age of the Syriac manuscript of Ephrem’s commentary (late fifth or early sixth century), this addition provides further evidence alongside Theodoret’s report that some in the fifth-century Syriac-speaking communitiy were troubled by the genealogies of Jesus, whether how to reconcile them or their omission from Tatian’s gospel.

There is one further passage in the commentary which appears to indicate knowledge of individual gospel traditions. The very end of the Syriac manuscript contains a brief paragraph as a conclusion or appendix, which bears the title “The Evangelists” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝ̈ܣܛܐ), and which offers an explanation as to why there are four gospels. The author of this short section acknowledges that “the words of the apostles are not in agreement” (ܕܠܐ ܕܝܢ ܫܠܡܢ ܡ̈ܠܝܗܘܢ ܕܫܠܝ̈ܚܐ), but explains this discrepancy by noting that they did not write “the Gospel” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ) at the same time, since, unlike the giving of the tablets to Moses, they each wrote by the Spirit under various circumstances (cf. Jer. 31:31-33). In what follows the author of this paragraph gives a brief recounting of the origins of the gospels: Matthew is said to have written in Hebrew which others later translated into Greek; Mark followed Peter and wrote from Rome after the faithful persuaded him to take up the task; Luke began his account with the “baptism of John;” and finally John, finding that Matthew and Luke had spoken of the “genealogies [showing] that pb. 23 he was the Son of Man” (ܫܪ̈ܒܬܗ ܕܡܪ ܐܢܫܐ ܗܘ), ,(,+)*decided to highlight his divinity by beginning with “In the beginning was the Word. 33

If authentic, then this passage provides undeniable evidence that evangelist traditions from the Greek church had reached into Ephrem’s Syriac world. The comment about Matthew goes back to a report of Papias preserved by Eusebius 34 The description of Mark’s writing activities also draws on statements from Papias and Clement of Alexandria, though, once again, these were mediated via Eusebius 35 Furthermore, the fact that the author of this paragraph alludes to the Matthean and Lukan genealogies in order to introduce the fourth gospel likewise draws on earlier tradition. In terms of its structure, this passage is similar once again to Eusebius’ summary of Clement’s argument that the gospels with the human genealogies were written first, and that John, seeing the “bodily facts” recorded in them, decided to compose a “spiritual gospel. 36 However, despite this clear structural similarity, the way this paragraph describes the two genealogies is idiosyncratic, asserting that “one” of these evangelists spoke about Christ’s “incarnation and about his kingdom from David” while another evangelist highlighted his descent “from Abraham.” Matthew’s genealogy does indeed begin with Abraham, so this is straightforward. However, there is no obvious reason why someone would refer to the Lukan account as being “about his kingdom from David,” a description that is, as far as I am aware, without parallel. Both the Matthean and the Lukan genealogies pb. 24 include David, so the description offered is unsuccessful if it is an attempt to identify what is distinctive about Luke’s genealogy.

This final paragraph occurs in both the Syriac and in the Armenian recensions of the commentary, so we might initially be inclined to regard it as authentic. However, Lange has highlighted the fact that some interpolations occurred prior to the division of the Syriac and Armenian versions, so this observation alone is insufficient to settle the matter. The paragraph has no connection with what precedes it, nor with any other portion of the commentary, leading Leloir and McCarthy to question its authenticity 37 Furthermore, the awareness of specified “evangelists” in the plural contrasts with the singular and undefined usage elsewhere in the commentary. Moreover, the Armenian adds a further paragraph describing the journeys and missions of the apostles, which demonstrates that the end of a commentary was a prime location for later scribes to supplement the preceding discussion with traditional material 38 For these reasons it seems most likely that this paragraph is not authentic, in which case it should not be used as evidence of Ephrem’s knowledge of evangelist traditions.

Even if not authentically Ephremic, this passage does shed valuable light on Syriac Christianity. Whenever this interpolation occurred, it must have been prior to the copying of Chester Beatty 709, a fifth- or sixth-century manuscript. It was during this same period that Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History was making itself known in the Syriac world, which agrees with the fact that the paragraph reveals the influence of Eusebius’ reports about gospel origins. Eusebius’ works were translated into Syriac at an early stage, possibly even within his own lifetime. The oldest Syriac manuscript, written in Edessa in 411 (BM Add. 12,150), contains several of his works, and the oldest extant witness to his Ecclesiastical History in any language is a Syriac manuscript dated to pb. 25 462 39 Eusebius is known to have had some connection with Edessene sources, given his knowledge of the Agbar legend 40 and certainly by the early fifth century at the latest this cultural transmission was going in the reverse direction as well. Whoever authored this paragraph was apparently drawing on the Ecclesiastical History to supplement Ephrem’s commentary, which probably came to appear out-of-date rather quickly once the fourfold gospel was established as the norm.

2.2 Evangelist Traditions in Ephrem’s Broader Corpus

At this point we should consider whether this pattern we have observed in Ephrem’s Commentary on the Gospel is consistent with what we find throughout his corpus. To begin with, it is important to observe that the transliterated term ܐܘܢܓܠܣܛܐ”) evangelist”), noted above as occurring on a handful of occasions in the Commentary on the Gospel, is exceedingly rare in Ephrem’s writings. Edmund Beck, who during the mid-twentieth-century provided new editions for a number of Ephrem’s works, noted that the only other occurrence of the word in Ephrem’s genuine corpus comes in his Commentary on Genesis, in which the Syrian introduces a citation of John 1:3 with the formula, “the evangelist has said.” 41 The fact that the word shows up at least once elsewhere in Ephrem’s corpus demonstrates that its occurrence in the Commentary on the Gospel cannot be used as an argument against Ephremic authorship of the gospel exposition, though certainly it presents an unusually high concentration of the term, perhaps due to the fact that it is, after all, a commentary on a gospel text. Still, pb. 26 the paucity of the term in Ephrem’s corpus is striking and speaks against it having been a common word in his Syriac milieu.

Furthermore, Ephrem’s gospel citations typically lack any attribution to a specified evangelist. In his study of Ephrem’s gospel citations Burkitt pointed out that he knew of only two passages from his corpus in which the Syrian refers to an individual evangelist 42 The first passage comes from Ephrem’s Hymns on Faith. Here he states that “John is like Moses” and “the one ‘In the beginning’ is like the other ‘In the beginning. 43 The second passage noted by Burkitt is similar, and occurs in a memra on the Johannine prologue preserved in fragmentary form by Philoxenus of Mabbug. Here Ephrem states that “John” “began with the generation of the Son (ܐܫܪܒܗ ܕܒܪܐ) from the point where [it says] ‘Through him all things were created’.” The following fragment from this homily likewise notes that when “John” said the Word was “in the beginning” he was calling in Moses as a witness 44

In addition to the naming of the evangelist John, we should also note that the version of John 1:3 cited here differs from that given elsewhere in Ephrem’s corpus. In the fragmentary memra he cites the passage in the form ܒܐܝܕܗ ܐܬܒܪܝ ܟܠ ܡܕܡ, whereas in his Commentary on the Gospel, the passage is cited as ܗܘܐ ܟܠ ܡܕܡ ܒܗ.45> 45 Since these fragments are preserved in a work by Philoxenus, we might conjecture that Philoxenus has emended Ephrem’s original citation to correspond to his own gospel version. However, it is fairly certain that Philoxenus’ version read ܒܐܝܕܗ ܗܘܐ ܟܠܡܕܡ 46 so Philoxenus was probably not responsible for the alteration. In fact, none of the Syriac versions available to us today pb. 27 have ܐܬܒܪܝ for ἐγένετο of John 1:3 47 leading Burkitt to remark, “the texts used by Ephraim in the beginning of the Fourth Gospel are thus diverse and their source is not at all clear. 48 We should also consider the possibility that the version of John 1:3 cited by Ephrem here is something less than an exact quotation. He introduces the passage by saying that John began “from where (ܡܢ ܟܪ) all things were created through him,” and notably does not use the citation marker ܠܡ. Therefore, the verb ܐܬܒܪ may be Ephrem’s own gloss on the more ambiguous ܗܘܐ of John 1:3, in which case we need not posit a distinct, now lost, Syriac version lying behind the apparent citation 49

In addition to these two references to John the evangelist, there are at least two other relevant passages that Burkitt failed to mention. The first is a brief allusion in Ephrem’s Hymns on Virginity, in which the poet does not explicitly name John the evangelist, but does identify the author of the Johannine prologue with the beloved disciple who reclined upon Jesus in the upper room (cf. John 13:23-25), implying an awareness of the fourth gospel as a distinct source 50 The second passage also refers to individual evangelists, though this time it is the synoptic gospels that are in view. At the end of the second of his Hymns on the Nativity, Ephrem notes that “Luke and Matthew traced his [i.e., Christ’s] lineage: Son pb. 28 of Abraham they reckoned him—and of David and of Joseph, so that by the learned mouths of two witnesses ... 51 This passage not only mentions the evangelists and their genealogies, but also provides a theological rationale for the existence of genealogies in two sources. In addition, in hymn nine of this series, Ephrem singles out Tamar, Rahab, and Ruth for special attention, undoubtedly because they are the only three women to appear in the Matthean genealogy 52 In the light of these passages, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Ephrem knew not only of the existence of the genealogies, but some specific details about their content. We should observe, however, that the genealogies are not viewed here as a potential problem needing to be resolved, as was the case in the already mentioned interpolation in the Commentary on the Gospel. Rather they harmoniously function together to attest to Christ’s origins.

There is yet another passage in Ephrem’s corpus also overlooked by Burkitt, also pertaining to the fourth gospel, but it is of questionable authenticity. In 1917 J. Schäfers, in his Evangelienzitate in Ephraems des Syrers Kommentar zu den paulinischen Schriften, first drew attention to a passage from an Ephesians Commentary attributed to Ephrem that survives only in Armenian 53 In the preface to the commentary, the author notes that “the Ephesians were taught by John the evangelist,” who, when he “saw that his three companions had composed their gospels (evangeliorum) from the body (a corpore)," began his own gospel with Christ’s descent not “from Mary, or from David, and from Abraham, and from Adam,” but rather “from the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. 54

This passage is largely in keeping with what we saw above in the final paragraph of the Commentary on the Gospel. It has exactly the same structure, introducing the fourth gospel by way of a contrast with the beginning of the synoptics, and, moreover, summarizing the message of the fourth gospel by way of quoting its opening lines. Furthermore, as in the previous passage, so also here the description of the synoptics is somewhat unclear. Although Mark is presumably in view as well, since the passage speaks of “three” gospels prior to John’s writing, the phrase “from Mary, or from David, and from Abraham, and from Adam” hardly serves as a description for the Markan gospel, since it includes no infancy narrative. Furthermore, it is not even clear what in this passage serves to refer to Matthew and Luke. Neither include Mary in their genealogies of Jesus, though both include David and Abraham, and only Luke includes Adam (Matt 1:1-18; Luke 3:23-38). Thus, although we can say with certainty that this passage draws upon the same Clementine-Eusebian tradition that contrasted the genealogies of Matthew and Luke with the opening of John, it appears that again the information has somehow become confused in transmission, just as in the final paragraph of the Commentary on the Gospel 55

If the final paragraph of the Commentary on the Gospel is an interpolation, as I have argued, then this implies we should be skeptical of this section as well in light of the parallels between the pb. 30 two. The Pauline commentaries attributed to Ephrem survive only in Armenian and have been very little studied, while it is known that much spurious material survived under Ephrem’s name, especially in Armenian 56 Finally, Lange has argued that in at least one instance the commentary provides an interpretation that differs from the “authentic Ephrem,” and he therefore advocates keeping open the question of its authenticity pending further study 57 I suggest, then, that we not view this passage as evidence of Ephrem’s knowledge of evangelist traditions.

Excluding the final paragraph of the Commentary on the Gospel and the short passage from the Pauline commentaries, there is no clear evidence that Ephrem knew the otherwise common evangelist traditions explaining the origins of the four gospels. Moreover, the only specific passages we can be sure that he knew from the separated gospels are the Matthean and Lukan genealogies and the Johannine prologue. In one sense this is not too surprising since these texts had long been the twin pillars for understanding the nature of Christ, going back to Irenaeus who first stated that Matthew told of Jesus’ “generation as a man” and John his “generation from the Father. 58 As noted above, Clement passed on a version of this tradition as well, contrasting the Synoptic genealogies with the opening of the fourth gospel. The fact that Tatian’s edition excluded the genealogies would make have made these passages from the fourfold gospel stand out prominently to Ephrem. The genealogies might, then, have been viewed as a sort of supplement to his usual gospel text. Moreover, the Johannine pb. 31 prologue is perhaps the most unique passage in all four canonical gospels, and was notably important in the ‘Arian’ controversy of the fourth century, in which Ephrem took part 59 so it is to be expected that this passage would particularly draw his attention. In other words, even if Ephrem did not necessarily know the Eusebian evangelist traditions, he seemingly shared with his Greek and Latin contemporaries the conviction that the Synoptic genealogies and the Johannine opening were unique and important passages 60

3. EPHREM AND “THE GREEK”

In light of the material considered thus far, it is clear that Ephrem knew of the existence of the four gospels, knew that the opening of the fourth gospel was written by the evangelist John, and knew the Matthean and Lukan genealogies in some detail. These observations leave little doubt that he worked with some version of the separated gospels alongside his unified gospel text. We should now consider whether there are any explicit references in his corpus to distinct gospel versions aside from the sort of unspecified references to the “gospel” that remain difficult to identify. The only such passages are a half-dozen instances in which he provides variant readings that he says derive from “the Greek Gospel” or simply “the Greek.” One of these references occurs in his Refutationes ad Hypatium and a further five show up in the Commentary on the Gospel, both texts that are usually dated during the final decade of Ephrem’s life that he spent in Edessa.

pb. 32 Since it has been traditionally assumed that Ephrem did not know Greek, Burkitt and Arthur Vööbus suggested that Ephrem refers in these passages to a Syriac translation of the fourfold gospel which he calls “the Greek” to distinguish it from Tatian’s version, which was more well known among Syriac speakers 61 In other words, Burkitt and Vööbus argued that by calling this version the “Greek” Ephrem was referring not to its language of composition, but to the form in which this gospel existed. Leloir was more cautious, preferring instead to suppose that Ephrem had access to a number of individual variant readings from the Greek separated gospels 62 Lange, also assuming that these represent a separated, Syriac translation, has most recently surveyed these passages in an attempt to determine what version of gospel text lies behind the citations, but he was unable to clearly identify the passages with either the Vetus Syra or the Peshitta 63 In what follows I intend to consider each of these passages closely to determine if they indicate usage of the fourfold, separated gospel, as has often been supposed.

In the passage from the Refutationes ad Hypatium, the Syrian opposes an interpretation of John 1:4 offered by the Manicheans. He begins by saying that the passage “in the Gospel” (ܒܐܢܓܠܝܘܢ) reads “the life is the light of a man” (ܕܐܢܫܐ ܕܗܢܘܢ ܚܝ̈ܐ ܐܝܬܝܗܘܢ ܢܘܗܪܐ). .(Apparently the Manicheans draw from the singular “man” the conclusion that the passage speaks of the “primal man” (ܩܕܡܝܐ ܐܢܫܐ) who plays a role in Manichean cosmology. Against this exegesis Ephrem brings the reading from “the Greek Gospel” pb. 33 (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ܝܘܢܝܐ), which says “the life is the light of men” (ܚܝ̈ܐ ܐܝܬܝܗܘܢ ܢܘܗܪܐ ܕܒ̈ܢܝ ܐܢܫܐ ܕܗܢܘܢ) 64 As David Bundy and Christian Lange have observed, the singular form ܐܢܫܐ is ambiguous in that it could be a collective singular (“humanity”) or a true singular (“a man”). This is the ambiguous reading that apparently occurred in Ephrem’s “Gospel” and that lent itself to Manichean exegesis. However, the plural rendering ܒ̈ܢܝ ܐܢܫܐ derived from “the Greek gospel,” removes the ambiguity by explaining the singular as a collective singular, ruling out any reference to the primal man 65

It is curious then that, in the only citation of John 1:4 in the Commentary on the Gospel, the reading given is ܒ̈ܢܝ ܐܢܫܐ, which corresponds to the reading from “the Greek Gospel” rather than to that which occurs in Ephrem’s standard gospel text according to the Refutationes ad Hypatium 66 If Ephrem composed his Commentary on the Gospel after engaging in this bit of anti-Manichean polemic, then he might have revised the reading himself when commenting upon the passage in his gospel commentary in order to rule out the heretical implication. At any rate, the reading in the Greek gospel tradition is indeed τῶν ἀνθρώπων, and the Curetonian manuscript of the Old Syriac agrees with Ephrem’s “Greek” version in the ̈reading ܒ̈ܢܝ ܐܢܫܐ, so his alternate version finds support in the wider tradition of the separated gospels 67

We should also observe that Ephrem refers to this additional gospel text in a way that is parallel to the manner in which he refers to his standard gospel text. He titled his gospel exposition the Commentary on the Gospel (ܦܘܫܩܐ ܕܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ) and called the text upon which he commented simply the “Gospel” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ). However, when he refers to the alternate version in the Refutationes pb. 34 ad Hypatium, he offers no further description of this text beyond simply calling it the “Greek Gospel” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ܝܘܢܝܐ). In other words, pace Burkitt and Vööbus, he does not distinguish these two gospel versions on the basis of their form, but simply on the basis of their language. If Ephrem had been referring to a fourfold gospel, it seems likely that he would have needed to provide some further description to signal to his readers that this was a reference to a four-part gospel, in contrast to his singular, united gospel.

The remaining five references to “the Greek” all occur in Ephrem’s Commentary on the Gospel and present a pattern in keeping with the passage from the Refutationes ad Hypatium. In CGos V.2 Ephrem, while commenting upon the wedding feast at Cana, notes in passing “in Greek he wrote, ‘he was reclining and the wine ran short’” (ܒܝܘܢܝܐ ܟܬܒ ܕܣܡܝܟ ܗܘܐ ܘܚܣܪ ܚܡܪܐ) 68 When commenting on this passage Theodor Zahn pointed out that Ephrem’s version of “the Greek” represents a confusion of ἐκλίθη (“he reclined”) with ἐκλήθη (“he was invited”), a textual variant that does not appear in the Greek gospel tradition 69 Whether the written text Ephrem refers to actually had this reading or whether the confusion arose through oral translation from the Greek is impossible to determine. What this citation seems to add to Ephrem’s surrounding discussion is precisely the fact that Jesus “was reclining,” though it is unclear how this point serves the purpose of the paragraph which is to explain the Savior’s rebuke of his mother’s request. Since this citation does not in any obvious way serve Ephrem’s larger point, it is possible that he has included it simply as a sort of curiosity for his readers. He was obviously aware that his “gospel” text differed from the “Greek” in this instance, and this difference alone could have warranted comment.

At CGos X.14 Ephrem once more turns to “the Greek.” He cites his Syriac version of Matthew 11:25 as, “I give thanks to you, Father, who is in heaven” (ܕܡܘܕܐ ܐܢܐ ܠܟ ܐܒܐ ܕܒܫܡܝܐ), and pb. 35 then follows by noting, “the Greek says, ‘I give thanks to you, God, Father, Lord of heaven and earth’ and ‘that you have hidden [it] from the wise and revealed [it] to children’ (ܠܛ̈ܠܝܐ ܐܒܐ ܡܪܐ ܕܫܡܝܐ ܘܕܐܪܥܐ. ܘܕܟܣܝܬ ܡܢ ܚܟܝ̈ܡܐ ܘܓܠܝܬ ܡܘܕܐ ܐܢܐ ܠܟ ܐܠܗܐ). 70 The most obvious difference between the two passages is that the Syriac reads “Father who is in heaven,” while “the Greek” reads “God, Father, Lord of heaven and earth.” The initial citation given, which derives from Ephrem’s standard gospel text, reads like an amalgamation of Matthew 11:25 (ἐξομολογοῦμαί σοι, πάτερ, κύριε τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καὶ τῆς γῆς) and the Pater Noster of Matthew 6:9 (Πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς). Given that Ephrem’s “Gospel” involved Tatian’s editing of preexisting material, it is entirely possible that the prayer of Jesus recorded here was Tatian’s own combination of these two passages 71 On the other hand, the reading Ephrem here gives as coming from “the Greek” largely corresponds with the Greek version of the passage as given in Matthew 11:25 and Luke 10:21 (κύριε τοῦ οὐρανοὐ καὶ τῆς γῆς), although it has the unusual addition of “God. 72 The next reference to “the Greek” is a citation of Matthew 28:18 and it occurs in a short section consisting of three sentences that are absent from the Armenian recension. The fact that this passage shows up only in the Syriac version calls into question its authenticity, though we have at least to reckon with the possibility that the Armenian translator omitted this passage rather than that it was a later interpolation to the Syriac. After citing an expanded version of John 16:15 (“All that my Father has is mine and what is mine is my Father’s”), the Syriac continues beyond the Armenian pb. 36 and cites as further proof an expanded version of Matthew 28:18 (“All authority that is in heaven and on earth has been given to me by my Father”), before then quoting the same passage as it occurs in “the Greek. 73 In this instance the only difference between the Syriac and “the Greek” is that, whereas the Syriac reads “in heaven and on earth” (ܕܒܫܡܝܐ ܘܒܐܪܥܐ), ܕ” ,(the Greek” has “as in heaven, so also on earth” (ܐܝܟ ܕܒܫܡܝܐ ܐܦ ܒܐܪܥܐ). .(It is unclear in this instance what extra exegetical pay-off is gained from the “Greek” text that cannot be had from the Syriac. Equally puzzling is the fact that Ephrem’s original text, which stood in his Syriac harmony, is closer to the proper Greek version of Matthew 28:18 than the text which he says comes from “the Greek.” Ephrem’s “Greek” version contains the phrase “as in heaven, so also on earth” which seems more like a fairly close translation of Matthew 6:10c (ὡς ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ γῆς) rather than 28:18 (ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς), Similar to the two previous passages from “the Greek,” Ephrem’s citation here is an unusual rendering of the Greek text as it is available to us today.

Furthermore, both of the versions of Matthew 28:18 cited here, the Syriac and the Greek, have the unusual phrase “by my Father” that does not occur in the Greek gospel tradition. It is possible that the additional phrase “by my Father” is Ephrem’s own loose citation, since immediately preceding his quotation of Matthew 28:18 is a quotation of John 16:15 which speaks of the Son receiving “all that the Father has.” Alternatively, it is also possible that Tatian added this phrase to Matthew 28:18 when compiling his harmony. The Peshitta inserts a phrase from John 20:21 (“As my Father sent me, so also I send you”) immediately following Matthew 28:18, a reading that, as Burkitt pointed out, was probably taken over from the Old Syriac version, which happens to be lost in this section 74 As with so many of the peculiar Old Syriac readings, it is likely that this insertion derives ultimately from the influence of Tatian’s gospel 75 Further evidence to this point is that the Arabic Diatessaron likewise places John 20:21 pb. 37 immediately following Matthew 28:18 76 Viewed in this light, it is plausible that the Johannine-sounding phrase “by my Father” which Ephrem reads in Matthew 28:18 was also due to Tatian’s mixing of his Matthean and Johannine sources. Notably, the Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Theophania, which provides the only other early citation of this verse in Syriac, likewise includes the phrase “by my Father,” supporting the reading in Ephrem’s text 77 If it is plausible to regard this phrase as Tatian’s own addition, then it is striking that it shows up both in Ephrem’s Syriac gospel text as well as in his alternate “Greek” gospel.

The final two reference to “the Greek” occur in sections of the commentary for which the folios of Chester Beatty 709 are missing, and for which therefore only the Armenian recension is available. At CGos II.17 Ephrem is explaining the meaning of Simeon’s prediction to Mary that “You will remove the sword” (Amovebis gladium), a reading of Luke 2:35a that makes Mary the subject of the action, rather than the object as is read in the Greek gospel tradition (σοῦ αὐτῆς τὴν ψυχὴν διελεύσεται ῥομφαία) 78 Ephrem provides two alternate interpretations of the verse. He first connects Mary’s removal of the sword with the sword that guarded paradise after Eve’s failure, relying on the common typological link between Eve and Mary. His second interpretation is that the verse refers to Mary’s “denial” (negationem). Assuming that Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the same Mary present at the empty tomb in John 20:15, Ephrem regards this “denial” as her doubting when she pb. 38 encountered the risen Christ, when she thought that he was the gardener 79 It is in the midst of this second interpretation that the commentary introduces Luke 2:35b with the words, “the Greek says quite clearly, ‘the thoughts from many hearts will be revealed,’ that is, the thoughts of those who doubted” (Graecum clare quidem dicit: Revelabuntur ex multis cordibus cogitationes (nimirum) eorum qui dubitaverunt) 80 In this instance, Ephrem does not contrast the reading of “the Greek” with that which is given in his primary gospel text, so it is unclear what exegetical value he thought he could derive from the Greek version that could not be had simply from the Syriac. Nevertheless, “the Greek” version of this passage as reported by Ephrem does correspond well with the Greek text as it is known to us today (ἀποκαλυφθῶσιν ἐκ πολλῶν καρδιῶν διαλογισμοί) 81

However, there have been doubts as to the authenticity of this passage. Harris, Schäfers, Leloir, and Lange have noted that Isho‘dad of Merv later cites this very passage from Ephrem’s commentary, but notably omits the line that introduces the reading from “the Greek. 82 On this basis they concluded that the citation of “the Greek” must be a later interpolation. While this pb. 39 interpretation of the evidence cannot be ruled out, it seems to me that the passage in Isho‘dad reads more like a paraphrase of Ephrem’s commentary rather than an exact citation. Isho‘dad has clearly shortened the passage in the latter half of his quotation, since the version as it stands in the commentary is longer and more detailed. Isho‘dad includes no reference to the “gardener” of John 20:15, as does Ephrem’s original passage, and whereas Isho‘dad merely mentions the “miracles” of the Savior, the commentary explicitly names these marvels: the conception and birth. Given that Isho‘dad apparently compressed the passage when he cited it, it is possible that he simply chose to leave out Ephrem’s reference to “the Greek” which he probably found puzzling and ill-suited to his purpose. For this reason, I suggest we regard the reference “the Greek” here as Ephremic.

The final citation of “the Greek” in CGos also comes from a passage extant only in the Armenian. At CGos XIX.17 Ephrem is concerned to explain the meaning of Jesus’ prayer in John 17:5, which he initially cites as “Give me glory in your presence from that which you gave me before the world had been made” (Da mihi gloriam apud te ex illa, quam dedisti mihi, antequam mundus factus esset). In the following exegesis, the Syrian wants to make clear that the “glory” spoken of is understood as the glory which the Son previously possessed with the Father when the two were creating. Now that the Son is engaged in bringing to pass a new creation, Ephrem argues, he prays to receive this same glory from the Father. After pressing this point for a paragraph or so, he then recapitulates his argument, asserting that the “Give me” (Da mihi) refers to that glory which “he had before creatures, with the Father, and in the Father’s presence.” As proof for this interpretation he next asserts, “for the reading of the Greek also quite clearly says, ‘Glorify me with that glory which I myself possessed in your presence, before the world was’” (quoniam et lectio (Graeci) habet et aperte quidem dicit: Glorifica me, ait, gloria illa quam possidebam ego coram te, antequam esset mundus) 83 Ephrem’s citation of “the Greek” in this instance is a fairly close rendering of the Greek text as it is known pb. 40 to us today (δόξασόν με σύ, πάτερ, παρὰ σεαυτῷ τῇ δόξῃ ᾗ εἶχον πρὸ τοῦ τὸν κόσμον εἶναι παρὰ σοί). Unlike in the previous passage, he here cites both his gospel text as well as that of “the Greek,” so we are in a position to compare them. The primary difference seems to be that the first citation speaks of the glory given (quam dedisti mihi) to the Son by the Father before the world, whereas “the Greek” describes the Son as actually possessing this glory before the world (quam possidebam ego). Perhaps the latter rendering seemed to Ephrem to make the point “more clearly” that the Son actually had this glory previously and was therefore not simply receiving it for the first time.

What then are we to make of these passages? To begin with, as I have already suggested, it is unduly skeptical to reject them all as later scribal interpolations, as Schäfers has done 84 The fact that Ephrem engages in this sort of reading in the Refutationes ad Hypatium, in a passage whose authenticity no one disputes, implies that the references in the Commentary on the Gospel should be given the benefit of the doubt unless further arguments can be adduced against their authenticity. Furthermore, I suggest it is most likely that in these passages Ephrem really does refer to a Greek version, rather than simply a Syriac tetraevangelium, as Burkitt, Vööbus, and Lange assumed, since the study of Possekel has laid to rest the idea that Ephrem had no access to Greek sources. Ephrem’s labeling of this source as “the Greek” makes much more sense as a straightforward reference to a text written in Greek, rather than awkwardly supposing that by “Greek” he actually means “Syriac in a separated form.” If then it is an actual Greek version to which Ephrem refers, we should not be greatly surprised that the citations from “the Greek” correspond with neither the Vetus Syra nor the Peshitta.

However, we still have to contend with the fact that several of the “Greek” passages cited by Ephrem include readings that are nowhere to be found in the Greek gospel tradition, and at least one of these readings, the “by my Father” in Matthew 28:18, occurs both in his Syriac text as well as in the “Greek” version to which he refers. Moreover, it is striking that he provides no mention whatsoever of a difference in form between the “Gospel” and “the pb. 41 Greek Gospel.” Rather, his language denotes a difference of language, while conversely implying a similarity in the form in which these two gospels existed. In light of these observations I suggest we consider the possibility that in these passages Ephrem refers to a Greek version of Tatian’s gospel to which he had access in Edessa. The original language of Tatian’s gospel has been a subject of much debate, and I do not intend to enter into it here. However, there is good reason to think that Tatian’s work did exist in Greek, as well as in Syriac. The only Greek witness to have survived is the bit of parchment from Dura Europos dated to sometime before the destruction of the city by the Persians in 256- 257. Although David Parker, D.G.K. Taylor, and Mark Goodacre have attempted to show that this fragment does not derive from Tatian’s gospel, Jan Joosten has recently provided a convincing counter-argument 85 If Tatian’s work survived in a Greek version in Dura-Europos as late as the mid-third century, then the possibility must at least be considered that a copy was also housed in the library at Edessa a century or so later during Ephrem’s residence pb. 42 there 86 The fact that these readings from “the Greek” occur only during the final ten years of Ephrem’s life imply that this text was not available to him in Nisibis but was only found by him once he had relocated to Edessa. If Ephrem found in Edessa a Greek copy of the gospel text familiar to him in Syriac, he or perhaps some other bilingual Christian could easily have provided variant readings from the Greek to supplement his exposition of the Syriac text.

Of course, the evidence is too slim to allow us to conclude with certainty that Ephrem’s “Greek” version is a Greek Diatessaron, but nothing rules out the possibility and there is at least some slim evidence in its favor. This explanation of these references is, therefore, at least as plausible as the notion that Ephrem is referring to Greek, separated gospels, even if final certitude is beyond our reach. If the idea of him using a Greek Diatessaron initially strikes us as odd, this reaction might simply reflect the fact that history is written by the victors—in this case the fourfold, separated gospel—, and what seems strange to us now might have been commonplace in fourth-century Edessa. We know that a Greek version of Tatian’s work once existed. That pb. 43 Ephrem’s allusive references to the “Greek” might be to such a text is at least as plausible an explanation as any other.

Finally, we should observe the way in which Ephrem uses these cross-references. Vööbus argued that since Ephrem on one occasion (CGos XIX.17) calls this variant reading a lectio (the Syriac in this section is lost), implying authoritative scriptural status, the Syrian regarded this alternate text as the normative one, rather than the “Diatessaron” upon which he commented 87 In the previous century Harnack made a similar argument, though he held that Ephrem knew Greek and was making his own translation from the Greek separated gospels, while Vööbus regarded the text as a pre- Peshitta Syriac translation of the separated gospels 88 The conclusion that lectio here implies a more authoritative text is probably assuming too much on the basis of a single word. In my reading of these five passages, it seems that Ephrem introduces the variant readings simply as further evidence for the particular interpretation he wishes to pursue, rather than as the definitive and ultimately authoritative textual form. His practice is in keeping with the way many contemporary Greek authors were content to rely simultaneously on readings of the Septuagint alongside the Hebrew Old Testament, without choosing one text over another. It is notable that in the final two passages I considered above, Ephrem says “the Greek” “speaks clearly,” suggesting that he thought the Greek version was a more lucid rendering that better served his purpose. There is no hint in his exposition of any opposition between the Syriac “Gospel” and “the Greek Gospel,” and he seems happy to use either to illuminate the meaning of a given passage.

4. GOSPEL VERSIONS IN EPHREM’S CORPUS

In light of the above three lines of inquiry, there is no doubt that Ephrem had access to gospel versions beyond the Syriac gospel upon which he authored a commentary. Most significant is the conclusion that he knew some form of the fourfold gospel, which, in terms of its form, would have contrasted sharply with Tatian’s pb. 44 gospel. Although, as I have argued elsewhere 89 Tatian’s version was quite likely anonymous and intended as a way of erasing the memory of the evangelist traditions, it is clear that Ephrem knew the names of the four canonical evangelists, and had worked with these texts at least with respect to the Johannine prologue and the Matthean and Lukan genealogies. It is likely that this knowledge is due to his acquaintance with an early Syriac translation of the tetraevangelium. The sole surviving witnesses of the Vetus Syra date from the period after Ephrem’s death, but these may represent a much older translation attempt. In addition, Ephrem also made use of a Greek version of the gospel, which may have been a Greek edition of Tatian’s work.

This picture of Ephrem is broadly in keeping with what we can reconstruct of his context. Aphrahat, who wrote a few decades earlier than Ephrem and who lived further East under Persian rule, never mentions evangelist traditions nor does he name Tatian or the Diatessaron. Ephrem, living in Nisibis and eventually in Edessa, appears to be more in touch with the Greek-speaking world further west. I have already noted Possekel’s demonstration of his usage of Greek philosophical contexts, and we should also note his engagement with the Arian controversy of the fourth century. Given this greater contact with the Greek world, it would be surprising if Ephrem did not know of the gospel in its fourfold form. In fact, he clearly did, in keeping with his knowledge of other Greek sources.

Nevertheless, we should not overlook the significance of the rather obvious fact that when he came to author a commentary, he did so not upon Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, but upon Tatian’s gospel in its Syriac form. His authoring of the commentary suggests that for both he and his community this text held some kind of authoritative status. Defining the nature of this authority more precisely is, however, more difficult. The most likely explanation is that this Syriac gospel was the widely accepted liturgical gospel for Ephrem and many other Syriac-speaking Christians, as reported also by Theodoret a century later, who noted its usage in 200 of the 800 churches in his diocese. As the gospel regularly used liturgically, it would have seemed natural for Ephrem to have written an exposition of it, in a manner parallel to pb. 45 the way that Greek and Latin authors explained the meaning of the fourfold gospel used liturgically in their churches.

Yet, even if Tatian’s gospel served as his primary gospel version, Ephrem apparently felt free to supplement it with additional material from elsewhere, such as the alternate readings of the “Greek gospel,” and the genealogies of Jesus which were absent from his liturgical text. He also treats as authentic certain traditions about Mary, Zechariah, Elizabeth, and John the Baptist which were likely drawn from some text like the Protoevangelium of James 90

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ayres, Lewis. Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Baarda, Tjitze. The Gospel Quotations of Aphrahat, the Persian Sage: Aphrahat’s Text of the Fourth Gospel. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1975.

- ________. “‘The Flying Jesus’: Luke 4:29-30 in the Syriac Diatessaron,” Vigiliae Christianae 40 (1986): 313-341.

- Beck, Edmund. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Fide. CSCO 154, Scriptores Syri 73. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1955.

- ________.Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen contra Haereses. CSCO 169, Scriptores Syri 76. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1957.

- ________. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Nativitate (Epiphania).CSCO 186, Scriptores Syri 82. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1959.

- ________. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones de Fide. CSCO 212, Scriptores Syri 88. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1961.

- ________. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Virginitate. CSCO 223, Scriptores Syri 94. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1962.

- ________. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Fide. CSCO 155, Scriptores Syri 74. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1967.

- ________. “Der syrische Diatessaronkommentar zu Jo. 1, 1-5,” Oriens Christianus 67 (1983): 1-31.

- Brock, Sebastian. “Mary and the Gardiner: An East Syrian Dialogue Soghitha for the Resurrection,” Parole de l’Orient 11 (1983): 225-26.

- ________.The Luminous Eye: The Spiritual World Vision of Saint Ephrem the Syrian. Cistercian Studies 124. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1992.

- ________. “Eusebius and Syriac Christianity.” In Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism, ed. Harold W. Attridge and Gohei Hata, Studia Post-Biblica 42. Leiden: Brill, 1992.

- ________. “The Use of the Syriac Fathers for New Testament Textual Criticism.” In The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, ed. Bart D. Ehrman, and Michael W. Holmes, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Bruns, Peter. “Arius Hellenizans? Ephraem der Syrer und die neoarianischen Kontroversen seiner Zeit. Ein Beitrag zur Rezeption des Nizänums im syrischen Sprachraum,”Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 101 (1990): 21-57.

- Bundy, David. “The Letter of Aithallah (CPG 3340): Theology, Purpose, Date.” In III Symposium Syriacum 1980, ed. René Lavenant. Rome: Pont. Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1983.

- ________. “Revising the Diatessaron Against the Manicheans: Ephrem of Syria on John 1:4,” Aram 5 (1993): 65-74.

- ________. “The Creed of Aithallah: A Study in the History of the Early Syriac Symbol,” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 63 (1987): 157-163.

- Burkitt, F.C. S. Ephraim’s Quotations From the Gospel. Texts and Studies 7.2. Cambridge: The University Press, 1901.

- ________. Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe. 2 vols. Cambridge: The University Press, 1904.

- Crawford, Matthew R. “Diatessaron, A Misnomer? The Evidence of Ephrem’s Commentary,” Early Christianity4 (2013): 362-85.

- ________. “Reading the Diatessaron with Ephrem: The Word and the Light, the Voice and the Star,” Vigiliae Christianae, forthcoming.

- S. Ephræm Syri commentarii in epistolas D. Pauli(Venice: Typographia Sancti Lazari, 1893).

- Gibson, Margaret Dunlop. The Commentaries of Isho’dad of Merv, Bishop of Hadatha (c. 850 A.D.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Graffin, F. Patrologia Orientalis 41. Turnhout: Brepols, 1982.

- Griffith, Sidney H. “Setting Right the Church of Syria: Saint Ephraem’s Hymns Against Heresies.” In The Limits of Ancient Christianity: Essays on Late Antique Thought and Culture in Honor of R. A. Markus, ed. William E. Klingshirn and Mark Vessey. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Harnack, Adolf. “Tatian’s Diatessaron und Marcion’s Commentar zum Evangelium bei Ephraem Syrus,” Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 4 (1881): 471-505.

- Harris, J. Rendel. Fragments of the Commentary of Ephrem Syrus Upon the Diatessaron. London: C.J. Clay and Sons, 1895.

- Horn, Cornelia B. “Syriac and Arabic Perspectives on Structural and Motif Parallels Regarding Jesus’ Childhood in Christian Apocrypha and Early Islamic Literature: The ‘Book of Mary,’ the Arabic Apocryphal Gospel of John and the Qu’rān,” Apocrypha 19 (2008): 267-291.

- Joosten, Jan. “The Dura Parchment and the Diatessaron,” Vigiliae Christianae 57 (2003): 159-175.

- Kiraz, George Anton. Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels. 4 vols. Brill: Leiden, 1996.

- Kraeling, Carl H. A Greek Fragment of Tatian’s Diatessaron From Dura. Studies and Documents 3. London: Christophers, 1935.

- Lange, Christian. “Zum Taufverständnis im syrischen Diatessaronkommentar.” In Syriaca. Zur Geschichte, Theologie, Liturgie und Gegenwartslage der syrischen Kirchen. 2. Deutsches Syrologen-Symposium (Juli 2000, Wittenberg), ed. M. Tamcke. Studien zur orientalischen Kirchengeschichte 17. Münster: Lit, 2002.

- ________. The Portrayal of Christ in the Syriac Commentary on the Diatessaron, CSCO 616, Subsidia 118. Louvain: Peeters, 2005.

- ________. “Ephrem, His School, and the Yawnaya: Some Remarks on the Early Syriac Versions of the New Testament.” In The Peshitta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read At the Third Peshitta Symposium, ed. Robert Bas ter Haar Romeny, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute Leiden 15. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- ________. Ephraem der Syrer. Kommentar zum Diatessaron. 2 vols. Fontes Christiani 54/1-2. Turnhout: Brepols, 2008. .

- Leloir, Louis. Saint Éphrem. Commentaire de l’Évangile concordant, version arménienne. CSCO 145, Scriptores Armeniaci 2. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1954.

- ________. L’Évangile d’Éphrem d’après les oeuvres éditées: Recueil des textes. CSCO 180, Subsidia 12. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1958.

- ________. Le témoignage d’Éphrem sur le Diatessaron. CSCO 227, Subsidia 19. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1962.

- ________. Saint Éphrem, Commentaire de l’Évangile concordant, texte syriaque (Manuscrit Chester Beatty 709). Chester Beatty Monographs 8. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co., 1963.

- ________. Éphrem de Nisibe: Commentaire de l’Évangile concordant ou Diatessaron. Sources Chrétiennes 121. Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1966.

- Lewis, Agnes Smith. Apocrypha Syriaca: The Protevangelium Jacobi and Transitus Mariae, with Texts from the Septuagint, the Corân, the Peshitta, and from a Syriac Hymn in a Syro-Arabic Palimpsest of the Fifth and Other Centuries. Studia Sinaitica 11. London: C.J. Clay and Sons, 1902.

- Marmardji, A. S. Diatessaron de Tatien. Beirut: Imprimerie catholique, 1935.

- Matthews, Edward G. The Armenian Commentary on Genesis Attributed to Ephrem the Syrian. CSCO 573, Scriptores Armeniaci 24. Louvain: Peeters, 1998.

- ________. The Armenian Commentaries on Exodus-Deuteronomy Attributed to Ephrem the Syrian. CSCO 587, Scriptores Armeniaci 25. Louvain: Peeters Publishers, 2001.

- McCarthy, Carmel. Saint Ephrem’s Commentary on Tatian’s Diatessaron: An English Translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709. Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement 2. Oxford: Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the University of Manchester, 1993.

- Mell, Ulrich. Christliche Hauskirche und Neues Testament. Die Ikonologie des Baptisteriums von Dura Europos und das Diatessaron Tatians. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus 77. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010.

- Mitchell, C.W. S. Ephraim’s Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Volume I: The Discourses Addressed to Hypatius. Text and Translation Society. London: Williams and Norgate, 1912.

- Murray, Robert. “The Lance Which Re-Opened Paradise, a Mysterious Reading in the Early Syriac Fathers,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 39 (1973): 224-234, 491.

- ________. Symbols of Church and Kingdom: A Study in Early Syriac Tradition. Rev. ed. London: T&T Clark, 2006.

- McVey, Kathleen E. Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989.

- Naffah, Charles. “'Les ‘histoires’ syriaques de la Vierge: traditions apocryphes anciennes et récentes,” Apocrypha 20 (2009): 137- 188.

- Parker, D.C., D.G.K Taylor, and M.S. Goodacre. “The Dura- Europos Gospel Harmony.” In Studies in the Early Text of the Gospels and Acts, ed. D.G.K. Taylor. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1999.

- Pastorelli, David. “The Genealogies of Jesus in Tatian’s Diatessaron: The Question of their Absence or Presence.” In Infancy Gospels: Stories and Identities, ed. Claire Clivaz, Andreas Dettwiler, Luc Devillers, and Enrico Norelli. WUNT 281. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011.

- Petersen, William L. Tatian’s Diatessaron: Its Creation, Dissemination, Significance, and History in Scholarship. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 25. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994.

- Possekel, Ute. Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian. CSCO 580, Subsidia 102. Louvain: Peeters, 1999.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. “Neue Fragmente zum Diatessaronkommentar des Ephraemschülers Aba,” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 11 (1980): 117-133.

- Schäfers, J. Evangelienzitate in Ephraems des Syrers Kommentar zu den paulinischen Schriften. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1917.

- Thorossian, Joannes. Aithallae Episcopi Edesseni Epistola Ad Christianos in Persarum Regione De Fide. Venice: Lazari, 1942.

- Tonneau, R.-M. Sancti Ephraem Syri in Genesim et in Exodum Commentarii. CSCO 152, Scriptores Syri 71. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1955.

- Urbina, Ignatius Ortix de. Vetus Evangelium Syrorum et Exinde Excerptum Diatessaron Tatiani. Biblia Polyglotta Matritensia, Series VI. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1967.

- Vööbus, Arthur. Studies in the History of the Gospel Text in Syriac. CSCO 128, Subsidia 3. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1951.

- Walters, J. Edward. “The Philoxenian Gospels as Reconstructed from the Writings of Philoxenus of Mabbug,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 13 (2010): 177-249.

- Watson, Francis. Gospel Writing: A Canonical Perspective. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013.

- Williams, Peter J. “The Syriac Versions of the New Testament.” In The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, ed. Bart D. Ehrman, and Michael W. Holmes. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Wright, William and Norman McLean. The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius in Syriac. Cambridge: University Press, 1898.

- Zahn, Theodor. Tatian’s Diatessaron, Forschungen zur Geschichte des neutestamentlichen Kanons und der altkirchlichen Literatur, Tl. 1 Erlangen: Deichert, 1881.

Footnotes

1 1 William L. Petersen, Tatian’s Diatessaron: Its Creation, Dissemination, Significance, and History in Scholarship, Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 25 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994), 115-116.

2 2 Ephrem’s disciple Mar Aba also wrote a commentary on Tatian’s gospel that survives in fragments. Cf. Gerrit J. Reinink, “Neue Fragmente zum Diatessaronkommentar des Ephraem-schülers Aba,” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 11 (1980): 117-133.

3 3 Sozomen, h.e. 3.16.3-4.

4 4 Sebastian Brock, The Luminous Eye: The Spiritual World Vision of Saint Ephrem the Syrian, Cistercian Studies 124 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1992), 15.

5 5 Ibid., 160.

6 6 Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian, CSCO 580, Subsidia 102 (Louvain: Peeters, 1999).

7 7 For an up-to-date introduction to early Syriac versions, see Peter J. Williams, “The Syriac Versions of the New Testament,” in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, 2nd ed., ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 143-166.

8 8 F.C. Burkitt, S. Ephraim’s Quotations From the Gospel, Texts and Studies 7.2 (Cambridge: University Press, 1901), 56. The articles of T. Baarda over the past several decades have mounted much additional evidence for Ephrem’s usage of the so-called “Diatessaron.” See, e.g., “‘The Flying Jesus’: Luke 4:29-30 in the Syriac Diatessaron,” Vigiliae Christianae 40 (1986): 313-341.

9 9 Ephrem, Hy. de fide 48.10 (Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Fide, CSCO 154, Scriptores Syri 73 (Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1955), 154). I am grateful to Paul S. Russell for allowing me to consult his pre-publication version of the English translation of these hymns, which I reproduce above.

10 10 Hippolytus, comm. Dan. 1.18; Cyprian, ep. 73.10.3; Victorinus, In Apoc. 4.4; Jerome, comm. Mt., prol.

11 11 Cf. Louis Leloir, Le témoignage d’Éphrem sur le Diatessaron, CSCO 227, Subsidia 19 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1962), 72-73; Christian Lange, “Ephrem, His School, and the Yawnaya: Some Remarks on the Early Syriac Versions of the New Testament,” in The Peshitta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read At the Third Peshitta Symposium, ed. Robert Bas ter Haar Romeny, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute Leiden 15 (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 166-67.

12 12 Tjitze Baarda, The Gospel Quotations of Aphrahat, the Persian Sage: Aphrahat’s Text of the Fourth Gospel (Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1975), 323-324, disagreeing with F.C. Burkitt, Evangelion Da- Mepharreshe, 2 vols. (Cambridge: The University Press, 1904), II.180, regards the two words as synonymous for Aphrahat, since in his usage “both words may mean both the Gospel-Book and the Good Message.” Baarda does not discuss Ephrem’s usage of the terms. 13 Cf. Matthew R. Crawford, “Diatessaron, A

13 13 Cf. Matthew R. Crawford, “Diatessaron, A Misnomer? The Evidence of Ephrem’s Commentary,” Early Christianity 4 (2013): 362-85.

14 14 So also Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Fide, CSCO 155, Scriptores Syri 74 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1967), 131.

15 15 Ephrem, Ser. de fide 2.39-48 (Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones de Fide, CSCO 212, Scriptores Syri 88 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1961), 8-9). Cf. Lange, “Ephrem, His School, and the Yawnaya,” 167.

16 16 See haer. 3.11.8.

17 17 Ephrem, Hy. de virg. 51.2 (Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Virginitate, CSCO 223, Scriptores Syri 94 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1962), 162).

18 18 Ephrem, Hy. contra haer. 22.1 (Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen contra Haereses, CSCO 169, Scriptores Syri 76 (Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1957), 78). I have here used the unpublished translation of Adam C. McCollum which can be accessed at http://archive.org/details/ EphremSyrusHymnsAgainstHeresies22

19 19 Burkitt, Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe, II.31. My translation differs slightly from that of Burkitt.