Gišeroy kcʿurdkʿ (Hymns of the Night)

Seven Madrāše of Ephrem the Syrian Preserved in Armenian

This paper treats the collection of fifty-one hymns (madrāše) of Ephrem the Syrian that survive in Armenian translation (Arm. kc‘urdk‘), with a particular focus upon one cycle of seven, the Hymns of the Night (Gišeroy kc‘urdk‘), which treat the topic of vigil. After a brief discussion of the collection as a whole, an annotated English translation of the Hymns of the Night (kc‘urdk‘ 10-16) is made for the first time. Following this is a commentary that discusses linguistic, historical and thematic evidence that supports the attribution to Ephrem and points towards a fifth-century date for the translation from Syriac to Armenian.

Introduction to the Kc‘urdk‘

1Among the profuse corpus of extant Armenian texts attributed to Ephrem the Syrian are fifty-one pieces called kc‘urd (կցուրդ), the Armenian rendering of the Syriac madrāšā. Although traditionally translated into English as ‘hymn,’ madrāšā might be better rendered as ‘teaching song,’ which captures the twin components of this Syriac genre, at the nexus betwen didactic literary work and liturgical hymn.2 The Syriac root drš, ‘to tread out (a path)’ with its derived meaning of ‘to train, instruct,’ indicates the didactic origin of the genre,pb. 268 immediately bringing to mind as well the Hebrew tradition of midraš, and its association with interpretation and debate. It is likely that at the earliest stage the madrāšā genre was a purely literary one (i.e. not sung), and probably prose rather than poetry.3 Ephrem himself cites the second/third-century figure Bardaiṣan as the one responsible for transforming this prose genre into measured verse with melodies.4 Ephrem, following Bardaiṣan’s lead, became the most celebrated composer of madrāše, employing it for his own instructive and polemical purposes. The combination of verse and song made for an effective means of polemics in the contested religious environment of the fourth century in addition to providing a means of edification for hearers and a fit medium for Ephrem’s poetic and symbolically rich thought world and theological method.5

By the time of the fifth century — the earliest possible period at which the madrāše of Ephrem could have been translated into Armenian, due to the invention of Armenian letters in the fifth century — madrāšā referred to a type of liturgical hymn, already present in all Syriac traditions, ofpb. 269 isosyllabic lines arranged in strophes sung by a soloist, with a short refrain sung by a choir, the singers often being women.6 The Armenian term kc‘urd (կցուրդ), like the fifth-century madrāšā, refers to strophic, often antiphonal liturgical poetry, usually sung in connection with the celebration of a feast-day.7 It is derived from the verb kc‘em (կցեմ), meaning “to join, unite, tie,” and could refer either to the joining together of syllables and words into metric verse, or the joining together of voices in song.8 In connection with this, the standard word for hymn in Armenian, šarakan (շարական) from the root šar/šarem (շար/շարեմ) shares this sense of ‘ordering, arranging.’9

The complete collection of Ephrem’s fifty-one Kc‘urdk‘ were first published in a diplomatic edition by Nersēs Akinian of the Vienna Mekhitarist order of scholar-monks in 1957.10 A few years later this text was reproduced by Louis Mariès and Charles Mercier along with an introduction and annotated translation into Latin.11 Corrections and further variant readings from manuscripts not consulted by Akinian were added by Levon Tēr-Petrosian in a later study.12 Over the years,pb. 270 there have been a number of scattered translations of individual hymns, often with brief studies accompanying them, in French and English.13

Akinian’s diplomatic Armenian text is largely derived from two manuscripts: Matenadaran 821 and Nicosia (Cyprus) 8 (now Antelias 85).14 Kc‘urdk‘ 16-51 are provided from the former and 1-15 from the latter. Matenadaran 821 is a religiouspb. 271 miscellany (ժողովածոյ) copied in 1313 at the monastery of Akner (Ակներ) in Cilicia.15 It contains only Kc‘urdk‘ 16-51 because the initial pages of the manuscript are missing, resulting in the loss of the first 15 Kc‘urdk‘. Occasional pages or portions of pages are also missing or damaged (as well as some being out of order), leading to lacunae in later Kc‘urdk‘. The manuscript was already in a defective state when it was repaired in 1596 at T‘lkuran (Թլկուրան) near Edessa, as is clear from the colophon of the renewer who begged the reader’s forgiveness for the missing initial pages and their mixed-up order.16

From this we can conclude that by 1313 when the manuscript was copied, it contained all 51 Kc‘urdk‘ of Ephrempb. 272 as a single collection. Unfortunately however, all the manuscripts derived from this copy were undertaken after it had become defective. In 1939 on a trip to Cyprus, Akinian discovered Nicosia 8 (now Antelias 85), which contained the missing initial fifteen Kc‘urdk‘, as well as Kc‘urdk‘ 47-51 (it therefore lacks numbers 16-46).17 It is a collection of religious texts, compiled mostly from the lives and writings of the Fathers, and was copied in the fourteenth century. It is in a deteriorated state, but nonetheless for the most part filled the gaps of Matenadaran 821 by supplying the texts (with some lacunae) of the first fifteen Kc‘urdk‘.

It is highly unlikely that the fifty-one Kc‘urdk‘ of Ephrem surviving in Armenian were all derived from an original cycle of fifty-one madrāše put together as such in the fourth century by Ephrem, but rather were pulled together at some point, presumably by the Armenian translator(s), from different Syriac originals. The surviving fifty-one Kc‘urdk‘ treat a variety of different topics, but can be broken down into at least three major sub-groupings, perhaps representative of three originally separate cycles of madrāše: Kc‘urdk‘ 1-9 treat virginity and holiness; Kc‘urdk‘ 10-16 all contain the superscript Գիշերոյ կցուրդ (Gišeroy kc‘urd, “Teaching Song of the Night”) and have to do with vigil; Kc‘urdk‘ 17-51 in one way or another all treat the topic of eating, in particular the Lord feeding his creatures, with topics derived from everyday life and the Scriptures, including the Lord feeding his creatures through mysteries (rāze), such as the Eucharist (Kc‘urdk‘ 47-51). These three larger themes likely reveal the taste of the Armenian translator(s),pb. 273 who chose these particular hymns for their relevance to the Armenian ecclesiastical context.

Most scholars have assumed an early date for the translation of these texts, supposing that they come from the initial translation movement of Maštoc‘ and his students in the fifth century. No scholars who have worked on the Kc‘urdk‘ have found grounds for questioning either the authenticity of their attribution to Ephrem or the early date of translation.18 There has however been very little effort to give concrete evidence for either of these two suppositions. In light of recent studies of Edward Mathews demonstrating that many of the works translated from Syriac into Armenian — both those attributed to Ephrem and as well as the works of other writers — actually date from the Cilician period (especially the twelfth–thirteenth centuries) when there was a sizeable Syriac community living within the Armenian realm, as opposed to the fifth-century provenance that previous scholars had simply assumed for most Syriac works in Armenian, it seemed worthwhile to investigate the attribution and provenance of these texts by examining the concrete linguistic evidence of the texts as well as some historical and thematic evidence.19

After conducting my investigation into this question, I believe the evidence strongly favors the view to date that these texts issue from authentic Syriac originals of Ephrem rendered into Armenian in the fifth century. This article focuses on the cycle of seven Gišeroy kc‘urdk‘ that treat the topic of vigil, providing an annotated translation as well as a commentary pb. 274 providing mostly linguistic evidence that supports their authentic attribution to Ephrem. A translation of all fifty-one Kc‘urdk‘ into English is currently under preparation.

Annotated Translation

20Kc‘urd 10 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 1]

Blessing, Hymn of the First Night

O Son, glorified by the sleepless ones; blessing to You from those keeping watch.

1 O watchers, be like Moses, the chief of the Hebrews,

He who estranged himself from sleep during the days in which he stood on the mountain;21

But from the hour that he became a [seer of] god22 and his face was illumined,

Sleep feared to approach his eyes, which had put on23 glory.

5 For the veil of Moses was limiting the vision of all thepb. 275 people,

Who would remain outside all the walls, and did not have the temerity to pass from outside the veil to be with him.24

Although sleep was hovering near to Moses within the veil,

If he were to enter [sc. into sleep], he would be killed by the glory right away.

Since even without the glory, he had banished the sleep of eighty nights,25

10 After he had put on26 glory, how much more would he banish it!

But so that the people would not err and think that he was not a man,

He would doze off lightly, in order to teach them that he is earthly and not celestial.27

And because he had trained himself and had become a watcher by a little effort of his will,

Behold, he estranged himself from sleep, from the days of our Lord up until now.

15 Concerning his coming to Tabor,28 Scripture says,29

“Afterwards he slept no more, but he stands with the sleepless ones in sleep.”30

pb. 276And Joshua son of Nun31 was a dweller in the tent of meeting, as it is written.32

Through his dwelling in the holy place, he banished the sleep of his eyes,

And the desire of his body parts, and the dozing and sleep of his pupils.

20 Modesty dwelt in his heart, and wakefulness in his eyelids.

Sleep and desire are natural, and both were conquered by Hoshea.33

Because he who conquers desire of the body is able to conquer sleep of the eyes.

He submitted himself to sleep for a little, but to desire not ever at all.

Sleep was struck off from his eyes, and desire did not rule in his heart.

25 Along with this same example, Elijah banished sleeppb. 277 from his eyes,

Because for forty nights his eyelids fasted from sleep.34

And because he trained himself in watching in his journey on Mount Horeb,35

That watching of a short time made him a watcher forever.36

Job was awake in his testing to seek and receive from his Lord

30 Thanksgiving instead of complaining and blessing instead of blasphemy.37

Jonah kept watch during the nights in which he was in the womb of the fish;

He was buried in the fish and the sea, but sleep did not reign over his eyes.38

The wakefulness of the son of Amathias surprised and amazed the big fish,

Because he did not even want to bend his knee so long as he was in the belly of the fish.

35 Jonah fled from God because he thought in his ignorance

That the Holy One and Glorious One dwells only in the land of Promise.39

But when he descended into the floor of the sea, he learned from his own experience

That not only on the earth is that Holy One, but also in the abyss of the depths of the sea.40

pb. 278Jeremiah was awake in the pit to make prayers for his murderers;

40 Through his occupation with God, he estranged himself from the foul pit.41

Ezekiel banished his sleep for four hundred and thirty days,42

For he fasted from sleep, as he fasted from food.

By the same measure [with which he measured] his food, he measured the sleep of his eyes,

And since his food was little, he would only moisten his palate.43

45 By the [measure of the] little water which he would drink, he would lead eye to eye for a short time,

And before having slept, right on the spot he would wake up.

Kc‘urd 11 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 2]

Hymn of the Second Night

Blessed is the one who comes and makes glad the watchers at his appearance.

1 Be sober a little while, O virtuous ones, lifting up the heaviness of darkness.

Because behold, a little while44 and [night] has completed its hours, and morning comes and makes us glad.

At night, the disciples kept watch, yet because theypb. 279 dozed off,

Out of wrath, the teacher severely reproached the twelve.45

5 The establisher of that nature would not have compelled them [sc. to stay awake],

If he had not known that humanity is able to conquer sleep;

And he would not have laid down a commandment again,

If he had not known that [sleep] could be conquered.

Scripture says, “Be watchers, to guard the hour of the bridegroom who is to come.”46

10 He gave us four watches47 to guard, throughout all the nights of our life,

So that in whichever of them he comes, he will find his church awake.

Although he hid his day and his hour, and did not reveal the hour of his dawning,

Yet behold, he foretold through the four parts that in the night his revelation is made.48

Let us keep therefore the hour of the groom, as we received a commandment,

15 Because even if he does not come in our days, his trustworthiness will not defraud us.49

“As you will be found, you will be led,”50 said the teacherpb. 280 to his disciples.

Let us chase away sleep from our eyes, to be ready at his coming.

Unexpectedly, the lightning flashes; thunder cracks and causes fright.

Unexpectedly, the firstborn hastens, and he stirs the powers of the heavens.51

20 The violence of lightning flashes and the terrors of all thunderings

Are as a breath and as nothing in the eyes of the revelation of Christ.

The sun grows dark from his [sc. Christ’s] face, and the moon is obstructed from the face of his glory.52

Darkness is erased and diminished through the dawning of the great sign.53

Sleep and slumber of the eyes falls away, and desire of body parts is removed,

25 And one wakefulness spreads out, which does not diminish.54

Everyone who keeps55 the hours of the groom, he makes glad at his appearance.

Because those who remove the heaviness from their life are right to put to sleep their body parts.

Let us keep watch as much as we are able, and not lesspb. 281 than our ability.

Our laziness is reproached by the strong ones who toil among us, for we did not keep watch in the evening.

30 Let us by no means be half-awake,56 for there is one who keeps watch the whole night; let us keep watch at least half.57

What benefit is it that we slept yesterday, since we will sleep again today?

Watchers abound in prayers, while sleepers are numbered by their dreams.58

The breaths of watchers are purified and their minds become chaste,

While in the breath of sleepers the error of deceptive visions is gathered.

35 The breath of watchers is glorified through their occupation with God,

While the breath of sleepers is a game for the Evil One.

In their dreams, they are befouled through their visions, and passions seize power over them,

And sleep, which they thought was rest, became entirely disturbed.pb. 282

They wander through many places and roam, and they suffer to no benefit.

40 In all directions they soared and returned, although they were not removed from their bodies.

Because they were not engaged in the watching of God, Satan seized power over their visions.

Because they did not gather at the door of their Lord, they were dispersed through their visions to their souls’ harm.59

The benefits of watchers were multiplied unto them, while the dreams of sleepers were multiplied unto them.

The toil of watchers is preserved, while the accumulation of dreams turns to nothing.

45 May there be a memorial for me among you, O watchers,

Who lifted up the heaviness, because others did not keep watch.60

Behold I exhort the multitude, that they may become awake.

Kc‘urd 12 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 3]

Hymn of the Third Night

May the watchers, who became worthy to become a companion of the holy seraphim, thank You.

1 Do not grant authority to sleep to reign over your bodypb. 283 parts;

Hear the calamities, which it worked on earth; shudder with fear, and flee from it.61

Adam was plundered in sleep, by the rib that was taken from him.

In wakefulness, he was one; when he slept, he was divided, and turned into two.62

5 Noah was greatly ridiculed through his sleep, by the one who was born from him;

In wakefulness he was sober and temperate; in his sleep, he became naked and was exposed to shame.63

Lot also, through his sleep, was plundered and did not sense it.

The wakeful ones became wealthy from his treasure, and from his seed they turned into nations.64

For if sleep worked this against the just, and they did not sense it while it was robbing them,

10 How much more ought we sinners to fear sleep so that it not reign over us!

The firstborn of Egypt died in sleep, and that misfortunate one [sc. Pharaoh] did not sense it;

But after he awoke and got up, then he felt his blow.65pb. 284

Sisera, who through his gigantic strength slaughtered the nation of the Hebrews,

Became as great in his wakefulness, as he was weakened through sleep.

15 For Jael rose up against him and drove a stake through his jaws;

Sleep made him into a disgrace, for by the hand of a woman it killed him.66

Samson,67 who had taken an oath,68 who from the womb had been clothed with gigantic strength,

Who had burned Philistia69 — through a woman, the Philistines blinded his eyes.70

He who killed that lion71 and with foxes burned Philistia,72

20 Sleep duped and robbed him, and in the daytime tied him to a millstone.

At night, Midian was pillaged by the wakeful ones, who were with Gideon.73

At the sound of the trumpets, Midian was roused and woke up, arose and struck itself with the sword.74

The hands of the wakeful ones were not smeared in the blood of the drowsy sleepers.

By the lanterns and shouts of the wakeful one, it was polluted in its own blood.

25 Gideon was vigilant in prayer,75 and dreams were making Midian flow.pb. 285

They prophesied victory to it, but defeat came to it.

Saul was plundered in sleep, for he lost the hem of his robe.76

Through the hem which [David] cut, he took the royal rule from him.

And because he [sc. Saul] did not shudder in fear from it [sc. sleep], he continued and slept again.

30 He remained deprived of his weapon, because his spear was taken from him.77

Life after that sleep, David granted to him as a gift;

For after that sleep which was in the cave, he slept an eternal sleep.

And because the Rabshakeh blasphemed and slept, an angel smashed his army,78

And the seed that he sowed in the day, he reaped in the night.

35 Behold the Rabshakeh was sleeping on his couch, while Hezekiah was awake in prayer.79

The sleepless one descended at the prayers of the wakeful one, and slaughtered the camps of the sleepers.80

Sion was full of prayers, and the camp of Assyria with dead people.

The watchers made the sleepers who blasphemed slumber in an eternal sleep.

In the night, Babylon was pillaged by the Medes, who were vigilant.81pb. 286

40 Sleep handed over the marvelous one [sc. Babylon] to death along with the whole country.

For he who sleeps along with the wakeful one — they are one, and they are not one.

The rest of sleep does not endure, but the recompense of prayers is stored up.

This labor which is in our body parts, multiplies for us benefit in the heights.

Our labor passes away, but our reward endures forever.82

Kc‘urd 13 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 4]

Hymn of the Fourth Night

Blessed is He who made worthy the sons of Adam to sing psalms with the angels.

1 Blessed are the watchers, who in all nights are arrayed against sleep.

Daniel was awake in the den, and the wild beasts were keeping watch with him;83

The night was too short to give thanks for his salvation that came about for him.

Darius also drove away sleep; he estranged himself also from delicacies.

5 He did not give rest to his body because of his love for Daniel.84

Throughout that time in which Daniel fasted from the delicacies of the kingdom,

He was sober in all his hours for he was awake in all his hours.85

He drove away sleep from his pupils, in order to call onpb. 287 his God,

In order that by sign and manifestation, insults might be blocked from his people.

10 Through vigil he persuaded God to show him the dream of the king.86

And through his and his companions’ vigil, [God] revealed to him [sc. Daniel] the dream and His [sc. God’s] interpretation.87

The Chaldaeans and sorcerers entered and were confounded, because they did not comprehend it.88

The watcher entered and told the dream, and along with the dream its interpretation.

Because that which the king saw as he was sleeping in the house of his kingdom,

15 The prayers of the watchers made vividly clear before the king and his companions.

The Chaldeans were saved by the vigil that the youths kept,89

Because vigil shone upon it and revealed the dream that was concealed from the sorcerers.

Through wakefulness and soberness, you are similar to the sleepless ones on high,

And to the prophets through your halleluias, and to the Seraphim through your holinesses,90

20 To the assembly that blessed in Ephrath91 at night atpb. 288 the dawning of our Savior.92

Behold, may your hosts resemble93 them through the blessing94 that your mouths are thundering.

The Magi who had sensed concerning the only-begotten Son because they had banished the sleep of their eyes,

Were hastening throughout all the nights, with the illuminating star guiding them.95

The apostles kept watch the whole night to catch fish, but did not find any.

25 In the morning their minds rejoiced at the great catch they had found.96

Our Lord passed the night in prayer once it became evening, in order to be an example to watchers.97

Blessed are you, who studied with that teacher, the firstborn son who taught you.

He is Lord of both — wakefulness and sleepiness — if he came into both, since both are for us.

As he slept for us, so also he kept watch for us.

30 Through sleep he alluded to his body, and through watching he banished our bouts of sleepiness.

Because he came into the world, which is subject to wakefulness and to sleepiness,

He subjected himself to both, since he was close to both.

Because if watchfulness were not good, then the Son would not have become an example of it;pb. 289

Without keeping watch, no one is able to alienate oneself from all evils.

35 Let us become disciples of Him rightly, so that his life may become perfected in us.

Let us not become disciples half-heartedly, lest we become sleepers and not watchers.

The Son, who was not in need of keeping watch, became a watcher for our sake.

He fashioned it as a weapon and gave it to us, so that our discipleship would bear fruit in virtue.

Kc‘urd 14 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 5]

Hymn of the Fifth Night

Blessing to the Son, who makes glad the watchers by His dawning.

1 King David, who thought to build a temple for God,98

Made a voluntary covenant to not give sleep to his eyes.99

He distanced himself from his own house, because he saw that far away

That ark, which was full of the mystery of Christ,100 had been neglected.101

5 The king estranged himself from his own house andpb. 290 from the mattress of his bed;

He pitched for himself a tent instead of a house, and spread out sackcloth on the ground.

And so that his body would not become heavy, he gave it food in moderation.

He deprived himself of everything, so that he would be capable of fulfilling his covenant.

From his house and his bed David was able to estrange himself,

10 While from his sleep, how was he able to estrange himself?

He wanted to know the place, and he had set his desire on building the temple.

And he made a covenant for this reason, and he actualized it through his oath.

He swore to the Lord and made a covenant with him to not give sleep to his eyes,

Nor slumber to his eyelids until he find the place of the Lord.102

15 He descended into great humility until he saw that place;

And in the hour that he learned of the place, the covenant of his mouth was fulfilled.

He did not want to offer anything other than things from that place,103

So he offered what was found from the same and from the same place.

The king’s oxen were found in the same place, and it was not lacking wood.

20 With the wood and oxen that were of that place, he sacrificed to the Lord of that place.pb. 291

And because it was a prodigious oath, the Lord worked in him greater things.

Because through the fire from above, his sacrifice became acceptable.104

God showed him the place that he sought, and he blocked death from his nation.

And why did [God] not allow him to build the house?

25 The great things that are not worked, the Lord his benefactor worked for him,105

And God prohibited him who was smaller than all,106 because of his transgressions.

And what actually was his transgression, which prohibited him from building the house?

“You shed much blood, and it is not fitting,” says Scripture, “that you should build it.”107

The first blood was Goliath’s,108 and after him the Amalekites’.109

30 And yet not without God did he slaughter the former and the latter.

He would ask Him [sc. God], and then he would go up against the nation against whom he would rampage.110

His slaughter is less than that one who slaughtered the thirty-two kings.111

He did not shed blood among his people, except for the blood of Uriah,112pb. 292

And Uriah himself was Hittite and not Hebrew.113

35 He did not make a demand on Nabal due to his insult because Abigail beseeched him,114

And he had pity on Saul for the sake of God and Jonathan,115

He who spared his killer from the murder of the men who were with him,116

How was he unjust with regard to killing vainly the sons of his own nation?

Could it be that perhaps this same transgression stayed and remained until Nathan?

40 And that Nathan nullified his covenant in this way, when he said to him, “you will not build it.”117

But so that heaviness should not be compounded upon David’s body when he grew old,

He postponed his punishment after him, so that the old man would be in peace.

Kc‘urd 15 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 6]

Hymn of the Sixth Night

Why was David prevented from building the house? And whether it was because he shed much blood that [God] prohibited him.

1 If it was because David slaughtered the nations that it was not lawful [for him] to build the house,

Then everyone who slaughters like him, is under blame like him.

If that is so, then Abraham is blameworthy, who slaughtered the five kings,118pb. 293

And Moses who slaughtered Midian119 and Joshua who slaughtered Canaan.120

5 Asa is blameworthy who slaughtered the Indians,121 and Hesechiah who slaughtered Assyria,122

And the Maccabees who slaughtered Ionia,123 and Zerubbabel who slaughtered Macedonia.124

Yet if they are not blamed for the blood of those peoples which they shed,

Why is only David blamed because of this?

If the others were blameworthy, [God] would not let Moses fail to mention it.

10 Moses — he is great in reproaches, for he carries the reproaches of the rock.125

Moses slaughtered one of his people, and was not blamed.126

Neither was Elijah, who with his own hand slaughtered the prophets of Baal.127

Although Moses slaughtered the Hebrews, his face was radiant with glory.128

And Elijah who slaughtered the pagan priests, was taken up in a chariot to heaven.129pb. 294

15 To Jehu who slaughtered the prophets of Baal,130 [God] gave the equipment of the cult,

When [God] ordained that for four generations the crown be for his offspring.131

Yet David, who is equal with his companions, why did [God] discriminate him from his companions?

And if he did not discriminate him, then why did he deprive him of building the temple?

His companions received the good news, and for him [sc. David] a heap of murders.

20 Moses made the tent of meeting,132 but [God] prohibited him [sc. David] from building the house.

[God] did not deprive him on account of the nations, who were numbered among the holy ones,

But rather, [God] spared him from the hardship of the oath, by hastening to dissolve the oath.

If [David] had not hastened to swear, he would have built the temple.

The oath, which he swore on account of the temple — it deprived him of building it.

25 For he swore greater than his ability: that he would not enter into his house,

And that he would not go up to his bed, and that he would not give sleep to his eyes.133

Now so that he would not be in weariness until he had completed the structure

Before he even began the structure, [God] brought to fulfillment his oath by the prohibition.

[God] wanted to grant good things to him for the sakepb. 295 of his trustworthiness,

30 So [God] prohibited him under the guise of blame, since he [sc. David] is far from slander.

Because if on account of blame [God] would have prohibited him from building it,

Then Uriah would have been before Him [sc. God] to remind Him at that time.

But Uriah was nowhere to be found in order for [God] to remember, because David had been pardoned through Nathan.134

The blame of the righteous ones hastened to Him [sc. God], who surrounded Him [sc. God] and were not blamed.

35 Or was he who had received along with the temple the Spirit of holiness,135

And had been glorified and become worthy of the Spirit, was he unworthy to build the temple?

And if it was said to him in earnest, then why did [God] demand of him [sc. David]

That which was not demanded from a single one of the righteous?

And if all the righteous who had slaughtered — whether from the people or from the nations — were not blamed,

40 How could [God] have blamed David? On the contrary, he is blessed and without blame like his companions.

Kc‘urd 16 [Gišeroy kc‘urd 7]

Hymn of the Seventh Night

[Title and beginning lost]136pb. 296

1 …as the number of his years is prolonged.

Keeping watch, which is heavy for everyone, is very light for them.137

You are groomsmen, who were invited to the wedding of the groom who does not die.

Let us drive away sleep from our pupils through the blessing of our lips.

5 For if they become joyful there, by the joy that compunction gives to souls

How much more should they become joyful here, by the joy that gathers its seed a hundredfold!138

And if there — soundings of trumpets, here — harps of psalms;

There — accursed shoutings to the Evil One, while here — blessings to God.

There they repeat the hateful passions, which desire works among humankind,

10 While here they repeat the blessed passions, which the Lord and his servants bore.

For if through the trumpet and harp they remove sleep from the eyes of humans,

And if the clashing of cymbals dispels that which rebels against all [sc. sleep];

Then here, because the Spirit of holiness resounds in the mouth of David his harp,

How much more will wakefulness reign among us, so that through the power of his words we may become wise!pb. 297

15 If sleep, driven out by revelries, is defeated, and licentiousness was able to conquer it,

Then how much more will modesty conquer it!

The earthly139 groom becomes happy in watching140 instead of mourning;

The celestial141 groom becomes happy through the pure watching of holy mourners.

He who is defeated by the heavines of this sleep of limbs

20 Is reproached by the temporal groomsman who drove away sleep from his eyes.

There wakefulness is without recompense, and watching is without a promise,

But glory is prepared for our watching, and a paradise of delight is promised.

If in that watching there is festivity, behold, modesty in this watching.

And since that one is full of all harm, it is also thickened through slipping.

25 That watching passes, O brothers, yet all its stains are retained,

While although this watching ceases, the treasure of its life remains.

In the great dawning of the Son of God, the eternal groom,

They will expose the hidden sins, which were accumulated in the watching of the temporal groom.

Because there everyone is prepared to scandalize the one who listens to him,pb. 298

30 While here everyone is prepared to help the one who listens to him.

There everyone shows his face to his friend to harm him,

While here, behold through a veil, brothers have warned each other.

They summon desire upon themselves through the sound which enters their ears,

While here they hear the voice of the Spirit, who cleanses their minds.

35 There everyone is hardened to sin against his companion,

While here everyone strives to earn himself and his friend.142

There they go in revelry and laughter, while here they come in weeping and mourning.

The debts that they accumulated there, they expiate by this143 watching.144

If the watching that is full of such dangers is lovable and light,

40 Then how much more should our watching of manifold benefit be enjoyed by the sleepless ones!

Let us take for ourselves a good example from that licentious watching.

Let us resemble each other through wakefulness, but estrange ourselves from their thoughts.

And since their thoughts are similar to the exclamations that fall in their ears,

Our thoughts should be similar to the exclamations of the Spirit that we have heard.

45 The revelry ceased, but its harm remains; the watching passed, yet its lawlessness remains.pb. 299

Sayers and hearers died, but the judgement is kept for the awful tribunal.

We are one here and there, yet we are not equal; here, weary and dejected in mind;

For whatever is without benefit is light for the ones who do it,

While everything that comes about by hope, one performs with toil.

50 As the Evil One urges and hastens people to the watching that harms the watchers,

So also here he has his effect145 upon those who keep watch for the sake of benefit.

Commentary

The commentary will be limited to three major foci. First, I will provide evidence for a Syriac original to the Armenian text. Second, I will provide evidence for an early date of translation. Third, I will show how the teaching and practice of vigil in the Kc‘urdk‘ aligns with what we know about Ephrem’s views on vigil from the authentic Syriac works of Ephrem.

Prose far outweighs poetry in quantity in early Armenian literature, and early Armenian prose is indebted to ideals of Greek rhetoric for its compositional standards. Fifth-century Armenian prose is marked by balance and repetition in phraseology, lexical surplusage, complex syntactical constru-ctions, a prevalent use of compound verbal adjectives, and the use of rhetorical tropes and figures derived from Greek models. The Kc‘urdk‘ of Ephrem on the other hand are marked by simple syntactical constructions, lexical paucity, and an overall plain style of composition that owes little to Greekpb. 300 rhetorical models. Although they were originally composed in Syriac verse, the Armenian translator has made no consistent effort to render them into Armenian verse, apart from marking where the original Syriac lines ended. In the fifth century, Armenian poetic forms were still primarily oral and employed varying syllabic counts, and therefore were unlike the fixed syllabic counts of Ephrem’s verse forms.146 Concrete examples of linguistic evidence for a Syriac original are given below, first looking at phonology and then syntax and morphology.

The immediate place to look for evidence of a Syriac original in the realm of phonology is with the rendering of names in the texts. The vast number of names appearing in the Kc‘urdk‘ forbids bringing forth every example, but the examples drawn from the chart below are representative of the way that the translator often preserves a Syriac rendering of a name over and against a Greek one. The Armenian biblical text contains portions translated from both Greek and Syriac, and therefore names from biblical figures are rendered in the Armenian Bible as well as Armenian literature in different forms depending on whether they come from a Syriac or Greek original.147 Therefore, by looking at the names in the Armenian text, we can gain an indication as to whether the text issues from a Syriac or Greek original, based on how the translator renders the names.

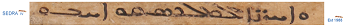

pb. 301| Name in English | Place in Text | Arm form from Syriac | Form in Syriac | Form in Greek | Arm form from Greek |

| Hoshea (a name of Joshua) | 10.21 [X.28]148 | Հոշայէ (gen.) | ܗܘܫܥ | Αυση | Աւսեայ (gen.) |

| Philistines | 12.18 [XII.31] | Փղշտացիք | ܦܠܫ̈ܬܝܐ | ὁι ἀλλόφυλοι | Այլազգիք149 |

| Saul | 12.27 [XII.47] | Շաւուղ | ܫܐܘܠ | Σαουλ | Սաւուղ |

| Joshua | 15.4 [XV.7] | Յեշով | ܝܫܘܥ | Ἰησοῦς | Յեսու |

| Jehu | 15.15 [XV.23] | Յահով | ܝܗܘ | Ιου | Յէու |

The Armenian versions of the names in the above chart all follow Syriac forms over and against the form in Greek, which provides strong evidence for the presence of a Syriac original. Although in a number of cases, the Armenian version of a name in the Kc‘urdk‘ follows a Greek form over and against a Syriac one, this can be explained by the fact that the former became predominant over time, and a translator or later copier would be more likely to prefer a Greek form to its Syriac variant, especially in the case of a common or renowned biblical figure. Conversely, the names of less common or renowned figures would have been more likely to retain their original form from the Syriac.150

pb. 302The syntax of the Kc‘urdk‘ exhibits throughout constructions that are unusual or awkward in Armenian grammar, because they are closely following an original Syriac. A number of representative examples will be brought forth below.

10.3 Բայց ի ժամէն, զի եղեւ նա աստուած[ատես] (But from the hour that he became a [seer of] god). In normal Armenian syntax, ի ժամէն զի would be rendered as ի ժամէն յորում, with the use of the relative pronoun in the locative. However, here it seems that the translator preferred to use the particle զի as it more closely matches with the Syriac ܕ, which is evidently the underlying form here.

10.7 [X.9]151 Դարձեալ կայր քունն Մովսիսի ի ներքս քան զնա (Although sleep was hovering near to Moses within it [sc. the veil]). Ի ներքս քան + զ + acc. is very awkward and unusual in Armenian. A more common Armenian rendering would be ներքոյ + gen. or ի ներքոյ + abl. It seems to be rendering an underlying Syriac ܠܓܘ ܡܢ. Armenian ի correlates with ܠ; ներքս correlates with ܓܘ; and քան correlates with ܡܢ.

10.43 [X.59] Նովին կշռով կերակրոյ իւրոյ կշռեաց զքուն աչաց իւրոց (By the same measure [with which he measured] his food, he measured the sleep of his eyes). Ellipsis is a prevelant feature of Syriac prose, when words or phrases may be supplied from corresponding clauses, as here.152 The same construction is not a regular feature of Armenian syntax.

11.29 [XI.45-46] Ժիրք որ վաստակին ի միջի մերում , նոքաւք կշտամբի վատութիւն մեր (The strong ones who toil among us, by them our laziness is reproached). The syntax of this phrase is unmistakeably Syriac, with its expansion, periphrasis, and use of antecedent and pronominal reference,pb. 303 the underlying portion being represented by something like: ܚܝܠܬܢ̈ܐ ܕ...ܒܗܢܘܢ where a fronted focused subject noun is introduced, then expanded into a relative by means of the pronoun ܕ, and then itself is the antecedent of a pronoun in the following phrase.153 Nothing like this is found in native Armenian writing.

11.35 [XI.57-58] Փառաւորի շունչ հսկեցողաց զբաղմամբ իւրեանց որ ընդ Աստուծոյ (The breath of watchers is glorified, through their occupation which is with God). There is nothing in the Armenian syntax which requires the use of the relative pronoun որ here, and it would read much smoother without it. However, it likely renders a Syriac ܕ, which in Syriac is preferable in the above construction.

11.31 [XI.51-52] Զի՞նչ աւգուտ է զի ննջեցաքն երէկ, զի յաւելցուք ննջեսցուք այսօր>։ (What benefit is it that we slept yesterday, since we will sleep again today?). In Syriac, the verb ܝܣܦ ‘to add, increase,’ when paired with another verb, takes on an adverbial function meaning ‘more’ or ‘again.’ In this line, the translator calqued the idiom into Armenian using the corresponding Armenian verb in this line, and again at 12.29 [XII.51-52]: եւ զի ոչ քասքնեաց նա յայնմանէ, եւ յաւել միւսանգամ ննջեաց (And because Saul did not shudder in fear from it [sleep], he continued and slept again).

12.28 [XII.49-50] ի ձեռն տտնոյն զոր եհատ, առ զթագաւորութիւնն ի նմանէ (Through the hem which he cut, he took the royal rule from him). Ի ձեռն + gen. to render an instrumental represents another calque of a Syriac idiom (ܒܝܕ). This idiom is used very frequently throughout the Kc‘urdk‘. While it is not uncommon in native Armenian due to influencepb. 304 most especially from the Bible (the LXX and NT also employ this Semitic construction), it is much more frequently found in Armenian translated from Syriac.

The above examples of Armenian syntactical and morphological usage closely following Syriac usage over and against standard Armenian syntactical practice are meant to serve as representative (and by no means exhaustive) examples, that provide strong evidence for a Syriac original to the Kc‘urdk‘.

Certain syntactic features in the Kc‘urdk‘ are also indicative of early Armenian usage. Two representative examples are presented below.

12.32 [XII.57-58]154 Զի յայնմ քնոյ որ յայրի անդ, քուն յաւիտենից ննջեաց նա (For after that sleep which was in the cave, he slept an eternal sleep). This line has two features characteristic of early Armenian prose. The first is the use of the local adverb (անդ) in the place of the deictic suffix (-ն) to define the object of the preposition ի (when used with a sense of motion).155 In later periods of Armenian, the deictic suffix is more commonly used to define the object in these kinds of grammatical constructions. The second feature here is the otiose usage of the personal pronoun (նա), which in constructions like the above clause is perceived by later Armenian writers to be redundant and tends to be dropped, since there is no change of subject (and third person singular is indicated already by the verb ending). In early Armenian prose however, there is a greater tendency for an otiose use of personal pronouns. Another example may be found in 12.41 [XII.75-76]: Զի այն որ ննջէն հանդերձ արթնովն մի են եւ չեն մի նոքա (Because he who sleeps along with the wakeful one, they are one, and they are not one).

The most important linguistic feature of the Kc‘urdk‘ suggesting an early date of translation lies in the realm of morphology. Rather than specific data, it is the lack of data — that is, the striking absence of any influence from the Hellenizing school of translations, which began in the sixth century and affected the morphology of all later Armenian authors and translators to a greater or lesser extent.156 The absence of any influence from the Hellenizing school of translations strongly suggests that the translation of the Kc‘urdk‘ was made before the sixth century.

Early Armenian Christianity bears witness to Syriac, and in particular Edessene influence, in a variety of areas. These include of course liturgical practices, such as a pre-baptismal anointing (prior to the invention of Armenian letters, Syriac was the liturgical language of certain spheres in the Armenian realm and so the maintenance of specifically Syriac liturgical practices is by no means surprising).157 Influence is also seen in myths of apostolic foundation, where there was for example a co-opting of the Abgar legend, that turned Abgar into an Armenian king, and the apostolic mission of Addai/Thaddaeus into the realm of Armenia. Syriac influence is also prevelant in other realms of literature and language (particularly in vocabulary in the ecclesiastical domain). Koriwn, the disciplepb. 306 and biographer of Maštoc‘, inventor of the Armenian alphabet, narrates how his master went first to Edessa in his quest to create an alphabet for Armenian, making use of a modified Syriac alphabet for two years before developing the Armenian alphabet. Armenian students were also sent to Edessa to study Syriac so as to be able to translate from Syriac into Armenian. It is then by no means surprising that in the fifth-century translation efforts, Maštoc‘ and his students drew on the works of Ephrem, who besides being renowned in Edessa, had gained fame across the multilingual Christian world, including of course the Armenian realm with its strong Syriac influence.

The topics treated in these particular Kc‘urdk‘ also fit well with what we know of the interests and the particular ascetic inclinations of Maštoc‘ and his students, which shared much in common with early Syriac asceticism, as can be seen in the works of Koriwn and the Buzandaran (P‘awstos Biwzand), and thus it is easy to see why they would have been objects of translation.158 Finally, the Kc‘urdk‘ show no signs of any Christological or Theological language or concepts dating from a period after the fourth century, nor any other historical references after the time of Ephrem. After considering the historical situation, one is led to conclude that it would be much more surprising if the Armenian tradition did not transmit authentic works of Ephrem the Syrian than if it did.

If these texts then are authentic, it seems more likely that they were translated in an early period rather than in the medieval period, since no Syriac originals survive, not even in fragmentary form. A counter argument cannot be made from the fact that the earliest extant manuscript of the Kc‘urdk‘ dates from the thirteenth century, since so few Armenian manuscripts survive from before the tenth century.159 Thepb. 307 earliest Armenian manuscripts of many renowned early authors — both native Armenian authors and translated authors of an early period — date from the thirteenth century or later.

In this section, a brief discussion will be advanced to suggest that the teaching and practice of vigil as presented in the Kc‘urdk‘ align with the views on vigil that are presented in Ephrem’s authentic Syriac corpus.

Ephrem speaks of vigil and watching not as actions undertaken only by human beings, but as something proper to the divine and angelic realms as well. In the divine realm, Christ is presented as the watcher par excellence, and even referred to as such by that appellation; for example, one of the Hymns on Nisibis is a meditation on Christ the watcher, who descended to Sheol after his crucifixion to awaken the sleepers there.160 In a dense passage from the Commentary on the Diatessaron referring to Christ’s calming of the storm at sea, Ephrem writes: “He who was sleeping was awakened, and put to sleep the sea, so that by the wakefulness of the sea which had slept, he mightpb. 308 demonstrate the wakefulness of his divinity, which never sleeps.”161 Ephrem likely drew inspiration from the biblical image of God as the one who never sleeps, constantly keeping watch over his creation.162 Jesus shares in this quality through his divinity which remained “awake” in him even during the incarnation, and hence he is referred to as the “watcher” or “wakeful one.” We find this same teaching in the Kc‘urdk‘, most prominently in the latter half of Kc‘urd 13 (lines 26-38), where Ephrem discusses the purpose of Christ’s watching.

An important aspect of the mission of Christ the watcher was to come to earth to wake up human creatures, lost in the slumber of sin. In the Hymns on Nativity, Ephrem writes, “Let us glorify Him Who watched and put to sleep our captor. / Let us glorify the One Who went to sleep and awoke our slumber.”163 The need for human beings to be awakened from their slumber is present in other early Syriac literature, such as the famous Hymn of the Pearl.164 In a later hymn from this same cycle, Ephrem writes: “The Watcher has come to make us watchers on earth.”165 But why the need to watch? In Early Christianity, watching and vigilance had an eschatological reference, involving the anticipation of the Second Coming. The parable of the ten virgins is crucial here. When the bridegroom came, those invited to the banquet would be those who had stayed awake to watch for his coming. Hence, the constant reiteration of the importance of keeping watch, during the four watches of the night, since it is during one of those watches that Christ indicated he will return, as is expressed in Kc‘urd 11.9-13.

pb. 309Watchfulness is also a practice associated with the angelic realm. This is due in part to the fact that watchfulness is associated with holiness and thus bears easy connection with the sinless angels, whereas, by contrast, insentient sleep is associated with death and sin. This dichotomy of wakeful-ness/holiness and sleep/sin is made explicit in the first Hymn on the Nativity:

The watchers rejoice today because the Awakener has come to wake us up; Who will sleep on this night when all creation is awake? Because Adam introduced into the world the sleep of death in sins, The Watcher came down to wake us up from the slumber of sin.166The purpose of Christ’s coming into the world, as celebrated in the feast of the Nativity, is to wake up humans from the slumber induced by sin. Kc‘urd 13.18-21 also makes explicit mention of the host of angels keeping vigil on the night of Christ’s birth. In the first line of the above quoted text, the angels are referred to explicitly as “watchers.” In fact, “watchers” (‘īre) is one of Ephrem’s most frequent designations for angelic beings, and appears throughout his Syriac corpus; this Aramaic appellation for angels is common to both Jewish and Syriac Christian tradition, and goes back all the way to the biblical book of Daniel.167 Armenian shares thispb. 310 usage, with its term զուարթունք (zuart‘unk‘, “sleepless ones”), used in the Kc‘urdk‘ to refer to angels.168 Like Christ, “watchers” are sleepless, since they stand ceaselessly in the divine presence in perpetual contemplation and praise, and as such serve as models of admiration and imitation. They maintain the continual consciousness of attention on God that the human watcher strives for through the practice of vigil. The watching of angels is twofold, as they stand wakeful not just in God’s presence, but also watch over earthly life, as Ephrem puts it “suffering over the sinners but rejoicing over penitents.”169

Watchfulness is closely associated with another concept important to Ephrem and early Syriac Christianity, that of íḥiyḍāyā, a term rich in semantic range, incorporating at least three separate but interconnected fields of meaning: singular, unique, individual; single-minded, not divided in heart; and single in the sense of unmarried, celibate.170 The term in its first usage refers above all to Christ, and corresponds to Greek monogenēs, “only-begotten.” Its connection with watching and vigil is particularly relevant in the second range, that of single-mindedness, in other words not being divided in heart or will.pb. 311 To be watchful is to be in spiritual harmony, to be always attentive and single-minded in one’s devotion to Christ.171 It is to maintain a consistent consciousness of attention on God in prayer. This understanding of being single and undivided in conscious vigil and being divided in sleep occurs in the Kc‘urdk‘ as well.172 It also helps one understand the negative portrayal of the creation of Eve during the sleep of Adam in Kc‘urd 12.3-4.

Not all watching is portrayed positively in the works of Ephrem. There are forms of watching that not only are of no benefit but are harmful, such as the vigil of the greedy who stay up late to devise ways to make more money or the worrier who cannot sleep from the anxiety brought on by worries.173 Referring to biblical examples, Ephrem says that even Judas Iscariot kept vigil an entire night to betray Christ, and “even the Pharisees, sons of darkness, were awake an entire night; / the dark ones kept vigil to conceal the incomprehensible light.”174 Similarly, Kc‘urd 16 contains a lengthy meditation on the worthlessness of those who stay up late “keeping vigil” at a wedding party. This stands in sharp contrast with the benefits accrued by those who keep vigil in anticipation of the heavenly bridegroom.

This brief discussion indicates the consonance of Ephrem’s thought on vigil as expressed in the Kc‘urdk‘ with what we know from the authentic Syriac texts of Ephrem that mention vigil, further reinforcing the linguistic and historical evidence that point to the strong likelihood of the Kc‘urdk‘ being authentic works authored by Ephrem, and translated in the fifth century.

pb. 312Bibliography

- Akinian, Nersēs, Kc‘urdk‘ S. Ep‘remi Xorin Asorwoy [=Ephräm des Syrers 51 Madrasche in Armenischer Ubersetzung], Texte und Untersuchungen der Altarmenischen Literature, Bd. 1.3 (Vienna, 1957).

- _____, Ts‘uts‘ak hayerēn dzeragrats‘ Nikosiayi i Kipros [=Katalog der armenischen Handscriften in Nikosia auf Cyprus], Vienna, 1961.

- Beck, Edmund, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Fide, 4 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 154–5; 212–13 (Louvain 1955; 1961).

- _____, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen contra Haereses, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 169/170, Scriptores Syri 76/77 (Louvain, 1957).

- _____, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen de Paradiso und Contra Julianum, 2 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 174–5 (Louvain 1957).

- _____, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen De Nativitate (Epiphania) 2 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 186–7 (Louvain, 1959).

- _____, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Carmina Nisibena, 4 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 218–9, 240-241 (Louvain, 1961; 1963).

- _____, “Ephräms des Syrers Hymnik,” in Liturgie und Dichtung. Ein interdisziplinäres Kompendium. Gualtero Duerig annum vitae septuagesimum feliciter complenti, eds. H. Becker and R. Kaczynski (St. Ottilien, 1983), vol. 1: 345-379.

- Boyce, Mary, “The Parthian ‘Gōsān’ and Iranian Minstrel Tradition,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1/2 (April 1957): 10-45.

- Brock, Sebastian, The Luminous Eye: The Spiritual World Vision of Saint Ephrem, Cistercian Studies Series 124 (Kalamazoo, 1992).

- _____, The Harp of the Spirit: Poems of Saint Ephrem the Syrian, 3rd ed., The Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies (Cambridge, 2013).

- Butts, Aaron, “The Classical Syriac Language,” in The Syriac World, ed. Daniel King (Routledge, forthcoming in 2018).

- Cassingena-Trévedy, François, o.s.b., Hymnes sur la nativité, Sources Chrétiennes 459 (Paris, 2001).

- Cerbelaud, Dominique, La descente aux enfers: Carmina Nisibena, Spiritualité Orientale 89 (Godewaersvelde, 2009).

- Cowe, S. Peter, “The Two Armenian Versions of Chronicles: their Origin and Translation Technique,” Revue des études arméniennes 22 (1990–1): 53–96.

- _____, “The Bible in Armenian” in The New Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 2: From 600 to 1450, eds. Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter (Cambridge, 2012): 143-161.

- den Biesen, Kees, Simple and Bold: Ephrem’s Art of Symbolic Thought, Gorgias Dissertations 26, Early Christian Studies 6 (Piscataway, NJ, 2006).

- Eganyan, Ō., A. Zeytʻunyan, Pʻ. Antʻabyan, eds., Mayr tsʻutsʻak hayerēn dzeṛagratsʻ Mashtotsʻi Anuan Matenadarani [=Grand Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran named Maštoc‘], 9 vols., Erevan, 1984—.

- Ełišē Vardapet, Matenagrut‘iwnk‘, Venice, 1859.

- Féghali, P., and C. Navarre, Saint Éphrem: Sur les chants de Nisibe, Antioche chrétienne 3 (Paris, 1997).

- Garsoïan, Nina, “Introduction to the Problem of Early Armenian Monasticism,” Revue des études arméniennes 30 (2005-7): 177-236.

- Goldenberg, Gideon, “On Some Niceties of Syriac Syntax” in Studies in Semitic Linguistics: Selected Writings (Jerusalem, 1998): 579-590.

- Graffin, François, “Hymnes inédites de S. Ephrem sur la virginité” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 213–42.

- Kouymjian, Dickran, “The Archaeology of the Armenian Manuscript: Codicology, Paleography, and Beyond,” in Armenian Philology in the Modern Era: From Manuscript to Digital Text, ed. Valentina Calzolari (Leiden, 2014): 5–22.

- Lange, Christian, The Portrayal of Christ in the Syriac Commentary on the Diatessaron, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 616, Subsidia 118 (Louvain, 2005).

- Maier, Carmen, “Poetry as Exegesis: Ephrem the Syrian’s Method of Scriptural Interpretation Especially as Seen in his Hymns on Paradise and Hymns on Unleavened Bread,” PhD diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 2012.

- Mariès, Louis, “Une Antiphona de Saint Ephrem sur l’eucharistie,” Recherches de Science Religieuse 42 (1954), 395-403.

- _____, “Deux Antiphonae de Saint Ephrem,” Recherches de Science Religieuse 45 (1957), 396-408.

- Mariès, Louis and Charles Mercier, Hymnes de Saint Ephrem conservées en version arménienne, Patrologia Orientalis XXX, fascicle 1 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1961).

- Mathews, Edward, “Armenian Hymn IX, On Marriage by Saint Ephrem the Syrian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 9 (1996/7 [1999]): 55-63.

- _____, “Saint Ephrem the Syrian: Armenian Dispute Hymns between Virginity and Chastity,” Revue des études arméniennes 28 (2001/2): 143–69.

- _____, “Syriac into Armenian: The Translations and their Translators,” Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 10 (2010): 20-44.

- McVey, Kathleen, Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns (New York, 1989).

- _____, “Were the earliest madrāšē songs or recitations?” in After Bardaisan. Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J.W. Drijvers, eds. G.J. Reinink and A.C. Klugkist, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89 (Louvain, 1999): 185-199.

- Muradyan, Gohar, Grecisms in Ancient Armenian, Hebrew University Armenian Studies 13, (Leuven, 2012).

- Muraoka, Takamitsu, Classical Syriac: A Basic Grammar with a Chrestomathy, 2nd rev. ed., Porta Linguarum Orientalium: Neue Serie (Wiesbaden, 2005).

- Murray, Robert, “The Origin of Aramaic ‘îr, Angel,” Orientalia 53 (1984): 303–317.

- _____, “‘A Marriage for all eternity’: The Consecration of a Syrian bride of Christ,” Sobornost/Eastern Churches Review 11 (1989): 65–8.

- _____, “Some Themes and Problems of Early Syriac Angelology,” Orientalia Christiana Analecta 236 (1990): 143–153.

- _____, “Aramaic and Syriac Dispute-Poems and Their Connections,” in M.J. Geller, J.C. Greenfield, M.P. Weitzmann, eds., Studia Aramaica: New Sources and New Approaches, Journal of Semitic Studies, Supplement 4, (Oxford, 1995): 157-187.

- _____, Symbols of Church and Kingdom: A Study in Early Syriac Tradition, rev. ed. (Piscataway, 2004).

- Nöldeke, Theodor, Compendious Syriac Grammar, tr. James A. Chrichton (London, 1904).

- Outtier, Bernard, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie,” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes 18 (avril-juin 1979): 3-9.

- _____, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie II” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes 22 (avril-juin 1980): 3-8.

- _____, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie III” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1981:1): 14-18.

- _____, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie IV” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1981:3): 3-7.

- _____, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie V” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1982:2): 3-5.

- NBHL = Nor bargirk‘ haygazean lezui, 2 vols. (Venice 1836-7).

- Palmer, Andrew, “A Single Human Being Divided in Himself: Ephraim the Syrian, the Man in the Middle,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 1:2 (1998): 119-163.

- _____, “Ephrem of Nisibis,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Patristics, ed. Ken Parry (Chichester, 2015): 126–140.

- Poirier, P. H., L'hymne de la perle des actes de Thomas. Introduction, Texte-Traduction, Commentaire, (Louvain-la-Neuve, 1981).

- Tanielian, Anoushawan Vardapet, Mayr tsʻutsʻak hayerēn dzeṛagratsʻ Metsi Tann Kilikioy Katʻoghikosutʻean [=Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts in the Collection of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia], (Antelias, 1984).

- Terian, Abraham, “The Hellenizing School: Its Time, Place, and Scope of Activities Reconsidered” in East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the Formative Period (Dumbarton Oaks Symposium, 1980), eds. Nina Garsoïan, Thomas F. Mathews, and Robert W. Thomson (Washington, D.C., 1982): 175-186.

- Tēr-Petrosian, Levon, “Kc‘urdk‘ S. Ep‘remi Xorin Asorvoy: Bnagrakan Čšgrtumner [Kc‘urdk‘ of Ephrem the Syrian: Text-Critical Emendations],” Handēs Amsoreay 92 (1978): 15-48.

- Wickes, Jeffrey T., “Out of Books, a World: The Scriptural Poetics of Ephrem the Syrian’s Hymns on Faith,” PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2013. .

- _____, St. Ephrem the Syrian. The Hymns on Faith, The Fathers of the Church 130 (Washington D.C. 2015).

Footnotes

1 I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Peter Cowe, for his close guidance throughout the process of writing and revising this article and the translations therein, which was carried out in the course of a year-long seminar on Armenian Ephremica at UCLA. This article and the translations would have been much poorer without his careful and thorough assistance. I would also like to thank Jeffrey Wickes, who, both via email and in person at the 2017 NAPS meeting (where an earlier version of this paper was presented), offered suggestions and helped me with some of my questions regarding Ephrem and his fourth-century context, while pointing me to relevant bibliographical sources that I made use of in this paper. All shortcomings in this article and any errors in translation are entirely my own responsibility. A note on transliteration: Armenian has been transliterated according to the Hübschmann-Meillet standard as applied in the Revue des Études Arméniennes, and Syriac has been transliterated according to the standard used by the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/roman.html. Accessed 20 March 2018). This has not been strictly maintained for the names of modern Armenian writers, in cases where their names are conventionally rendered into Latin characters with a different spelling, or for bibliographic references classified according to a different transliteration system (such as Library of Congress). For the vowel ու, I follow the convention of transliterating it as ‘u’ instead of ‘ow.’ Thus: կցուրդ is rendered as kc‘urd and not kc‘owrd. Transliterated words in both languages are marked off in italics, except for personal and place names.

2 This is the nomenclature of scholars such as Andrew Palmer and Kees den Biesen. See Andrew Palmer, “A Single Human Being Divided in Himself: Ephraim the Syrian, the Man in the Middle,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 1:2 (1998): 119-163; Kees den Biesen, Simple and Bold: Ephrem’s Art of Symbolic Thought, Gorgias Dissertations 26, Early Christian Studies 6 (Piscataway, NJ, 2006).

3 On the madrāšā genre, see Kathleen McVey, “Were the earliest madrāšē songs or recitations?” in After Bardaisan. Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J.W. Drijvers, eds. G.J. Reinink and A.C. Klugkist, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89 (Louvain, 1999): 185-199; Edmund Beck, “Ephräms des Syrers Hymnik,” in Liturgie und Dichtung. Ein interdisziplinäres Kompendium. Gualtero Duerig annum vitae septuagesimum feliciter complenti, eds. H. Becker and R. Kaczynski (St. Ottilien, 1983), vol. 1: 345-379.

4 Hymns against Heresies 53.5.1-5 in Edmund Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen contra Haereses, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 169/170, Scriptores Syri 76/77 (Louvain, 1957). See Kathleen McVey, “The earliest madrāšē,” 187-188.

5 On Ephrem’s theological method, see den Biesen, Simple and Bold, as well as two recent dissertations: Jeffrey Wickes, “Out of Books, a World: The Scriptural Poetics of Ephrem the Syrian’s Hymns on Faith,” PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2013; Carmen Maier, “Poetry as Exegesis: Ephrem the Syrian’s Method of Scriptural Interpretation Especially as Seen in his Hymns on Paradise and Hymns on Unleavened Bread,” PhD diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 2012.

6 On the performance context of Ephrem’s madrāše, see Andrew Palmer, “Ephrem of Nisibis,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Patristics, ed. Ken Parry (Chichester, 2015): 126–140 at 127.

7 NBHL, s.v. կցուրդ.

8 It likewise carries a derivative meaning of “to play (an instrument)” or “to sing.” See NBHL, s.v. կցեմ.

9 NBHL, s.v. շարական, շարեմ.

10 Nersēs Akinian, Kc‘urdk‘ S. Ep‘remi Xorin Asorwoy [=Ephräm des Syrers 51 Madrasche in Armenischer Ubersetzung], Texte und Untersuchungen der Altarmenischen Literature, Bd. 1.3 (Vienna, 1957).

11 Louis Mariès and Charles Mercier, Hymnes de Saint Ephrem conservées en version arménienne, Patrologia Orientalis XXX, fascicle 1 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1961). For earlier publications see Edward Mathews, “Armenian Hymn IX, On Marriage by Saint Ephrem the Syrian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 9 (1999): 55-63, at 56-57, n. 7; and Mariès and Mercier, Hymnes, 10-11.

12 Levon Tēr-Petrosian, “Kc‘urdk‘ S. Ep‘remi Xorin Asorvoy: Bnagrakan Čšgrtumner [Kc‘urdk‘ of Ephrem the Syrian: Text-Critical Emendations],” Handēs Amsoreay 92 (1978): 15-48.

13 The following kc‘urdk‘ have been translated into English or French: Kc‘urdk‘ 2-7, 9 in François Graffin, “Hymnes inédites de S. Ephrem sur la virginité” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 213–42; Kc‘urdk‘ 4-5 in Edward Mathews, “Saint Ephrem the Syrian: Armenian Dispute Hymns between Virginity and Chastity,” Revue des études arméniennes 28 (2001/2): 143–69; Kc‘urd 9 in Edward Mathews, “Armenian Hymn IX, On Marriage, by Saint Ephrem the Syrian,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 9 (1996/7 [1999]): 55–63; Kc‘urdk‘ 14-15 in Louis Mariès, “Deux Antiphonae de Saint Ephrem,” Recherches de Science Religieuse 45 (1957), 396-408; Kc‘urd 46 in Robert Murray, “‘A Marriage for all eternity’: The Consecration of a Syrian bride of Christ,” Sobornost/Eastern Churches Review 11 (1989): 65–8; Kc‘urdk‘ 47-51 in Bernard Outtier, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie,” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes 18 (avril-juin 1979): 3-9 and Idem, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie II” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes 22 (avril-juin 1980): 3-8 and Idem, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie III” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1981:1): 14-18 and Idem, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie IV” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1981:3): 3-7 and Idem, “Hymnes de saint Ephrem sur l’Eucharistie V” Lettre aux amis de Solesmes (1982:2): 3-5; Kc‘urd 48 in Louis Mariès, “Une Antiphona de Saint Ephrem sur l’eucharistie,” Recherches de Science Religieuse 42 (1954), 395-403; Kc‘urd 49 in Sebastian Brock, The Harp of the Spirit: Poems of Saint Ephrem the Syrian, 3rd ed., The Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies (Cambridge, 2013): 119-123. Robert Murray also treats the dispute hymns (Kc‘urdk‘ 4-5, 9) in Robert Murray, “Aramaic and Syriac Dispute-Poems and Their Connections,” in M.J. Geller, J.C. Greenfield, M.P. Weitzmann, eds., Studia Aramaica: New Sources and New Approaches, Journal of Semitic Studies, Supplement 4, (Oxford, 1995): 157-187.

14 Akinian, Kc‘urdk‘, ix-xviii and Mariès and Mercier, Hymnes, 8-18. I summarize their description of the manuscripts in my account which follows, also making use of Ō. Eganyan, A. Zeytʻunyan, Pʻ. Antʻabyan, eds., Mayr tsʻutsʻak hayerēn dzeṛagratsʻ Mashtotsʻi Anuan Matenadarani [=Grand Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts of the Matenadaran named Maštoc‘], Erevan, 1984—, vol. III, s.v. 821. In fact, for Kc‘urdk‘ 16-51, Akinian actually uses Vienna 257 as his base text, which is a derivative of Matenadaran 821.

15 Eganyan et al., Mayr tsʻutsʻak, vol. III, s.v. 821. The full texts of the Matenadaran manuscript catalogues (now up to nine volumes, which covers manuscripts 1-3000) are available at the Matenadaran website: http://www.matenadaran.am/.

16 The full colophon of the renewer reads as follows: Ի թվին ՌԽԵ (1596) ամին նորոգեցաւ դարձեալ վերստին սուրբ գիրքս ի գեաւղաքաղաքն ի Թլկուրան, ի դուռն Սուրբ Կարապետին, ի հայրապետութեան տէր Պետրոս քաջ րաբունապետին մերոյ, եւ ի առաջնորդութեանն տէր Կարապետին եւ աստուածաբան վարդապետին, ձեռամբ անարժան Թումայի աշակերտի։ Եւ որք ընթեռնուք եւ ուսանիք, Աստուած ողորմի ասացէք, եւ Աստուած ձեզ եւ մեզ ողորմեսցի. ամէն։ Դարձեալ, կրկին, աղաչեմ, չլինել մեղադիր մեզ վասն պակասութեան գրոցս եւ խարնիխուրն լինելոյ, քանզի յոյժ աշխատ եղաք եւ ոչ կարացաք գտանել զպակասն սորա, եւ այլ օրինակ ոչ գոյր, բայց զայն, որ յայտնի գոյ ի գիրքս՝ ուսցիս եւ զմեզ անպարսաւ թողցես. եւ Քրիստոսի փառք յաւիտեանս. ամէն։ In the year 1045 (=1596 CE) this holy book was yet again restored in the town of T‘lkuran, at the door of Holy Karapet, during the patriarchy of Father Petros our excellent pontiff, and during the prelacy of Father Karapet, theological doctor [vardapet], by the hand of the unworthy disciple T‘umay. And you who read and study it, say “May God have mercy,” and may God have mercy upon you and us. Amen. Again, a second time, I beg you not to blame us on account of the defectiveness of this book and its mixed-up state, because we made great effort and yet were unable to find its missing pages, and there was no other exemplar, except that which is present in this book. May you study, and leave us irreproachable. And to Christ glory forever. Amen. Eganyan et al., Mayr ts‘uts‘ak, vol. III, s.v. 821.

17 Nersēs Akinian, Tsʻutsʻak hayerēn dzeragratsʻ Nikosiayi i Kipros [=Katalog der armenischen Handscriften in Nikosia auf Cyprus], Vienna, 1961, 36-41. The manuscripts of Nicosia, Cyprus are now held in Antelias, Lebanon at the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. Nicosia 8 is now Antelias 85, and is also described in Anoushawan Vardapet Tanielian, Mayr tsʻutsʻak hayerēn dzeṛagratsʻ Metsi Tann Kilikioy Katʻoghikosutʻean [=Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts in the Collection of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia], (Antelias, 1984), 319-322.

18 For example, according to Edward Mathews, “Language, style, and the themes treated in these poems clearly reflect those found in the genuine Syriac hymns of Ephrem,” in Mathews, “Armenian Dispute Hymns,” 148. Robert Murray, in the brief introduction to his translation of Kc‘urd 46 says, “Though this poem comes to us in Armenian, a number of significant expressions clearly represent Syriac terms which are familiar both from St. Ephrem and from his contemporary Aphrahat,” in Murray, “Marriage for all eternity,” 65. For further examples, see the studies in note 10 above.

19 On the dating and authorship of Syriac translations into Armenian, see Edward G. Mathews, “Syriac into Armenian: The Translations and their Translators,” Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 10 (2010): 20-44.

20 I am following the text found in Mariès and Mercier, Hymnes, 76-80, which is the same as that of Akinian, Kc‘urdk‘, 26-28. Since this is a diplomatic edition, at times I translate from more preferable readings found in the apparatus or among the additional manuscript witnesses found in Tēr-Petrosian, “Kc‘urdk‘.”

21 The following account of Moses’ behavior on Mount Sinai differs in many respects from the narrative in Exodus (which commences in chapter 19 and continues to the end of the book). Ephrem likely makes use of extracanonical, including oral traditions native to early Syriac Christian and perhaps Rabbinic traditions of Mesopotamia related to Moses, as he expands the biblical narrative with his own interpretation. This is of course one of the aspects of the poetic, exegetical method of his madrāše that align them with their Hebrew counterpart, midraš.

22 The text reads reads simply աստուած (“god”). Akinian suggested correcting աստուած to աստուածատես (“a seer of God”). Although there are no manuscript witnesses to support his emendation, it is logically sound and I have followed it in the English translation. The compound աստուածատես (“a seer of God”) is found among fifth-century writers. See NBHL, s.v. աստուածատես.

23 Literally, “clothed, dressed” (զգեցան).

24 Exod 34:29-35.

25 Ephrem derives the number eighty by combining the two accounts of Moses being on the mountain for forty days and forty nights, as mentioned in Exod 24:18 and Exod 34:28.

26 Literally, “clothed, dressed” (զգեցաւ).

27 Literally, “lower (ներքին) and not upper (վերին).”

28 Ephrem is referring to Moses’ appearance at the transfiguration. See Matt 17:1-8 with parallels in Mark 9:2-8 and Luke 9:28-36.

29 The subjectless “ասէ” in the Armenian text is usually used to introduce a quote from Scripture, although here it could refer to Tradition more broadly, or an early written or oral souce that falls outside of canonical Scripture.

30 None of the gospel passages mention directly Moses’ lack of sleep, so presumably Ephrem is drawing on an extra-canonical source. The Lukan account does mention the disciples sleepiness during the event. Ephrem seems to distinguish in this passage between two kinds of sleep: one that is lower (terrestrial) and one that is upper (celestial). The latter is a kind of intelligible, cognizant sleep of eternal rest.

31 Joshua is regularly named along with his patronymic, since the Syriac for Joshua and Jesus are the same (as in Hebrew and Greek). The form found in the Armenian bible for “Joshua, Son of Nun” is normally Յեսու որդի Նաւեայ , as in Exodus 33:11, Numbers 11:28, 13:16/17, Joshua 1:1, and elsewhere. The unusual form here (Յեսու Նաւեանց ) is a kind of Armenization of the patronymic, treating it gramatically how Armenian naxarar family names are treated. The same form is also found in the beginning of a commentary on Joshua and Judges by the fifth-century author Ełišē (Մեկնութիւն Յեսուայ եւ Դատաւորաց): “Կոչեցաւ Յեսու Նաւեանց ի Տեառնէ առաջնորդ Իսրայելի ...” in Ełišē Vardapet, Matenagrut‘iwnk‘, Venice, 1859, 167.

32 Exod 33:11.

33 Hoshea was the name of Joshua before Moses changed his name: see Num 13:8 and Num 13:16/17. The Armenian form here (Հոշայէ) is derived from the Syriac (hušā‘ ), and not from the Greek (Αυση), even though the form found in the Armenian bible (Աւսեայ, appearing only in the genitive) is derived from the Greek.

34 1 Kgs 19:8.

35 1 Kgs 19.

36 This seems to be another allusion to the transfiguration, as was made with Moses above.

37 Job 1:20-22; 2:9-10.

38 Jonah 1:17-2:10.

39 Jonah 1:3.

40 Jonah 2.

41 Jer 38:6-13.

42 Ezek 4:4-8.

43 Ezek 4:9-17.

44 The language here of “a little while” hearkens to Jesus’ farewell discourse in the gospel of John (see John 16:16). Immediately following this discourse is the incident at Gethsemane, where Jesus tells the disciples to watch and they fall asleep. This is brought up in the verses of this Kc‘urd that immediately follow. Thus, Ephrem encourages his watchers not to fall asleep as the disciples did.

45 Matt 26:36-46 with parallels in Mark 14:32-42, Luke 22:40-46.

46 This appears to be a reference to the parable of the bridegroom, although this exact language is not found in the gospel passages (see Matt 25:1-13). Ephrem may also have in mind Mark 13:32-37.

47 The four watches of the night are mentioned in Mark 13:35 (evening, midnight, cockcrow, and dawn).

48 Mark 13:32-37.

49 Ephrem’s point is that even if the Second Coming does not occur in their days, they will still get a reward for having kept watch.

50 This doesn’t seem to correspond to any canonical biblical passage, so it likely derives from an extra-canonical source.

51 For thunder, lightning, and other celestial activity in regards to the return of Christ, see Matt 24: 27-31 and Luke 17:24.

52 Matt 24:29.

53 Matt 24:30.

54 Ephrem here seems to envision a vigilance enveloping everyone and everything. This vigilance is single and whole, and will continue without ceasing, allowing for a pure continuity of consciousness. On animals keeping watch, see for example the reference to the wild beasts keeping watch with Daniel in the den at Kc‘urd 13.2.

55 Following mss C: պահէ instead of պատմէ.

56 ծանրարթունք, literally “heavily-awake,” perhaps a reference to keeping watch in a hypnagogic state.

57 Ephrem indicates that his group keeping watch is not the most extreme ascetically, keeping vigil as they do for around half the night. There are others who shun sleep even longer, keeping watch throughout the entire night.

58 Here begins a contrast between the praying of watchers and the dreaming of sleepers. Dreams are regarded as empty and evanescent at best, with the dangerous potential to induce passions and sin through deceptive and foul visions (dreams). Furthermore, there is no lasting benefit brought from sleep or its attendant dreams, as one simply becomes tired again the next day. Watching with prayer on the other hand, brings both present and lasting benefit to the practitioner, purifying them in and through the act of watching, while storing up future benefits and recompense that will be reaped at the revelation of Christ.

59 This section likely serves as a warning to those of Ephrem’s community who have skipped the vigil for sleep (or were tempted to do so).

60 The very communal idea expressed here and alluded to also in verse 1 of this Kc‘urd is that those keeping watch lift the heaviness for those who did not keep vigil. On the idea of the vigil of some making up for the neglect or sin of others, see also Kc‘urd 16.38.