The Mêmrâ on the Signs Moses Performed in Egypt

An Exegetical Homily of the "School" of Ephrem*

This article examines the Mêmrâ on the Signs Moses Performed in Egypt, a text first published by J.J. Overbeck. Despite its attribution to Ephrem of Nisibis (ca. 307–373), this mêmrâ is not well-known in Syriac scholarship. In this article, I provide the first English translation of the text, and argue that it is the product of the literary circle of Ephrem in fourth-century Nisibis or Edessa. Furthermore, I contend that this prose exegetical homily represents a genre almost entirely unknown in extant early Syriac literature. As a witness to little-known exegetical and homiletical practices in that formative period, it enriches our understanding of the early emergence and development of Syriac Christian literary culture.

PART I: THE MÊMRÂ ON THE SIGNS AND SYRIAC LITERARY CULTURE IN THE FOURTH CENTURY

Although scholars widely acknowledge Ephrem of Nisibis (ca. 307–373) as a singular figure in Syriac literature and a valuable source for Christianity in late antique Northern Mesopotamia, many texts bearing his name remain untranslated and unstudied. Among the vast corpus of little-known Syriac texts attributed to Ephrem is a prose mêmrâ entitled “First Mêmrâ On the Signs Moses Performed in Egypt” (hereafter, MoS).1 This text has survived (along with several other mêmrê attributed to Ephrem) in a single manuscript of the fifth or sixth century.2 Although J.J. Overbeck produced a printed edition of MoS in 1865,3 Taeke Jansma is the only modern scholar to have discussed it in detail. In an article on the mêmrâ, Jansma strongly contended for accepting it as an authentic work of Ephrem.4 Despite Jansma’s argument, which has been accepted bypb. 320 Brock,5 more recent scholarship has largely overlooked the text.6 This article seeks to correct this omission by providing the first English translation of MoS and integrating this homily more fully into the scholarship on fourth-century Syriac literature. With its origins in the the literary circle or “school” of Ephrem, MoS is a remnant of the early stage of the flourishing of Syriac Christian literary culture. Although its artistic prose style and narrow exegetical format are relatively anomalous, there is reason to believe that MoS bears witness to a poorly-attested genre in early Syriac literature. As such, its style and exegetical method are of great value for enhancing our understanding of this decidedly murky period of Syriac history.

This article makes two major claims about MoS: first, that it dates from the fourth or early fifth century; and second, that it belongs to the “school” of Ephrem. With regard to text’s date, I draw on several streams of evidence: the dating of the manuscript; the lack of influence from the exegesis of Theodore of Mopsuestia and the “Antiochene school” (which rose to prominence in Syriac exegesis in the mid-fifth century); and the absence of monastic interests or priorities in the text (setting it apart from most later Syriac homiletical material). For the second contention of this article—that MoS belongs to the “school” of Ephrem—I offer three major points of evidence. For one, the text is of Syriac origin, employing citations from the Peshiṭta rather than the Septuagint. Further, MoS has some literary relationship (sharing common vocabulary and thematic elements) with Ephrem’s Commentarypb. 321 on Exodus. Finally, although the genre of the text (a prose exegetical homily, also identified as a tûrgāmâ) appears to be relatively unique among extant fourth-century Syriac sources, its exegetical method has only two close parallels in Syriac literature: Ephrem’s Commentary on Genesis and Commentary on Exodus.

Although few scholars have critically examined the Mêmrâ on the Signs, there is a small but important body of scholarship on the text. Following Overbeck’s initial publication of MoS, the earliest evaluation of the text fell to F.C. Burkitt. In an appendix to his study of the Gospel quotations in the writings of Ephrem, Burkitt judged all five prose homilies preserved in B.L. Add. 17189 to be translations from Greek, and therefore inauthentic.7 Later histories of Syriac literature (by Baumstark and Ortiz de Urbina), followed Burkitt in placing the five mêmrê preserved in B.L. Add. 17189 among “Ephremic” works of dubious authorship.8

In a 1961 article, Taeke Jansma challenged this scholarly consensus. His study provided a French translation of MoS and argued in favor of the mêmrâ’s attribution to Ephrem. Jansma’s argument focused primarily upon the close correspondences between MoS and Ephrem’s Commentary on Exodus.9 He identified several common themes in the two texts’ interpretations of Exod 7–8: the contrast between the reality ofpb. 322 Moses’ miracles and the illusory miracles performed by Pharaoh’s magicians10; and the juxtaposition of the magicians’ belief and Pharaoh’s unbelief in the aftermath of the plague of lice (Exod 8:19).11 He then noted close parallels in vocabulary between CommEx and MoS.12 For instance, he observed that after the transformation of Moses’ staff (Exod 7:10), both MoS and CommEx identify it as a ܬܢܝܢܐ (“serpent”), and the trans-formed staffs of Pharaoh’s magicians as ܚܘܘ̈ܬܐ (“snakes”). The Peshiṭta, in contrast, describes both as ܬܢܝ̈ܢܐ.13 As Jansma saw it, the choice of two distinct words for “snake” highlighted the two texts’ common desire to distinguish between the feats of Moses and the magicians. He also observed that both texts use the same words to describe the magicians’ failures to “transform” (root ܫܚܠܦ) the “natures” (ܟܝ̈ܢܐ) of things.14 Once again, such a description fits the two texts’ shared goal of downplaying the achievements of the magicians in favor of the miracles of Moses. Ultimately, Jansma identified no less than fourteen such examples in which the two texts share common vocabulary.15 On the basis of these close correspondences in language and themes between the CommEx and MoS, Jansma concluded that the mêmrâ was the work of Ephrem.

pb. 323Jansma’s analysis advanced our understanding of MoS in two key respects. First, he proved that the text was originally written in Syriac (relying upon Peshiṭta, not LXX, readings from Exodus). Second, he demonstrated the extremely close textual relationship between MoS and Ephrem’s Commentary on Exodus. The most problematic feature of Jansma’s analysis was his singleminded focus on the question of authorship. As I shall demonstrate, the authorship issue is not as clear-cut as Jansma argued. There are several possible interpretations of the literary relationship between MoS and CommEx.

To make the case for an early date of composition (and address the issue of authorship), we must turn to the single surviving manuscript of MoS, the fifth/sixth century codex B.L. Add. 17189.16 The early compilation of the codex indicates that the composition of MoS can date no later than the fifth century. The attribution of authorship in the manuscript is somewhat more complicated. The initial title (on fol. 1v) appears in a later hand, and attributes the homilies to either Ephrem, Basil, or John Chrysostom. Running titles on later folia, however, describe the texts as the work of Ephrem.17 F.C. Burkitt argued that the headings attributing the homilies to Ephrem were written in a different hand and thus offered no evidence as to their attribution at the time the codex was copied.18 Given the diverse character of the collected homilies (some are Syriac compositions and others are translations from Greek) it is possible that when assembling this compilation of homilies, the original scribe did not know or bother to attribute the collection to any single author.19 As it is, the manuscriptpb. 324 itself provides evidence that MoS was composed at a relatively early date, but it does not provide any clear indication of its authorship.

Despite their varied provenance, the five mêmrê of B.L. Add. 17189 share a common profile.20 With the exception of the second homily (On the Fast) they each explicate a single passage of Scripture. This is likely why the scribe identified them in a heading as tûrgāmê (“explanations” or “interpre-tations”).21 Although it is quite difficult to parse the precise nature of such literary terms in early Syriac literature, a similar collection of tûrgāmê by Jacob of Sarug provides evidence that scribes used the word tûrgāmâ to describe a distinct prose homiletic form of early Syriac exegesis.22 Jacob composed the vast majority of his homilies in meter, in the artistic and elevated language of poetry. His six Festal Homilies (tûrgāmê), by contrast, are prose homilies centered upon explaining a passage of Scripture associated with a particular time in the liturgicalpb. 325 year (e.g., the Baptism of Jesus in Hom. 2: On Epiphany).23 These examples of tûrgāmê attest to a particular form of homiletic exegetical composition known to early Syriac writers, characterized by a prose format and a narrow exegetical focus. The manuscript evidence, therefore, supports the following conclusions: that MoS was written in Syriac no later than the fifth century, compiled in a collection of exegetically-oriented homilies—which the scribe identified as mêmrê or tûrgāmê—in the fifth or sixth century, and as a part of that collection was not originally attributed to any particular author. To attribute MoS to the fourth/early fifth century, and to the nebulous literary circle often described as the “school” of Ephrem, will require additional proof.

Although we possess numerous hymns, homilies, and prose works by Ephrem,24 as well as several works by other authors, namely Aphrahat,25 Cyrillona,26 and the anonymous author ofpb. 326 the Book of Steps,27 these extant writings reveal very little about the context of their composition or the lives of their authors. In the attempt to make sense of the shadowy world of fourth-century Syriac Christianity, scholars have sometimes overstated their evidence.28 In fact, we know very little of the social and religious landscape of important cities like Nisibis and Edessa, or of the historical circumstances of the lives of crucial authors like Ephrem.29

pb. 327As a result, contextualizing the extant literature of the fourth century has proven a significant challenge. For exegetical works, one of the most productive avenues thus far has been to trace the connections between Syriac and Jewish exegetical traditions.30 We do not, however, know when and how Syriac and Jewish sources came to share these common traditions. Furthermore, despite efforts to associate fourth-century Syriac exegesis with other contemporaneous Christian traditions—particularly the “Antiochene School”31—the earliest works of Syriac exegesis exhibit marked differences from the work of Diodore and Theodore, as Lucas Van Rompay has shown.32 MoS likewise shows no evidence of thepb. 328 influence of Antiochene exegetical culture, a matter which I will discuss in greater detail below.

The rapid dissemination of Ephrem’s works and the great reputation he quickly attained indicates that his influence inspired a great deal of scribal and literary activity in and beyond the cities where he lived and worked. In his biographical sketch of the life of Ephrem (one of the earliest in any language) the fifth-century Greek historian Sozomen presents a multi-faceted (even contradictory) portrait of the man. Sozomen’s Ephrem is an anchoritic ascetic, a popular hymn-writer, and a renowned teacher and philosopher who produced many famed students.33 Later Syriac sources also described Ephrem as a teacher, associating him with the nebulous “School of the Persians” in Edessa.34 The image of Ephrem as a teacher offers a particularly intriguing context in which to interpret his vast and diverse literary corpus.35 It also provides a possible setting in which to understand the composition of MoS. As much as we might like to envision an exegetical homily like MoS as part of the curriculum of an Ephremic theological “academy,” there is no evidence for a formal Christian “school” in Nisibis or Edessa duringpb. 329 Ephrem’s lifetime.36 We might better conceptualize the teach-ing and writing of Ephrem and his colleagues within the context of an ancient “voluntary association” that only gradually developed the features of a formalized institution, as Adam Becker argues with regard to the “School of the Persians.”37

In a recent article, Jeffrey Wickes proposes a setting for Ephrem’s literary activity that attempts to account for his renown as a teacher and the sophisticated subject matter of his writings. He argues that Ephrem composed the majority of his works within and for an ascetic “literary circle,” a group that would have “blurred” modern distinctions between school, liturgy, and monastery. Wickes writes:

Because of the particularly bookish content of many of the madrāšê, we can think of this small circle neither as the local parish, nor as some kind of proto-monastery,pb. 330 but as a proto-school, gathered to learn and pray. The small gatherings of iḥîdāyê (“single ones”), qaddîšê (“holy ones”), and btûlātâ (“virgins”) read, sang, prayed, discussed, and wrote. The ideals of their life were ascetic, but their asceticism was carried out in especially literary ways.38

Such a literary circle would provide a context in which to comprehend the rapid rise in Ephrem’s fame across the Eastern Roman Empire. Less than twenty years after his death, his reputation had reached Jerome in distant Bethlehem.39 We can envision Ephrem and his disciples engaged not only in prayer and teaching, but also in book production and even potentially translation, working to promulgate and spread their work beyond the confines of Nisibis or Edessa.40 Although we possess no direct evidence of Syriac book production from the fourth century, B.L. Add. 12150, the oldest known Syriac codex (dated to 411 CE), attests to a longstanding history of Syriac scribal practices in Edessa that must underlie the production of a codex of such quality and sophistication.41

Others in Ephrem’s circle seem to have produced their own works during and after his lifetime, some of which are extant. They likely composed the earliest pseudonymous Ephremic writings in the Syriac literary record, as tributes to or continuations of Ephrem’s work.42 This literary circle waspb. 331 probably also the setting in which Ephrem’s followers compiled and revised the apparently heterogeneous Commentary on the Diatessaron.43 Aba is the only other named member of Ephrem’s circle whose works survive today.44 However, until the recent discovery of a previously-unknown treatise On Faith in the library of Deir al-Surian (attributed in marginal notes to Aba), only fragments of his work had been recovered.45 Aba evidently composed several works of exegetical interest, including commentaries on the Diatessaron and the Psalms, and a mêmrâ on Job.46 While they reveal almost nothing of the context of their production, the works of Ephrem and Aba, and some of the earlier Pseudo-Ephremic writings, attest to a highly literate circle, capable of producing works of exegesis, polemic, and theology in poetry and prose.

The central question for our purposes is whether MoS should be attributed to this circle. At first glance, it seems topb. 332 bear little resemblance to other mêmrê associated with Ephrem and his circle, most of which are metrical in form and thematic in content.47 Although its exegesis closely resembles that of Ephrem’s Old Testament commentaries, it is written in an artistic prose akin to that of Ephrem’s Letter to Publius and Mêmrâ on Our Lord.48 Finally, MoS centers on a single biblical account, a method shared by only two mêmrê of likely Ephremic authorship, both of them metrical—the Mêmrâ on Nineveh and Jonah and the Mêmrâ on the Sinful Woman.49 The only possible parallels to MoS from Ephrem and his circle are extant only in fragments: the Mêmrâ on the Prologue of John attributed to Ephrem50 and Aba’s Mêmrâ on Job. Fragments of these mêmrê reveal them to be prose homilies with a narrow exegetical focus, similar, therefore, to MoS. One other comparable text is a short mêmrâ/tûrgāmâ of Syriac origin preserved with MoS in B.L. Add. 17189: On the Coming of the Holy Spirit.51 With its robust Trinitarian formulae and defenses of the divinity of the Holy Spirit, however, the earliest possible date of composition for this text would place it in the decades after Ephrem’s death (around the turn of the fifth century). Furthermore, although the homily focuses on the Pentecost narrative, the author is more willing to make direct theological application and reference other biblical passages than the author of MoS.pb. 333 Despite these differences, it seems to reflect another variation on the same genre. If B.L. Add. 17189 had not survived, there would be no complete extant witnesses to this type of homily from the early period of Syriac literature.

Finally, although MoS bears a close resemblance to Ephrem’s Commentary on Exodus, the exact nature of their literary relationship is unclear. MoS could have been a homiletic reworking of some of the exegetical traditions found in the Commentary on Exodus. It is also possible that MoS was the earlier text, and CommEx was a summary or compilation of existing homiletic exegetical material.52 Nevertheless, the close parallels between the two texts offer the best evidence for attributing MoS to the Ephremic circle. Whatever the case, we cannot be sure of the precise author of MoS. It could, as Jansma argues, be the work of Ephrem. It is just as possible, however, that MoS was written by an unknown member of Ephrem’s circle. In fact, its style and literary form (otherwise unattested in Ephrem’s works) weigh against attributing it to Ephrem himself. Yet other factors, especially its exegetical method, support locating the composition within the Ephremic circle.

MoS offers no outright clues about the context and circumstances of its delivery. Although its artistic prose style and humorous comments on the biblical narrative seem well-suited to the context of a publicly-delivered homily, there is reason to believe that it was not addressed to either a monastic audience or to a public liturgical audience. The exegetical method of MoS gives some indications as to its possiblepb. 334 audience and function. First, although the mêmrâ consistently contrasts the false illusions of the magicians and the works of God through Moses, it strikingly never offers any sort of contemporary moral application of this theme. The reader familiar with Ephrem’s corpus might expect the author to take the opportunity to inveigh against the magicians or astrologers of his own time, associating them with the defeated magicians of Exodus.53 Yet MoS contains no obvious moral or theological exhortations. This approach suggests that the mêmrâ was addressed, not to a public homiletic context, but to a smaller literary circle. Within this circle, it appears to have played a more narrow and constrained role, perhaps correlating to the conventions of this form of exegetical homily, and its distinct (albeit unknown) place in the “curriculum” of the study circle. What, then, might have been the purpose of such a homily?

The exegetical method of MoS most closely resembles Ephrem’s commentaries on Genesis and Exodus. It adheres to a narrow narrative frame of reference and retells the biblical account while clarifying problematic narrative elements. In addition, it gives no symbolic or typological readings of any events in the Exodus narrative. Unlike “literal” exegesis in the Greek tradition,54 it does not dwell on the meaning of the words of the biblical text, but focuses on the interpretation of the narrative.55 In this respect, MoS has almost no parallels in Christian exegetical literature, save Ephrem’s commentaries on Genesis and Exodus. To borrow Lucas Van Rompay’s description of Ephrem’s Old Testament commentaries, “therepb. 335 is a world of difference” between the exegesis of MoS and contemporaneous exegetical works in Greek (as well as later works in Syriac).56 The Armenian commentary on Exodus attributed to Ephrem (almost certainly a translation from a Syriac original) provides a helpful contrast. This commentary frequently cites and alludes to other portions of Scripture, and occasionally embraces allegorical or symbolic readings of the narrative.57 The distinctive quality of the exegesis of MoS (shared only by works of Ephrem) lends further credence to situating the text in the fourth-century literary circle of Ephrem.

While MoS limits itself to the confines of a single biblical narrative and refrains from referencing other biblical passages, its retelling of the text is selective, foregrounding a single theme at the expense of most others: the conflict between the true “signs” performed by Moses and the false “represen-tations” of the magicians. This concern is central to the way that the mêmrâ retells the story of Exodus. It does not engage in detailed exegesis of every verse of the relevant portions of Exodus, but passes over entire sections of the narrative. Sections 1–4 of the mêmrâ depict Moses’ arrival in Egypt, borrowing language from God’s call of Moses in Exod 4:2358 and Moses’ initial encounter with Pharaoh (Exod 5:1–2),59 but completely bypass the account of the bricks without strawpb. 336 (Exod 5:3–23) and the details of Exod 6–7:7. These omissions allow the mêmrâ to proceed dramatically from the initial arrival of Moses to the transformation of the staffs, which it presents as the first battle in the “war” of signs between Moses and Egypt. 60

The mêmrâ’s retelling of Exodus addresses problematic interpretive issues primarily through “narrative expansions,” the addition of events, dialogue, and explanations to the biblical narrative.61 Its dramatic narrative arc and (uneven) use of dialogue place it in an early stage in the development of biblically-oriented dialogue literature in Syriac (types 4 and 5 in Sebastian Brock’s five-part classification of the Syriac dispute and dialogue tradition).62 As a prose text, it stands apart from virtually every known representative of dramatic dialogue literature in Syriac. The fact that MoS does not bear the features of the more developed and formalized Syriac dialogue poemspb. 337 of the fifth- and sixth-century adds further support to dating the text to the fourth century or early fifth century.

Narrative expansions are the homilist’s primary means to develop the central theme of the mêmrâ: the distinction between the actions of Moses and those of the Egyptian magicians.63 MoS consistently presents the mimicry of the various plagues by the sorcerers of Egypt as a “representation” (ܕܘܡܝܐ), an “appearance” (ܐܣܟܡܐ), or a “falsehood” (ܕܓܠܬܐ), rather than “the truth” (ܫܪܪܐ).64 The homilist repeatedly claims that unlike Moses, the magicians only appeared to change the natures of things.65 In fact, as the conclusion explains, their actions were only the result of human “skill” (ܐܘܡܢܘܬܐ), while Moses’ feats were the result of the “creative power” (ܒܪܘܝܘܬܐ) of God.66 The mêmrâ adds a number of supplementary explanations and narrative expansions intended to advance this distinction.pb. 338

For example, after a sarcastic appraisal of the magicians’ efforts to mimic Moses’ production of frogs, the mêmrâ cites details from the narrative of Exodus: “For when Pharaoh petitioned Moses, he prayed and they died. And they piled up their bodies “into heaps,” and the land of Egypt stank from their stench.”67 To this, it adds, “Their carcasses proclaimed the reality of their bodies.” In contrast, then, it describes the fate of the frogs produced by the magicians. Unlike the stinking carcasses of Moses’ frogs, these frogs simply “dissipated into the air like smoke, for their appearance had neither body nor tangible reality.”68 This addition to the Exodus narrative clarifies the distinction between the actions of Moses and the magicians and anticipates the repentance of the magicians following the plague of lice (§10).

The details the mêmrâ adds to the account of the river turning to blood are likewise quite remarkable:

“The magicians also did the same through their enchantments.”69 A misleading representation (ܕܘܡܝܐ ܕܓܠܐ)! Neither true nor accurate (ܫܪܝܪܐ ܚܬܝܬܐ )! Where did they [find] water for themselves to make into blood? For there was not [any] water left in the land of Egypt that had not been turned into blood! The Egyptians longed to drink water, but they were unable. They dug around the river to drink water.70 So from this it is known that the magicians did not make blood from water, for look: there was not any water that one could drink until Moses prayed and the water returned to its first nature!71

In this example, the homilist displays a striking willingness to bend the plain meaning of the text in support of that theme. He argues that, since the magicians possessed no water topb. 339 transform into blood, the plain meaning implied by the text is impossible! He derives this apparent contradiction from a close reading of the biblical narrative, noting (following Exod 7:20–21) that all of the water in Egypt had turned to blood. He then applies this information to the following verse’s claim that “the magicians did the same through their enchantments” (Exod 7:22), and concludes that this would have been impossible.72 This example reveals something of the author’s exegetical process. A problem raised by the biblical account becomes an opportunity to expound an important theological theme: the distinction between divine and creaturely activity. The homilist makes this point in a relatively straightforward exegetical manner, considering a problematic passage by reference to another part of the same passage.

We can characterize the exegesis of MoS as follows: an absence of moral or ascetic exhortation and theological application in favor of a subtle and narrow form of narrative exegesis. In light of this evidence, we may venture the following hypothesis regarding the purpose and performance of the homily. This homily, along with perhaps many others (now lost), was not performed for a liturgical audience, but for a smaller body, probably the ascetic literary circle associated with Ephrem. Within this context, the homily (which may have been variously described as a mêmrâ or tûrgāmâ) likely functioned as a sort of exegetical exercise. It retold a familiar biblical story in a way that clarified potential problems, providing a pattern of interpretation for others to follow. This initial level of exegetical work offered by the homily could then support moral or theological applications of the biblical passage in other contexts.pb. 340

When viewed in relation to other extant fourth-century Syriac literature, MoS is a strikingly unique work. It bears a close literary relationship to Ephrem’s Commentary on Exodus and its exegetical method is nearly identical to that of Ephrem’s commentaries. Its elegant artistic prose, however, resembles texts like Ephrem’s Mêmrâ on our Lord, while its format as a piece of narrative exegesis is reminiscent of Ephrem’s metrical Mêmrâ on Nineveh and Jonah. Simply put, although there are sufficient reasons to date this text to the fourth or early fifth century and to attribute it to the Ephremic literary circle, there is no other piece of extant early Syriac literature quite like this one. Regardless of whether its author was Ephrem himself or someone in his circle (a question which we cannot answer with certainty), MoS provides a crucial piece of evidence for a form of homiletic writing almost entirely absent from the record of early Syriac literature: the prose exegetical mêmrâ or tûrgāmâ. Why such forms of homiletic composition were not favored by later Syriac copyists is unclear. Nevertheless, MoS offers new insight into the little-known formative period of Syriac literary culture in fourth-century northern Mesopotamia, shedding additional light on the exegetical practices and forms of writing common to Ephrem’s literary circle.

PART II: TRANSLATION

Because this is a prose text, I have opted not to present the translation in a lined format, as it appears in Overbeck’s critical edition. Instead, I have created new paragraph-based section numbers. The numbers in parentheses indicate page and line numbers in the critical edition. This format is in line with thepb. 341 precedent set in the most recent English translations of Ephrem’s prose works.73

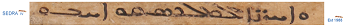

|

§1. Moses, like a divine general, put on hidden armor and came to wage a new war against Pharaoh and his hosts. Without horses and chariots, he fought against armed Egyptians. Without legions and armed troops, he entered to shatter74 walls and smash fortifications. When Egypt was prosperous in its lifestyle, and Pharaoh was exalted in the authority of his kingship, a foreign message of a new war was announced to them. A strange report reached75 their ears, and a word of liberation from the yoke of their slavery was spoken to them. §2. For at that time, [Moses] spoke authoritatively to Pharaoh: “The Lord has sent me76 to you to tell you: ‘Release my firstborn son Israel, whom you have enslaved for yourself [as] a humble slave. Remove your authority from him! He is freeborn! For too long you have subjugated him under [your] authority. He is my own inheritance,77 but you have received him in slaverypb. 342 as if [he is] part of [your] inheritance. Loosen your yoke from his neck! For too long you have worked him harshly. Break your shackles off his neck! For too long you have tormented him78 without compassion. Keep your blade from his children! For too long you have made his mothers bereft [of their children]. Hold back your sword from murder! For too long you have increased his destruction. Let my son79 go and let him serve me. If not, I will kill your firstborn son.”80 This message was heard from Moses. §3. Egypt was in an uproar and its hosts were in turmoil. The magicians and sages assembled before the king, and [people of] all ranks and stations were present for the spectacle. They came to see who this was who had advanced and entered their borders.81 With what was he armed, that he had dared to enter their city? In whom did he place his trust, that he cast this terrifying message into their ears? Who was his escort,82 that he would wish to contend against Egypt and Pharaoh? How great was his power,83 that he scorned them and entered their land? Great and small, strong and weak, assembled, for the message was frightening and it roused the whole court84 with its harsh sound. §4. Now when Egypt had assembled like locusts,85 and Pharaoh was standing among them at their head,pb. 343 Moses and Aaron stood before them and were fearlessly saying to Pharaoh: “The Lord, God of the Hebrews has sent me to you and says, ‘Let my people go and let them serve me.’”86 But Pharaoh, in the hardness of his heart, replied: “I do not know the Lord, and I will not let Israel go.”87 [Moses said]: “O Pharaoh, if you do not know the Lord, you will learn about him.” [Pharaoh asked]: “How will I learn about him?” [Moses said]: “You will learn about him through his power, which I will show you.”88 §5. And Moses threw down his staff, and it became a serpent.89 It gazed at Pharaoh and alarmed him, and at the Egyptians and unsettled them. Then the magicians also threw down their staffs and they became serpents, not truly, but in appearance. To Pharaoh and the Egyptians, they looked to be serpents. But given that they were not [serpents], those staffs were dead and shriveled wood! They did not change from their own natures, and they did not become what they were not. They were unable to flee and could not fight (by their own power, since they had not changed from their first nature. pb. 344But the staff of Moses,90 because it had truly changed and became a serpent in reality, hissed and swallowed up the staffs of the magicians. And by its gorging, it made known the transformation of its nature, and through this affirmed that it had indeed truly become a serpent when it swallowed up the staffs of the magicians. But at this, “the heart of Pharaoh was hardened.”91 Now at this it would have been appropriate for him to recognize that Moses had won the victory, and defeat had befallen the magicians92 from the beginning of the contest (since they arrived with a staff and left without a staff)! But if, as Pharaoh believed, the staffs of the magicians had become serpents (which they did not!), it would have been proper for him to be an honest observer between Moses and the magicians, and to see that the feat of Moses was more powerful than that of the magicians. But “the heart of Pharaoh was hardened,” so that his scourging would increase; and his mind became unbending, so that his end would be evil. He was led astray by the illusions of the magicians so that he would drown in the sea; and he put his trust in an erroneous shadow, so that he would demand those things that he owed the judgment of [divine] justice.93 pb. 345§6. In the morning, [Pharaoh] came out to the river and Moses stood before him and said to him: “If the transformation of the staff did not persuade you, today let the transformation of the river convince you!” And Moses struck the river with [his] staff, and immediately it was transformed into blood (and it was real blood). Immediately the fish in the river that had been turned into blood died,94 because hidden within [the river] was the blood of the children. The fish also died because they had become graves for the Hebrew infants.95 There was blood even “on the wood and on the stones.”96 Indeed, that blood of which Egypt was guilty appeared in every place to accuse those who shed it! “The magicians also did the same through their enchantments”97—a misleading representation! Neither true nor accurate! Where did they [find] water for themselves to make into blood? For there was not [any] water left in the land of Egypt that had not been turned into blood!98 The Egyptians longed to drink water, but they were unable. They dug around the river to drink water.99 So from this it is known that the magicians did not make blood from water, for look: there was not any water that a person could drink until Moses prayed and the water returned to its first nature! And with that, Pharaoh returned100 to his rebellious mind, so that the discipline he deserved because of his wickedness would prevail over him. pb. 346§7. And again the Lord said to Moses, “Speak to Aaron and let him wave the staff over all the water of Egypt, and it will swarm with frogs.”101 The staff was a sign102 to the host contained in the water: like an army it was commanded by the general, and like a battle formation it submitted to the leader. Now, instead of the flocks of birds103 the water had formerly produced, it vomited up terrifying legions.104 And it gave forth an innumerable throng, a single race without variation,105 a new creation born without copulation, multiplied without birth, increased without propagation, grown up without days, and matured without months. A force which is unarmed but not beaten; though without armor, it does not die; without chariots, but overtakes the swift; without skill, but treads down walls; without strategy, but brings down fortifications; without knowledge, but knows how to wage war; contemptible, it humbles kings; weak, it defeats the mighty. [The frogs] buried the land and covered the fields; traversed walls and entered into homes; climbed into the beds of kings and reclined on the couches of rulers; overturned their tables, having defiled their meals;106 and spilled their drinks,107 having climbed into their cups.108 pb. 347§8. “The magicians also did the same through their enchantments”109: another lie, and not the truth! O the blindness of Pharaoh! If the magicians had been useful,110 they would not have imitated Moses’ feat. Rather (had they been able), they would have negated whatever Moses had done. And look: Moses would have failed, those [magicians] would have conquered, and Egypt would have been delivered! For victory in warfare is when one conquers the armies of his enemy, not when one adds to his adversaries. But when the magicians mimic Moses, it neither harms Moses nor helps Egypt, since they do not negate Moses’ feat, but add to his feat! And if the frogs that the magicians had made truly had bodies,111 they would have increased the affliction of Egypt,112 since they were adding to those that Moses had made. But because [the frogs] were113 a deceitful image, [the magicians] were not of any use. However, those that Moses had made were truly frogs, and their death testified [to this]. For when Pharaoh petitioned Moses, he prayed and they died. And they piled up114 their bodies “into heaps,” and the land of Egypt stank from their stench.115 Their carcasses proclaimed the reality of their bodies. But those that the magicians had made dissipated into thepb. 348 air like smoke, for their appearance had neither body nor tangible reality. It is unknown from where they came, nor is it known where they went. Because they did not even exist, they vanished. Again Pharaoh’s heart was hardened. He turned toward himself and continued in disobedience. §9. And the Lord said to Moses: “Speak to Aaron and have him raise [his] staff over the land.”116 So he raised [his] staff and lice appeared in the dust of the earth. [The earth] sprouted, though there was no seed in it. It vomited forth, though it did not produce [a crop]. It sprung up, though it did not receive [seed]: a flying seed, a moving harvest, an inedible eater, an afflicter of all races. The clouds of lice which were swarming and crawling upon each body, descending upon each figure, eating from all flesh, and tormenting [both] animals and humans, were bringing pain to king and poor man alike. No one could care for his companion, for each one was attending to his own pain. There was no slave who helped his master, nor a maidservant who aided her mistress; no father who cared for his son, and no mother who cared for her daughter. They were afflicted before one another, but no one was able to save his companion. The wild beasts were bellowing in pain, and the livestock were crying out in agony. Consumed by their itching, they were knocking down walls. And dust and clouds were rising up from the ground because of their rolling. The wild beasts were scampering off117 in all directions, and the livestock were running amok: herdspb. 349 [of cattle]118 were wandering among the mountains, and flocks [of sheep]119 were splitting off in all quarters. [Both] inside and outside, people were wailing: “O lice, weak army which has defeated the strong! O tiny bodies which have overcome the mighty! O gentle mouths which have filled all mouths with wailing! O wretched sight through which enchantment has been exposed!” §10. Until then, by its shadow, error led astray, but through the crucible of the lice, the fraud of the magicians was exposed. And what they did not wish to confess on the first day, they confessed because of the lice. The lie ran toward the truth, took off its shoes,120 and stayed still. The day grew warm and the clouds dissipated; the sun dawned and darkness fled. Daytime reigned and night was veiled. The magicians were stricken in their bodies and unwillingly confessed the truth.121 They cried out to Pharaoh: “This is the finger of God!”122 But his ears,123 stopped up with contention, did not hear. O hardened heart! He did not believe Moses, nor did he give credence to the magicians. He did not fear God, nor did he wish to let the People go. The magicians turned away from their battle with Moses, like men defeated in a competition. Theypb. 350 ended the contest and gave the crown of victory to that One through whose power Moses had contended. And they did not imitate the actions of Moses any further, for they knew that his skill was not like their own. Rather, it was “the finger of God,” which is stronger than all. Indeed, they saw that it was the creative power of God and not human skill. For through the signs in Egypt was seen the creative power of God, to whom be glory forever! Amen. |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Amar, Joseph P. “Byzantine Ascetic Monachism and Greek Bias in the Vita Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian.” OCP 58 (1992): 123–156.

- _____. The Syriac Vita Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian. CSCO 629–630, Scriptores Syri 242–243. Louvain: Peeters, 2011.

- Amar, Joseph P., and E.G. Mathews, Jr. St. Ephrem the Syrian: Selected Prose Works. Fathers of the Church 91. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1994.

- Baumstark, Anton. Geschichte der syrischen Literatur, mit Ausschluss der christlich-palästinensischen Texte. Bonn: A. Marcus and E. Webers, 1922.

- Beck, Edmund. Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones II. CSCO 311–312, Scriptores Syri 134–135. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1970. .

- Becker, Adam H. Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and Christian Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- Brock, Sebastian P. “Ephrem’s Letter to Publius,” Le Muséon 89 (1976): 261–305. .

- _____. “Jewish Traditions in Syriac Sources.” Journal of Jewish Studies 30, no. 2 (1979): 212–232.

- _____. “Dramatic Dialogue Poems.” In IV Symposium Syriacum 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature. OCA 229. Edited by H.J.W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg and G.J. Reinink. Rome: Pont. Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987.

- _____. “St. Ephrem: A Brief Guide to the Main Editions and Translations.” The Harp 3 (1990): 7–29.

- _____. “Qurillona.” In The Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Edited by Sebastian Brock et al. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2011. .

- Brock, Sebastian P., and Lucas Van Rompay. Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts and Fragments in the Library of Deir al-Surian, Wadi al-Natrun (Egypt). Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 227. Louvain: Peeters, 2014.

- Burkitt, F.C. Saint Ephraim’s Quotations from the Gospel, Texts and Studies: Contributions to Biblical and Patristic Literature 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901.

- Desreumaux, Alain. Trois Homélies syriaques anonymes sur l’Épiphanie. PO 38. Turnhout: Brepols, 1977.

- Drijvers, Han J.W. “The School of Edessa: Greek Learning and Local Culture.” In Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-Modern Europe and the Near East. Edited by Jan Willem Drijvers and Alasdair A. MacDonald. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History 61. Leiden: Brill, 1995.

- El-Khoury, Nabil. “Hermeneutics in the Works of Ephraim the Syrian.” In IV Symposium Syriacum 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature. OCA 229. Edited by H.J.W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg and G.J. Reinink. Rome: Pontifical Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987.

- Féghali, Paul. “Influence des targums sur la pensée exégétique d’Ephrem.” In IV Symposium Syriacum 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature. OCA 229. Edited by H.J.W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg and G.J. Reinink. Rome: Pontifical Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987.

- Forness, Philip Michael. “A Brief Guide to Syriac Homilies,” Version 3. Accessed at .

- Graffin, Francois. Homélies anonymes du VIe siècle. PO 41. Turnhout: Brepols, 1984.

- Griffin, Carl W. “Cyrillona: A Critical Study and Commentary,” Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University of America, 2011.

- _____. The Works of Cyrillona. Picataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2016.

- Griffith, Sidney. “Julian Saba, “Father of the Monks” of Syria,” JECS 2, no. 2 (1994): 185–216.

- _____. “Abraham Qîdunayâ, St. Ephraem the Syrian, and Early Monasticism in the Syriac-speaking World.” In Il Monachesimo tra Eredità e Aperture. Edited by Daniel Hombergen and Maciej Bielawski. Studia Anselmiana 140. Rome: 2004.

- Hansen, Günter Christian. Sozomenos. Historia Ecclesiastica. FC 73. Turnhout: Brepols, 2004.

- Hayes, Andrew. Icons of the Heavenly Merchant: Ephrem and Pseudo-Ephrem in the Madrashe in Praise of Abraham of Qidun. Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies 45. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2016.

- Heal, Kristian. “Reworking the Biblical Text in the Dramatic Dialogue Poems on the Old Testament Patriarch Joseph.” In The Peshiṭta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read at the Third Peshiṭta Symposium, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute 15, edited by Bas ter Haar Romeny. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- Hidal, Sten. Interpretatio Syriaca: die Kommentare des Heiligenpb. 353 Ephräm des Syrers zu Genesis und Exodus mit besondere[r] Berücksichtigung ihrer auslegungsgeschichtlichen Stellung, translated by Christiane Boehncke Sjöberg. Coniectanea biblica. Old Testament series 6. Lund: Gleerup, 1974.

- Jansma, Taeke. “Une homélie anonyme sur la chute d’Adam,” L’Orient Syrien 5 (1960): 159–182.

- ______. “Une homélie anonyme sur la création du monde,” L’Orient Syrien 5 (1960): 385–400.

- ______. “Une homélie sur les plaies d’Egypte,” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 3–24.

- ______. “Une homélie anonyme sur l’effusion du Saint Esprit,” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 157–178.

- ______. “Les homélies du manuscrit Add. 17.189 du British Museum. Une homélie anonyme sur le jeûne,” L'Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 412–440. .

- Kugel, James L. In Potiphar’s House: the Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

- Kmosko, Michael. Liber Graduum. Patrologia Syriaca 1.3. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1926.

- Kronholm, Tryggve. Motifs from Genesis 1–11 in the Genuine Hymns of Ephrem the Syrian, with Particular Reference to the Influence of Jewish Exegetical Traditions. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1978.

- Lange, Christian. The Portrayal of Christ in the Syriac Commentary on the Diatessaron. CSCO 616, Subsidia 118. Louvain: Peeters, 2005.

- Lund, J.A. “Observations on Some Biblical Citations in Ephrem's Commentary on Genesis,” Aramaic Studies 4 (2006): 207–220.

- Mathews, Edward G., Jr. The Armenian Commentaries on Exodus-Deuteronomy attributed to Ephrem the Syrian. CSCO 587–588, Scriptores Armeniaci 25–26. Louvain: Peeters, 2001.

- Melki, Joseph. “Saint Ephrem le syrien, un bilan de l'édition critique,” Parole de l’Orient 11 (1983): 3–88. .

- Millar, Fergus. “Greek and Syriac in Edessa: From Ephrem to Rabbula (CE 363–435).” Semitica et Classica 4, no. 1 (2011): 99–113.

- Nau, François. “Fragments de Mar Aba, Disciple de Saint Ephrem,” Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 17 (1912): 69–73.

- Neuschäfer, Bernhard. Origenes als Philologe. Basel: F. Reinhardt, 1987.

- Ortiz de Urbina, Ignatius. Patrologia Syriaca. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1965. .

- Outtier, Bernard. “Saint Éphrem d’après ses biographies et ses œuvres,” Parole de l’Orient 4, no. 1–2 (1973): 11–33.

- Overbeck, J.J. S. Ephraemi Syri Rabulae Episcopi Edesseni Balaei Aliorumque Opera Selecta. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1865.

- Parisot, Jean. Aphraatis Sapientis Persae Demonstrationes. Patrologia Syriaca 1.1. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1894.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. “Neue Fragmente zum Diatessaron-kommentar des Ephraem-schülers Aba,” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 11 (1980): 117–133.

- Rilliet, Frédéric. Jacques de Saroug: Six homélies festales en prose, PO 43. Turnhout: Brepols, 1986.

- Russell, Paul S. “Nisibis as the Background to the Life of Ephrem the Syrian,” Hugoye 8 (2005): 179–235. .

- Scher, Addai. Cause de la fondation des écoles. PO 4. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1908.

- Sed, Nicolas. “Les hymnes sur le paradis de saint Ephrem et les traditions juives.” Le Muséon 81 (1968): 455–501.

- Segal, J.B. Edessa: The Blessed City. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970. .

- Tonneau, R.-M. Sancti Ephraem Syri in Genesim et in Exodumpb. 355 commentarii. CSCO 152, Scriptores Syri 71. Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1955. .

- Van Rompay, Lucas. “The Christian Syriac Tradition.” In Hebrew Bible, Old Testament: The History of Its Interpretation, Vol. I, Part 1. Edited by Magne Sæbø. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996.

- ______. “Antiochene Biblical Interpretation: Greek and Syriac.” In The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation: A Collection of Essays. Edited by Judith Frishman and Lucas Van Rompay. Louvain: Peeters, 1997.

- ______. “Between the School and the Monk’s Cell: The Syriac Old Testament Commentary Tradition.” In The Peshiṭta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read at the Third Peshiṭta Symposium. Edited by Bas ter Haar Romeny. Monographs of the Peshitta Institute 15. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- Vööbus, Arthur. History of the School of Nisibis. CSCO 266. Subsidia 26. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1965.

- Wickes, Jeffrey T. “Between Liturgy and School: Reassessing the Performative Context of Ephrem’s Madrāšê.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 26, no. 1 (2018): 25–51.

- Wright, William. Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum acquired since the year 1838, Vol. 2. London: British Museum, 1871.

Footnotes

* I would like to express my gratitude to the anonymous readers of this article for their helpful feedback. I am also indebted to Jeffrey Wickes, Susan Ashbrook Harvey, and Philip Michael Forness for reading and commenting on earlier drafts. All errors remain my own.

1 The manuscript heading identifying this mêmrâ as the “first,” could refer to its place as the initial mêmrâ in the codex, or, as Jansma argues, to its place as the first in a series of (now lost) mêmrê on Moses in Egypt. See Taeke Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies d’Egypte,” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 3–24, 23.

2 London, British Library Add. 17189, folios 1v–4v. See William Wright, Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum acquired since the year 1838, Vol. 2 (London: British Museum, 1871), 407. This small codex contains five prose homilies: On the Signs Moses Performed in Egypt (fol. 1r–4v), On the Coming of the Spirit and the Division of the Tongues in the Upper Room (fol. 4v–6r), On the Fast fol. 6r-8v), On the Creation of the World (fol. 9r–12v), and On the Sin of Adam (fol. 12v–15v).

3 J.J. Overbeck, ed., S. Ephraemi Syri Rabulae Episcopi Edesseni Balaei Aliorumque Opera Selecta, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1865), 88–94. Based upon my reading of the manuscript, Overbeck’s edition is a nearly perfect reproduction of the text. In my translation, I offer only a few minor corrections on the basis of the manuscript.

4 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies.”

5 Sebastian P. Brock, “St. Ephrem: A Brief Guide to the Main Editions and Translations,” The Harp 3 (1990): 7–29.

6 See, e.g., the absence of mention of MoS in the exhaustive survey of editions of texts of Ephremic authorship (including works of doubtful and dubious authenticity) in Joseph Melki, “Saint Ephrem le syrien, un bilan de l'édition critique,” Parole de l’Orient 11 (1983): 3–88. MoS also does not appear in the recent guide to Syriac homilies produced by Forness. See Philip Michael Forness, “A Brief Guide to Syriac Homilies,” Version 3, 11–12. Accessed at http://syri.ac/sites/default/files/A_Brief_Guide_to_ Syriac_Homilies_-_Versi.pdf

7 Given that the subject of Burkitt’s inquiry was quotations from the Gospels, and that no such quotations appear in MoS, he did not cite this specific mêmrâ in his analysis of the five homilies. See F.C. Burkitt, Saint Ephraim’s Quotations from the Gospel, Texts and Studies: Contributions to Biblical and Patristic Literature 7 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901), 75–79.

8 See Anton Baumstark, Geschichte der syrischen Literatur, mit Ausschluss der christlich-palästinensischen Texte (Bonn: A. Marcus and E. Webers, 1922), 44; Ignatius Ortiz de Urbina, Patrologia Syriaca (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1965), 68, no. 4.

9 Abbreviated hereafter as CommEx.

10 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 12-15. On the transformation of the staffs into snakes, see MoS §5 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 89–90); CommEx VI (R.-M. Tonneau, ed., Sancti Ephraem Syri in Genesim et in Exodum commentarii, CSCO 152, Syr. 71 [Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1955], 134). On the transformation of the water to blood, see MoS §6 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 90–91); CommEx VII.2 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 135–6). On the plague of frogs, see MoS §8 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 92–93); CommEx VIII.1 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 136–137).

11 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 16. See MoS §10 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 94); CommEx VIII.2 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 137).

12 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 17–18.

13 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 17. See MoS §5 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, p. 89); CommEx VI.1, VII.4 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 134, 136).

14 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 17. See MoS §5 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 90); CommEx VI.1, VII.2 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 134, 136).

15 Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 17-18.

16 Wright, Catalogue, 407.

17 Fol. 2r, 9r, 12v, 13r. For a complete description of these marginal titles, see Wright, Catalogue, 407.

18 Burkitt, Saint Ephraim’s Quotations from the Gospel, 76.

19 On the basis of this (apparently cursory) examination, Burkitt initially judged all of the homilies to be original Greek compositions. (Burkitt, Saint Ephraim’s Quotations from the Gospel, 77). Later, Jansma argued that the fourth and fifth homilies (On the Creation of the World and On the Sin of Adam) were translations of Greek homilies of the Antiochene exegetical tradition. See Taeke Jansma, “Une homélie anonyme sur la création du monde,” L’Orient Syrien 5 (1960): 385–400; idem, “Une homélie anonyme sur la chute d’Adam,” L’Orient Syrien 5 (1960): 159–182. The first three (MoS, On the Fast, and On the Coming of the Holy Spirit) appear to be of Syriac origin.

20 Given the concurring presence of native Syriac homilies as well as translated Greek homilies with an Antiochene exegetical bent within the codex, Jansma attributed this codex to the “School of the Persians” in fifth-century Edessa. (Taeke Jansma, “Les homélies du manuscrit Add. 17.189 du British Museum. Une homélie anonyme sur le jeûne,” L'Orient Syrien 6.1 [1961]: 412–440, 436–37).Jansma overstates the evidence for the existence of such a school (a common problem discussed above). Nevertheless, this collection of Greek and Syriac homilies attests to a transitional moment in Syriac Christian literary production.

21 See B.L. Add. 17189, fol. 12v (page heading).

22 In the case of B.L. Add. 17189, for example, the homilies are variously described as mêmrê and tûrgāmê. For a summary of some of the Syriac terms used for commentary literature, see Lucas Van Rompay, “Between the School and the Monk’s Cell: The Syriac Old Testament Commentary Tradition,” in The Peshiṭta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read at the Third Peshiṭta Symposium, ed. Bas Ter Haar Romeny, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 30.

23 Frédéric Rilliet, ed., Jacques de Saroug: Six homélies festales en prose, PO 43.4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1986). The six homilies are: On Nativity (I), On Epiphany (II), On The Forty-Day Fast (III), On Palm Sunday (IV), On the Friday of the Passion (V), and On the Sunday of the Resurrection (VI). Other early prose homilies I have examined are described in the manuscript tradition as mêmrê or mamllê. This is the case with the anonymous prose homilies edited by Desreumeux and Graffin. See Alain Desreumaux, ed., Trois Homélies syriaques anonymes sur l’Épiphanie, PO 38.4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1977); Francois Graffin, ed., Homélies anonymes du VIe siècle, PO 41.4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1984).

24 For a survey of the editions and translations of Ephrem, see Melki, “Saint Ephrem le syrien.” See also Brock, “St. Ephrem: A Brief Guide.”

25 Jean Parisot, ed., Aphraatis Sapientis Persae Demonstrationes, Patrologia Syriaca 1.1 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1894).

26 Carl W. Griffin, ed. The Works of Cyrillona (Picataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2016). Although scholars have theorized several possible identities, we know nothing of the identity of the poet Cyrillona, the author of five (or six) poems extant in a single manuscript (B.L. Add. 14591). Given that his work seems to originate from around the turn of the fifth century and his style is strikingly similar to Ephrem’s, it is possible that his sophisticated mêmrê and sûgyātâ also emerged from the ascetic literary circle associated with Ephrem. See Sebastian Brock, “Qurillona,” in The Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, edited by Sebastian Brock et al. (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2011), 346–347; Carl W. Griffin, “Cyrillona: A Critical Study and Commentary,” Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University of America, 2011, esp. 1–76.

27 Michael Kmosko, ed., Liber Graduum, Patrologia Syriaca 1.3 (Paris: Firmin-Didot 1926). Scholarly consensus has tended to date this idiosyncratic text to the fourth century. Recently, however, Kyle Smith has raised some valuable challenges to this consensus, arguing that the Book of Steps may be a “purposefully anonymous (and in that sense, pseudepigraphic), fifth-century biblical commentary wherein the author masquerades as a first-century writer”. He offers the ecclesiastical reforms of Rabbula (ca. 430) as a possible moment of tension that may have precipitated the work’s composition. See Kyle Smith, “A Last Disciple of the Apostles: The ‘Editor’s’ Preface, Rabbula’s Rules, and the Date of the Book of Steps,” in Kristian S. Heal and Robert A. Kitchen, eds., Breaking the Mind: New Studies in the Syriac Book of Steps (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2013), 90–91.

28 One of the most striking examples of this is the attempt to place Ephrem’s writings in a chronological sequence, contrasting texts believed to be earlier (from Ephrem’s time in Nisibis) with writings which are allegedly more mature and therefore later (from Ephrem’s time in Edessa). The most detailed implementation of this periodization appears in Christian Lange’s study of the Commentary on the Diatessaron. See Christian Lange, The Portrayal of Christ in the Syriac Commentary on the Diatessaron, CSCO 616, Subsidia 118 (Louvain: Peeters, 2005), 29–33. The problem with this approach is that relies upon subjective assessments of “maturity,” and unproven historical assumptions about the cultural and religious situations in Edessa and Nisibis, respectively.

29 For a thorough summary of the extant evidence and the numerous remaining questions regarding Ephrem’s home city of Nisibis, see Paul S. Russell, “Nisibis as the Background to the Life of Ephrem the Syrian,” Hugoye 8 (2005): 179–235. With respect to the historical details of the life of Ephrem, scholars reject the Syriac Life of Ephrem and Testament of Ephrem as later compositions conveying little accurate data regarding Ephrem’s life. For this problem, see The Syriac Vita Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian, ed. and trans. Joseph P. Amar, CSCO 629/630 (Louvain: Peeters, 2011); idem, “Byzantine Ascetic Monachism and Greek Bias in the Vita Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian,” OCP 58 (1992): 123–156; Bernard Outtier, “Saint Éphrem d’après ses biographies et ses œuvres,” Parole de l’Orient 4:1–2 (1973): 11–33, 12–15.

30 See Sebastian Brock, “Jewish Traditions in Syriac Sources,” JJS 30, no. 2 (1979): 212–232; Paul Féghali, “Influence des targums sur la pensée exégétique d’Ephrem,” in IV Symposium Syriacum 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 229 (Rome: Pontifical Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987), 71–82; Nicolas Sed, “Les hymnes sur le paradis de saint Ephrem et les traditions juives,” Le Muséon 81 (1968): 455–501; Tryggve Kronholm, Motifs from Genesis 1–11 in the Genuine Hymns of Ephrem the Syrian, with Particular Reference to the Influence of Jewish Exegetical Traditions (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1978).

31 See, e.g., Nabil el-Khoury, “Hermeneutics in the Works of Ephrem the Syrian,” in IV Symposium Syriacum, 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 229 (Rome: Pontifical Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987), 95–6; Kronholm, Motifs from Genesis 1-11, 25–7; Sten Hidal, Interpretatio Syriaca: die Kommentare des Heiligen Ephräm des Syrers zu Genesis und Exodus mit besondere[r] Berücksichtigung ihrer auslegungsgeschichtlichen Stellung, trans. Christiane Boehncke Sjöberg, Coniectanea biblica. Old Testament series 6 (Lund: Gleerup, 1974), 25.

32 See Lucas Van Rompay, “Antiochene Biblical Interpretation: Greek and Syriac,” in The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation: A Collection of Essays, ed. Judith Frishman and Lucas Van Rompay (Louvain: Peeters, 1997).

33 See Sozomenos. Historia Ecclesiastica, ed. and trans. by Günter Christian Hansen, FC 73:1-4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), III.16.

34 For the primary source of this tradition, Barḥadbšabbâ’s Cause of the Foundation of the Schools (ca. 600), see Addai Scher, ed., Cause de la fondation des écoles, PO 4.4 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1908) 381. For a thorough commentary on this text, see Becker, Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom, 98–112.

35 Ephrem himself alludes to the activities of teaching on several occasions. For example, in the third Mêmrâ on Reproof, Ephrem develops a lengthy metaphor of the human mind as a tablet upon which to copy and learn God’s law. The image is of a young copyist learning to write in straight lines and duplicate the correct letters. By contrast, he says, humans are inclined to wander off and copy the word “mammon” instead of “God,” when they should be following the example of their divine teacher (Repr. III.389–433). For the best analysis of the limited evidence on Ephrem’s educational background, see Ute Possekel, Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts on the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian, CSCO 102 (Louvain: Peeters, 1999), 48–54.

36 The earliest references to this school originate from the sixth century. Among them are Jacob of Sarug’s Letter 14, Simeon of Beth Arsham’s Letter on Bar Ṣawmâ and the heresy of the Nestorians, and Barhadbšabbhâ’s Ecclesiastical History and Cause of the Foundation of the Schools. For a more in-depth analysis of these sources, see Adam Becker, Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and Christian Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 41–61.

37 Becker, Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom, 69. On the existence of the “School of the Persians,” Becker takes a less credulous view of the sources than his predecessors. J.B. Segal, for example, allows that while “there is no direct evidence that he founded, or taught at, the School of the Persians... it would be strange if he were not associated with it.” (J.B. Segal, Edessa: The Blessed City [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970], 87.). Likewise, Arthur Vööbus sees Ephrem as laying a “foundation” that developed into the school (Arthur Vööbus, History of the School of Nisibis, CSCO 266, Subsidia 26 [Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1965], 8–9). H.J.W. Drijvers even argues for the existence of an earlier “School of Edessa” preceding Ephrem’s time. See Han J.W. Drijvers, “The School of Edessa: Greek Learning and Local Culture,” in Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-Modern Europe and the Near East, ed. Jan Willem Drijvers and Alasdair A. MacDonald, Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History 61 (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 58–59.

38 Jeffrey Wickes, “Between Liturgy and School: Reassessing the Performative Context of Ephrem’s Madrāšê,” JECS 26, no. 1 (2018): 25–51, 45.

39 See Jerome, De Viris Illustribus 115.

40 Sozomen claims that Ephrem’s writings were being copied and translated into Greek even during his own lifetime. See Sozomen, HE III.16.

41 Millar, “Greek and Syriac in Edessa,” 106.

42 Some of Ephrem’s madrāšê cycles (particularly the Madrāšê on Julian Saba and the Madrāšê on Abraham Qidunaya) seem to be of mixed provenance, with an original Ephremic core supplemented by additional pseudo-Ephremic material. The likely explanation for this phenomenon is that Ephrem’s literary and ascetic circle continued to copy, supplement, and disseminate the master’s writings after his death. See Sidney Griffith, “Julian Saba, “Father of the Monks” of Syria,” JECS 2, no. 2 (1994): 185–216, 201; idem, “Abraham Qîdunayâ, St. Ephraem the Syrian, and Early Monasticism in the Syriac-speaking World,” in Il Monachesimo tra Eredità e Aperture, ed. Daniel Hombergen and Maciej Bielawski, Studia Anselmiana 140 (Rome: 2004), 239–64, 250; Andrew Hayes, Icons of the Heavenly Merchant: Ephrem and Pseudo-Ephrem in the Madrashe in Praise of Abraham of Qidun, Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies 45 (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2016), 20.

43 In his study of the Commentary on the Diatessaron, Christian Lange argues that the commentary was of heterogeneous origin, a school text with later additions and corrections by Ephrem’s students. See Lange, The Portrayal of Christ, 66–67.

44 Sozomen names Aba as one of several notable “disciples” of Ephrem, and the title “disciple of Ephrem” frequently accompanies his name in the extant manuscript fragments. See HE III.16.

45 Wadi al-Natrun, Deir al-Surian, Syr. 20C, fol. 76–194v. For a description of this unpublished text, see Sebastian P. Brock and Lucas Van Rompay, Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts and Fragments in the Library of Deir al-Surian, Wadi al-Natrun (Egypt), Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 227 (Louvain: Peeters, 2014), 105–110.

46 For these fragments, which survive in B.L. Add. 17194 and B.L. Add. 14726, see François Nau, “Fragments de Mar Aba, Disciple de Saint Ephrem.” Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 17 (1912): 69–73; Gerrit J. Reinink, “Neue Fragmente zum Diatessaronkommentar des Ephraem-schülers Aba,” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 11 (1980): 117–133.

47 For instance, the three Mêmrê on Reproof and Mêmrê on Nicodemia urge the people of Nisibis to repentance, while the Mêmrê on Faith warn against what Ephrem sees as false teachings.

48 Sebastian Brock first proposed the category of “artistic prose” in his critical edition of the Letter to Publius. See Sebastian P. Brock, “Ephrem’s Letter to Publius,” Le Muséon 89 (1976), 261–305, 263. Like this text, MoS (though not written in meter) employs literary features common to Syriac poetry, such as repetition and personification.

49 Critical editions of both mêmrê can be found in Edmund Beck, ed, Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones II, CSCO 311–312, Scriptores Syri 134–135 (Louvain, 1970).

50 Burkitt reproduces these fragments, with an English translation and commentary, in Burkitt, Saint Ephraim’s Quotations from the Gospel, 59–65.

51 For this text, see Taeke Jansma, “Une homélie anonyme sur l’effusion du Saint Esprit,” L’Orient Syrien 6 (1961): 157–178.

52 In the preface to his Commentary on Genesis, Ephrem describes the Commentary as a brief summary of what he had written about “at length” (ܒܣܓܝܐ̈ܬܐ) in his mêmrê and madrāšê. Perhaps something similar may have been the case with CommEx. See CommGen, Prologue, 1 (Tonneau, Commentarii, 3). This could perhaps explain why the manuscript heading (Vat. sir. 110, fol. 76) identifies CommEx as a tûrgāmâ, a label which—as I have argued—early Syriac scribes used to describe a form of homily.

53 See, e.g., Ephrem’s vehement condemnation of Christian women who turn for help to “magicians” (ܚܪ̈ܫܐ) and “diviners” (ܩܨܘ̈ܡܐ) in the second Mêmrâ on Reproof (Repr. II. 605–614, 759–784).

54 See Lucas Van Rompay, “The Christian Syriac Tradition,” in Hebrew Bible, Old Testament: The History of Its Interpretation, Vol. I, Part 1, ed. Magne Sæbø (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996, 612-641, 624.

55 Lund’s comments on Ephrem’s Commentary on Genesis are also applicable here: “Ephrem's work is primarily a commentary on the story of Genesis, not its text per se.” (Jerome Lund, “Observations on Some Biblical Citations in Ephrem's Commentary on Genesis,” Aramaic Studies 4 [2006]: 207–220, 220).

56 Van Rompay, “Between the School and the Monk’s Cell,” 40.

57 For instance, when commenting on the plague of blood, it pivots to an allegorical reading: “the river with its purity is the people of Israel while Egypt is an example of sin.” To support this reading, the author draws upon Isaiah 1:18 and 1 Cor. 10:1–4. While this is not an uncommon approach in early Christian texts, it is strikingly different from the limited frame of reference of MoS. (Mathews, Armenian Commentaries [ed.], 15; Mathews, Armenian Commentaries [trans.], 14).

58 “Let my son go and let him serve me. If not, I will kill your firstborn son.” (MoS §3; Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 88).

59 “‘The Lord, God of the Hebrews, has sent me to you and says, “Let my people go and let them serve me.” But Pharaoh, in the hardness of his heart, answered [with] the statement: ‘I do not know the Lord, and I will not let Israel go.’” (MoS §4; Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 89).

60 For warfare imagery, see §1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9.

61 For this terminology, see James L. Kugel, In Potiphar’s House: the Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990), 4. For my application of Kugel’s classification to Syriac studies, I am indebted to Kristian Heal, “Reworking the Biblical Text in the Dramatic Dialogue Poems on the Old Testament Patriarch Joseph,” in The Peshiṭta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read at the Third Peshiṭta Symposium, Monographs of the Peshitta Institute 15, ed. B. ter Haar Romeny (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 87–98, 88.

62 Brock proposes a five-type classification system of disputes and dialogues in the Syriac tradition. Type 1 is the classic precedence dispute in alternating stanzas, which appears only in madrāšê (and their sub-genre, sūgyātâ). Type 2 is what Brock calls a “transitional form... where the two parties no longer speak in alternating stanzas, but are allocated uneven blocks of speech.” Both madrāšê and mêmrê of this sort are extant. Type 3 comprises dialogue madrāšê with a narrative framework and no alternating pattern of speech. Types 4 and 5 are represented in narrative mêmrê which make the narrative framework the forefront. (Sebastian P. Brock, “Dramatic Dialogue Poems,” in IV Symposium Syriacum 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature, OCA 229 ed. H.J.W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg and G.J. Reinink [Rome: Pont. Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987], 136-8).

63 Other added details contribute relatively little to the primary themes of the mêmrâ, but do serve to address other potential questions raised by the biblical narrative. For instance, in the mêmrâ’s account of the Nile turning to blood, it explains that the river had changed into blood because it contained the blood of the Hebrew children. Similarly, the fish in the river died (Exod 7:21) “because they had become graves for Hebrew infants.” (MoS §6 [Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 90]). The same explanation also appears in CommEx VII.1.

64 See Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 13–16.

65 Jewish sources also make this distinction. See, for example, Josephus, JA II.14. A similar concern appears in Ephrem’s Commentary on Exodus (see VIII.1) as well as the pseudo-Ephremic Armenian commentary on Exodus: “But [the sorcerers] did not actually or truly change created things as Moses [had done], but they did perform them by illusions to lead astray those who were watching... For if they could not interpret the clear and plain dream of Pharaoh, how could they possibly change created things?” (Mathews, Armenian Commentaries [ed.], 18; Mathews, Armenian Commentaries [trans.],16).

66 MoS §10 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 94). Elsewhere, Ephrem draws clear distinctions between divine ܥܒܘܕܘܬܐ and creaturely ܐܘܡܢܘܬܐ. Although the terminology for divine “creative power” is different here, the concept is the same. See Amar and Mathews, Selected Prose Works, 240, n. 97.

67 Exod 8:14.

68 MoS §8 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 92).

69 Exod 7:22.

70 Exod 7:24.

71 MoS §6 (Overbeck, S. Ephraemi, 91).

72 Jansma makes the odd claim that such inconsistencies between the narratives of MoS and Exodus were meant to capture the attention of the audience. See Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 19.

73 Joseph P. Amar and Edward G. Mathews, Jr., trans., St. Ephrem the Syrian: Selected Prose Works, Fathers of the Church 91 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1994).

74 Syr. ܢܬܪܘܥ. This has a passive sense, but it is immediately followed by the active imperfect verb ܢܟܒܘܫ. For the sake of internal consistency, I have rendered both as active.

75 The sense of the Syriac term ܪܡܐ is more like to ‘cast’ or ‘put’ into the ears. This choice of words suggests something very physical about the act of hearing. However, for the sake of translation, I have opted for more conventional English wording.

76 Except for the first letter, ܫ, the manuscript is illegible. Overbeck reads it as ܫܕܪܢܝ.

77 The Syriac word ܝܪܬܘܬܐ can also be translated as ‘property,’ but the translation ‘inheritance’ is reminiscent of Deut 32:9: “Because the Lord’s portion (ܦܠܓܘܬܗ) is his people, and Jacob his allotted inheritance (ܝܪܬܘܬܗ).”

78 The Syriac verb ܐܥܡܠ can alternatively mean ‘imposed toil.’

79 Jansma rightly identifies manuscript’s addition of a ܘ prefix before ܠܒܪܝ as a scribal error. (Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 4).

80 Exod 4:23.

81 The Syriac is singular.

82 Or ‘his companion’ (ܠܘܝܬܗ).

83 Or perhaps ‘his army’ (ܚܝܠܗ).

84 Syr. ܟܠ ܬܪ̈ܥܝܢ. The noun can have the sense of ‘royal court,’ which is how I translate it here.

85 The Syriac is singular.

86 Exod 5:1.

87 Exod 5:2.

88 A similar line of additional dialogue appears in the Armenian commentary on Exodus attributed to Ephrem: “Although you do not know who God is from [your] sorcerers whom you do know, you will learn about that One whom you do not know.” (Edward G. Mathews, Jr., ed., The Armenian Commentaries on Exodus-Deuteronomy attributed to Ephrem the Syrian, CSCO 587, Scriptores Armeniaci 25 [Louvain: Peeters, 2001], 13).

89 The text uses two different Syriac nouns to describe the serpent of Moses (ܬܢܝܢܐ) and the serpents of the magicians (ܚܘܘ̈ܬܐ), as Jansma points out. (Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 17).

90 As Jansma notes, the text identifies the staff as the staff of Moses, rather than Aaron, as in the text of Exod 7:10–12. (Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 21).

91 Exod 7:13 (almost a direct quotation from the Peshiṭta: ܐܬܥܫܢ ܠܒܗ ܕܦܪܥܘܢ).

92 Following Jansma, I believe that the manuscript’s pointing of ܚܪܫܐ as singular was a copyist’s error. (Jansma, “Une homélie sur les plaies,” 4).

93 The Syriac text here is difficult to understand, but the meaning seems to be that by putting his trust in things other than God, Pharaoh would condemn himself before God’s judgment seat. An alternative (albeit looser) translation might also be possible: “He was so confident in an erroneous shadow so that he would demand those things that were owed to His just judgment.” In this reading, Pharaoh would be described as asking for things that belong rightly to God.

94 Or “immediately the fish in the river died, for they were turned to blood.”

95 Cf. Exod 1:15–22.

96 Exod 7:19. Pesh.: ܒܩ̈ܝܣܐ ܘܒܟܐ̈ܦܐ

97 Exod 7:22.

98 Cf. Exod 7:19.

99 Exod 7:24.

100 The same verb (ܦܢܐ) used to describe the transformation of the blood back into water in the previous sentence.

101 Exod 8:3,5.

102 Syr. ܢܘܦܐ. The same root as the verb ‘wave’ above.

103 Syr. singular

104 The contrast is between flocks of water birds flying off of the river en masse and the hordes of frogs now emerging from the water.

105 The same word (ܫܘܚܠܦܐ) is used elsewhere in this text to describe the true ‘transformation’ wrought by Moses (of the snake and of the river). However, in this case, it seems to have a different sense.

106 Syr. singular

107 Syr. singular

108 All of these verbs in Syriac are singular, presumably referring to the ‘army’ or ‘force’ of frogs. However, for the sake of English translation, I have rendered them as plural.

109 Exod 7:7.

110 Syr. ܚܫܚܘ. The text seems to mean that the magicians were not of any use to Egypt, because they only attempted to add more frogs to those that Moses had already produced. An alternative interpretation is as follows: “If the magicians had been adept [at their sorcery], they would not have imitated Moses” (i.e., they would not have needed to simply mimic whatever he did).

111 Syr. singular.

112 This is another example of the hypothetical perfect.

113 The Syriac reads “it was a deceitful image”, but I have altered this in translation for the sake of clarity.

114 Overbeck has ܟܣܘ, but the manuscript reads ܟܫܘ.

115 Exod 8:14.

116 Exod 8:16.

117 This verb (ܦܘܚ) also carries the sense of ‘to stink,’ so the Syriac description carries a humorous resonance that cannot be conveyed in English.

118 The Syriac uses two similar words: ܪ̈ܡܟܐ ܘܒܩܪ̈ܐ, but I have chosen to render these with a single English word. The distinction between the two words for ‘herd’ is too subtle for English translation.

119 Again, I have simplified more complex Syriac pastoral terminology. The Syriac text uses two nouns: ܓܙܪ̈ܐ ܘܡܪܥܝܬܐ, both of which essentially describe a ‘flock’ of sheep or goats. The distinctions which exist are once again too subtle for English translation.

120 Lit. ‘unshod its feet’ (ܐܢܚܦ ܪ̈ܓܠܝܗ).

121 This somewhat obscure line likely means that being bitten by the lice led the magicians to their eventual (albeit unwilling) confession of God’s power.

122 Exod 8:15.

123 The Syriac is singular.