The Coat of Arms of Moses of Mardin

The core of this paper is an edition of Moses of Mardin’s grant of arms, which, accompanied by relevant excerpts from his unpublished Syriac correspondence, provides new information on the life of this 16th-century Syrian Orthodox monk, who played an important role at the dawn of the European Syriac scholarship. He was not only granted with a coat of arms, but he was also received by Ferdinand I, which shows the importance of his major achievement, the edition of the Syriac New Testament. The paper points out that he lived in the Jesuit college in Vienna with the scions of the most influential noblemen, which illustrates his social milieu. It will be argued that he remained Syrian Orthodox despite his earlier Catholic profession of faith. It will also be argued that Moses acquired the right to bear the described coat of arms without ennoblement, and he probably did not use it.

Introduction

The 16th-century Syrian Orthodox monk, Moses of Mardin, is a key figure in the history of European Syriac scholarship, who did pioneering work in several fields. He took on the lion’s share of the editio princeps of the Syriac New Testament, and he was the teacher of the first generation of Syriac scholars in Europe. As a scribe, he copied a vast amount of manuscripts, and as a diplomatic envoy, he worked on the unity between the Syrian Orthodox and the Roman Catholic Churches.

The two most important corpora of sources on him are the scribal inscriptions and colophons of the manuscripts he copied1 and his Syriac correspondence. Ten letters came down to us from the period 1553–1556. Two of these letters were edited and translated into Latin by Andreas Müller, but the rest are still unpublished.2

Apart from these, Moses’ name pops up sporadically in a great variety of sources. The last two such discoveries challenged earlier conceptions of the beginning of Moses’ career. In 2017, Pier Giorgio Borbone drew attention to a letter written by the Patriarch Ignatius Niꜥamatallah (1557–1576) calling Moses ‘slanderer’ and ‘excommunicated’.3 These words could still be considered as unkind and malignant remarks against someone who might have been his rival in the European market of Oriental scholars. However, another document recently published by Giacomo Cardinali confirms the patriarch’s statements. In a letter sent to Marcello Cervini in 1549, two Syrian Orthodox pilgrims warned the cardinal to be cautious with Moses. They claimed that he had been excommunicated by the patriarch4 and later when he continued his atrocities in Cyprus by forging a letter in the patriarch’s name in order to deceive the Roman Pontiff,5 he was chased away from the Syrian Orthodox community.6 This letter raises many questions,7 but together with Niꜥamatallah’s record, these two independent sources make it worth considering that Moses might have had a bad record in his homeland.8

While these documents undermine Moses’ reputation, a new source bearing witness to his career came up in the National Archives of Austria, where a draft of a charter granting a coat of arms to Moses has been preserved. This paper aims to study and publish this unique document, which – along with relevant information from his unpublished Syriac letters – enriches our knowledge on Moses’ Viennese life with new elements, e.g. on his relationship with King Ferdinand I, on his dwelling place, and his suspected reordination as a Catholic priest.

1. Description of the document

Patents of arms or grant of arms (litterae armales) are elegant diplomas issued on parchment granting the use of a coat of arms to their possessor. The original copy of the diploma was taken by Moses and is likely lost. The document preserved among the Acts of Imperial Ennoblement (Reichsadelsakten–RAA) under the shelfmark 272.57 in the Austrian State Archives is the draft of the diploma. It is written on paper and comprises five folios with the cover. The page in the middle (f. 3) differs from the rest of the document in size and material; it is visibly an addition. The text is full of interlinear and marginal interpolations, many words are blacked out, and almost half of the second page (f. 2v) is crossed out.

Another copy of the text is also preserved in the archives, since, following the chancellery practice, the final version of the grant was copied into a registry (Reichsregisterbuch). This contains only the first part of the document, until the first lines of f. 4r of the draft, concluding: “ac decentibus actibus etc ut in forma communi. Datum Viennae die XV mensis Martii Anno Domini 1556.”9

The number of corrections in the draft version is surprising, especially because the text of the grant followed a standardized template and it could be easily copied out from a formulary.10 It starts by giving the name and the titles of the issuer (intitulatio). This part in our case is only one word: Ferdinand, since the draft omits the enumeration of his titles. Granting coats of arms was a royal privilege in most European states. In the Holy Roman Empire, the emperor delegated the right to the imperial counts palatin (comites palatini), in the Habsburg Monarchy they could be donated by the Archduke of Austria, or later by the princes of Tirol as well.11 Then comes the arenga, which refers to the magnanimity of the king or emperor and his endeavour to reward merits. This particular document makes reference to the right and just act, that the royal majesty rewards in his munificence not only his subjects but also “aliens and foreigners, whose integrity, moral uprightness and proper knowledge of sciences” (f. 2r) make them commendable. The inscription (inscriptio) mentions the recipient of the grant of arms and the narration (narratio) describes his merits. The disposition (dispositio) contains the description of the arms and crest along with a long enumeration of the possibilities of application. The narratio and the description of the arms are the two paragraphs containing personal information, where the scribe could not continue the monotonous copying. It is no wonder that this latter section contains the most corrections in Moses’ document, which will be discussed in detail below. Then comes a threat of punishment (sanctio) for those who would prevent the recipient from the exercise of the right granted to him. The fine was 25 marks of pure gold, which was to be paid equally into the royal treasury and for the offended side. The corroboration (corroboratio) emphasizes that the document was issued with the signature and the seal of the king. The closing protocol (eschatocollum) contains the date and signature, but on this draft understandably only the date is present.

The largest portion of the text follows a pattern, but a few elements are individual to Moses. These will be discussed in the following one by one.

1. Moses and Ferdinand I (narratio)

The coat of arms was granted to Moses by Ferdinand I, who was at that time archduke of Austria as well as king of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia. Former sources bore witness to their relationship from Moses’ point of view. According to the Latin dedication of the Syriac Gospels, for instance, which Moses copied for the editio princeps and offered to the king, he reckoned Ferdinand as a benefactor of Syriac Christians and a strong supporter against Muslims and Nestorians.12 One of the most obvious points of significance of this grant of arms is that it is a formal acknowledgement of Moses’ achievements by the king and witness to their relationship from Ferdinand’s side. The king enumerated Moses’ merits with the following words:

Since you, the aforementioned Syriac priest Moses of Mardin, are thoroughly known to us on account of the excellent talents of your intellect, your piety, your conscientiousness and the sanctity of your life thanks to the trustworthy and distinguished testimony of many people, and we have understood to what a great praise you have cared for the Christian republic by setting to type the New Testament and other very holy books in the Syriac language, and finally what labour and diligence you have invested in this effort, we must not only acknowledge all these things with a generous heart, but also remunerate them with an exceptional decoration and indeed with the favour of our munificence. (f. 2r–2v).

Words of appreciation were specific to the grants of arms, but giving such a long account for the motivation of the issue of the document was extremely rare. Such a personalised wording and the familiar tone applied here were fairly exceptional.13 Departure from the template might suggest a close or special relation between the donator and the grantee. In fact, Moses’ personal acquaintance with the king is attested by another evidence, too.

One of the most exciting events Moses reported to his main correspondent, Andreas Masius,14 was undoubtedly his meeting with king Ferdinand I. He proudly described this episode in a letter with the following words: “I would like you to know, oh, my brother, that I wrote the Gospels on parchment (super carta bergamono). It is a nice script with gold and silver. I offered it to the king. He was delighted and shook hands with me, as it is customary in Germany”. 15 Unfortunately, the protocols of the royal receptions of this period perished in a fire, so we do not know more about this event, but it had to take place sometime between 10–15 August or 9 October and 9 December 1554, because after that Ferdinand set off to Augsburg.16

Moses probably gained admittance to the king thanks to Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter, who was, without doubt, one of those trustworthy and distinguished people from whose testimony Ferdinand heard about Moses. He was chancellor of Lower Austria and an intimate counsellor of the king.17 As one of the few scholars in Europe who had a basic knowledge of Syriac, he was the one who invited Moses to Vienna after an unexpected encounter. Moses enjoyed Widmanstetter’s hospitality for some time and spent altogether two and a half year between 1553 and 1556 in the Habsburg capital.18 He bestowed much of his time on the editio princeps, therefore it is not surprising that his contribution to the printing of the Syriac New Testament had been highlighted as one of his major achievements in the grant of arms. As for the other very holy books in the Syriac language also mentioned in the document, they can be also identified. Moses copied the book of Ezekiel, a Beth Gazo, which is a Syriac liturgical book, and two grammatical treatises of Barhebraeus. Furthermore, he completed a Syriac (Maronite) Missal and composed two Syriac-Arabic dictionaries.19 All these manuscripts enriched Widmanstetter’s private collection. Apparently, Moses’ and Widmanstetter’s cooperation was mutually beneficial, therefore, keeping in mind Widmanstetter’s influence at the chancellery, it is not unrealistic to suppose that he might have been the initiator of granting Moses a coat of arms.

The granting of the coat of arms on 15 March 1556 could have provided an opportunity to another official reception by the king,20 although Moses did not give a report about it in his correspondence. What we do know is that he was asked to complete a mission, as it becomes clear from the letter he sent to Masius after leaving Vienna: “I arrived in Venice with the books the king sent to our patriarch. These are namely the books of the New Testament we completed in Vienna. And know, oh my brother, that the king ordered 1000 books of the New Testament: he took 500 of them for himself and he sent with me 300 to two patriarchs: to our patriarch and to the patriarch of the Maronites.”21 As for the grant of arms, he did not mention it. On the contrary, he complained to Masius saying: “He (scil. the king Ferdinand) gave me 200 books after all this weariness. And he did not give me any dinars, but only 20 thalers. God knows that I am saying the truth in front of Him and you. From Vienna to Venice, I spent the money on books.”22 Masius added a note to this on the margin stating that Moses received 700 florins for two years. It is not known how Masius was so well-informed. However, if this amount was true, Moses would have been an extremely well-paid person in Vienna. Widmanstetter had a yearly salary of 500 florins as chancellor of Lower Austria, and he obtained 200 florins additionally as commission, probably for his work as superintendent of the university.23 Guillaume Postel, who was invited by Widmanstetter to help with the edition of the New Testament with his experience, earned 200 florins a year as a university teacher. With this salary, he was the best-paid professor at the University of Vienna in 1554.24 As for the living expenses, food and lodging were around 50–60 florins per year for a student in the middle of the 16th century.25 At the Jesuit fraternity house, which was likely Moses’ dwelling place during his Viennese years, as it will be shown below, 26 florins was the yearly fee,26 so with 350 florins a year one could be well-off. In the light of these data, the 20 thalers mentioned by Moses is also an unrealistic amount to be his total salary, and it was probably money for the journey he received before departure.

Nevertheless, Moses apparently hoped to receive extra recognition for his work at the end of his sojourn in Vienna and he imagined a more palpable and exchangeable reward than the king’s appreciative words in the grant of arms. His initial enthusiasm towards Ferdinand evaporated and he left Vienna somewhat disappointed, with a bitter taste in the mouth.

2. The patent of arms in the light of the Ottoman wars (narratio)

According to the document, the king decided to present Moses with this grant, “…in order that he can transmit the memory of his right acts, life and diligence confirmed by our testimony and authority to the ones coming after, and (in order) others be inflamed and incited to a good and right way of life by virtue of his example. (f. 2v)” Why did Ferdinand want Moses’ example to be followed? Beyond the fact that referring to the grantee’s exemplariness is a usual locution of the chancellery, this phrase has a concrete meaning in Moses’ case. Actually, not only the issue of this grant of arms but the whole project of the Syriac publishing can be understood in light of the historical background, namely the war against the Turks. The Ottoman threat and the siege of Vienna in 1529 fundamentally determined Ferdinand’s entire reign. Breicha-Vauthier has already pointed out that the edition of the Syriac New Testament could serve political goals27 and Moses himself was aware of this aspect of their work. In a manuscript he copied in Vienna in 1556, he inserted the following note in cryptography: “May God Almighty grant to Ferdinand, King of the Romans, the defeat of the Turks and a happy government of the peoples subject to him.”28

The Ottoman expansion worried not only the country leaders at the European front lines but also Christians of the Near East. Already in 1527, Maronite bishops and the bishops of Syria appealed to Emperor Charles V asking for his help. They requested 50,000 infantrymen, 100 cavalrymen, and a fleet of 400 sailing ships to complement their 50,000 fighters who were ready to engage in battle against the Turks “for His Majesty”. However, their request was left unanswered, or at least no evidence of answer has been found until now.29 Although looking for possible allies in the Near East in order to attack the Ottomans in the rear coincided with the emperor’s interests, he looked for a more powerful partner and sent envoys further in the East, as far as the Safavid Empire in Iran. The Habsburg–Persian alliance started haltingly but generally worked well until 1555, when the Shah Tahmasp and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent closed the Ottoman–Safavid war and signed the Peace of Amasya. Thus, it was to be feared that Ferdinand would find himself in dire straits if Suleiman could focus on the European seat of war.30 His brother, Charles having announced in 1555 his intention to retire, already started to gradually abdicate parts of his empire. Ferdinand was to take his seat on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, so he had to face the loss of their ally.

It was this particular historical situation when he decided to send 300 copies of the Syriac New Testament to the Maronite and the Syrian Orthodox patriarchs and to grant Moses a coat of arms. Although no official instruction assigned to Moses has been found, he might have played a diplomatic role. Charles V and Ferdinand as well relied several times on the service of Eastern Christians in their diplomatic relations with Oriental powers, like Petrus Maronita and Pietro da Negro.31 Offering the books to the patriarchs as a friendly gift served to express that the king and future emperor did not forget them, whereas Moses’ diploma was concrete evidence proving that the king rewards those who help him somehow.

3. Moses’ family (dispositio)

The grant of arms accurately defines who is authorized to use the described coat of arms: “You, aforementioned Moses of Mardin and Your brothers, Barṣawmo, which means son of Lent,32 Simeon, and Joshua, sons of the priest Isaac in the village of Qaluq at the Mount Qoros in the province of Savur,33 your legitimate spouses and the children born from your legitimate marriage and the ones to be born…” (f. 2v).

A German inscription on the first page of the document resumes the content as: “Grant of arms, Vienna, 15 March 1556. Meredineus Moses, Syrian priest and the sons of his brothers Bartholomew and Isaac,” which is erroneous and might be the result of a cursory reading.34

Moses’ family members can be traced very easily because he regularly made mention of them in his writings. In his first known manuscript, which is a Latin Missal written with Syriac letters in 1549, there is a garshuni inscription made by Moses, in which he invokes God for his family: “Remember, Oh Lord, Moses, the sinner and his father, the priest Isaac, and his mother, Helene, and his brother[s], the priest Barṣawmo, Simeon, and Joshua.”35 A similar supplication enumerating his closest relatives can be found also in the editio princeps of the Syriac New Testament, namely in the colophon of the Acts of the Apostles36 and in his Beth Gazo.37

This detailed display of his family makes it possible to identify other members of his family, too. There is a reader’s note in a copy of Bar Bahlūl’s Lexicon preserved in Halle which was made by a certain Ibrāhīm b. Qiss Masꜥūd b. Qiss Barṣawma b. Qiss Isḥāq living in Qaluq in 1606.38 He is without doubt Moses’ great-nephew. He was not only a passionate bookworm but also a prolific scribe.39 Whether he was aware of his right to use his great-uncle’s coat of arms, we might not know, but at least there is one person who fulfilled Ferdinand’s desire and followed Moses’ example, though not in printing but in copying manuscripts.

4. Moses’ coat of arms (dispositio)

The draft of the grant of arms contains two heraldic descriptions, which is quite odd. Having a closer look at them, however, one can see that they are similar, the one being more detailed and elaborated than the other; actually, they represent two different phases of the same coat of arms. Presumably, the scribe showed a sketch to Moses before copying the text of the draft on the vellum, and he must have asked for a few amendments. Thanks to Widmanstetter, Moses had access to the offices of the Viennese administration, so he might have been present at the moment of the composition of his grant of arms.40 The scribe first tried to add the corrections in between the lines, then continued on the margins, finally crossed out the whole description, and rewrote it on another sheet of paper within his reach.41 That is why this middle folio differs from the others, and that is why there is a seeming discrepancy in the foliation. Onto the fair copy of the document, only the final, expanded version had been carried over.

The heraldic achievement is not depicted on either of these documents, and it is not known whether it was displayed on the charter or not. The grant was valid without the coloured heraldic arms, and, since the costs of the painting had to be paid by the beneficiary, the charters sometimes remained without graphic illustration.42 Nevertheless, on the grounds of the description, Moses’ coat of arms could look like Figure 1.

The coat of arms follows the basic rules of tincture. As for the charges, both the trimount and the church are conventional and often-used elements.43 It is an enigma, however, why Moses chose these figures. Would it be an allusion to Widmanstetter’s coat of arms, which portrays an elephant standing on a trimount and a two-towered building also appears in the crest?44 Or are they canting arms representing somehow the bearer’s name and attributes, which were so popular in German civic heraldry?45 If the latter, the trimount offers an obvious interpretation, since Moses’ home region, Turabdin is a hilly region. The two towns, Mardin and Savur, which are associated with him, are situated on the top of a hill. As for the church, it also can be easily explained, since Moses was clerical. The concrete form of the church, however, might raise a question, because this part of the escutcheon is where Moses made the most amendments: he asked to add oblong windows to the towers, two golden crosses on the top of them, an opening door, and three round windows, which are in a triangular form, one beneath the roof and two at the upper part of the door. Such a nuanced description is almost unusual in heraldry, where the stylization of the charges is an important principle46 and makes one think that Moses had a particular church in his head that he described. However, a quest among the churches playing an important role in Moses’ life did not bring evident result. There was no two-towered church in the settlements of Qaluq, Savur, or Mardin, which are mentioned in the grant of arms (f. 2v) and elsewhere as well, as Moses’ hometowns.47 The seat of the Syrian Orthodox patriarch was at that time in a monastery close to Mardin, called Dayr al-Zaꜥfarān. Being the centre of Moses’ church, it was a place of symbolic importance, and Moses undoubtedly visited it,48 but its churches do not fit Moses’ description either.49 If the church was modelled on a Viennese church, the first choice should be the one-time Carmelite Church (Kirche am Hof), because it was the closest to the Moses’ residence, but this church belonged to a mendicant order, which had to avoid building ostentatious edifices and had no towers, only a roof turret.50 Interestingly, Vienna’s iconic church, the St. Stephen’s Cathedral is depicted with two towers on the Albertinischer Plan, which is the oldest map of Vienna (dated 1422). What is more, they have oblong windows, a pointed roof, and huge crosses on the top (see Figure 2). Even three round windows in triangular form can be noticed on the side, so the resemblance is striking. The crux of the matter is that it is a free and stylized depiction of the church. In reality, the building operations were stalled due to lack of money, and the Northern Tower was only 12 meters high at the beginning of the 16th century.51 Did Moses virtually complete the church? It is questionable, and the absence of the barrel vault is another point of difference. Nevertheless, the other oldest and most notable churches in Vienna (Peterskirche, Ruprechtskirche, Maria am Gestade, Michaelskirche, Schottenkloster, Minoritenkirche) do not fit the description, either.52 Beyond the St. Stephen’s Cathedral there is another possible identification, but there are as many reasons for it as against it. After his return to the Near East, Moses lived in the monastery of Mār Ābay, where he copied a manuscript in 1560/1561.53 This monastery is not far from his birthplace, so it is not impossible that he was among its monks before coming to Europe, too. The church was domed and the monastery was surrounded by a wall with two towers, but they were robust structures serving defensive purposes, not proper church towers.54 Thus, the identity of the church remains uncertain.

5. The crest and Moses’ dwelling place (dispositio)

As for the other parts of the armorial achievement, the helmet is an open helmet, the mantling is gules-silver and azure-or, which was popular in that period. In the crest, there is an angel which probably needs further interpretation. It is puzzling why Moses asked for a blond angel with red and green wings, and why the strip, “what the clergymen call stole” should form an X on his chest. These criteria are, again, additions appearing only in the second, more extensive version of the description.

In Byzantine art, angels are sometimes represented in orarion, i.e. eastern stole, which is the distinguishing mark of the deacon in oriental rites. This portrayal had an impact on Western iconography as well and some examples of this representation are attested in the West.55 It appeared even in heraldry, such an angel is depicted in the coat of arms of Engelberg, for instance.56 Moses, however, did not need to go to Engelberg to see angels wearing orarion. He could observe them thoroughly in Vienna when the homily was boring at the Carmelite Church (Kirche am Hof), which was only at two steps from his supposed home.

Arriving in Vienna, Moses was probably hosted by Widmanstetter, as it was already pointed out above, but later he moved to a student home, as it becomes clear from an instruction he gave to Masius: “And if you, beloved Sir, write to me, send the writing to the Alconlegio, since I live now with studiosi.”57 This ‘conlegio’ was most likely the Jesuit college. Juan Alfonso de Polanco noted in his Vita Ignatii that the sons of the chancellor Jakob Jonas and other high-ranking persons lived with the Jesuits in two small separate houses under Jesuit discipline.58 Peter Canisius, one of the most famous Jesuits in Vienna and later provincial wanted to establish a fraternity house for the “wealthiest young noblemen” already in 1553, but the Dominican Monastery, where the Jesuits lived at that time provisionally, was not suitable for this goal.59 Having taken into possession the Carmelite Monastery in April-May 1554, the Jesuits immediately set up the student residence, which opened its gates on 4 July 1554. Initially, six or seven young adolescents, among them the four sons of Jacob Jonas, lived there under the supervision of Johannes Dirsius, but their number increased rapidly, up to 120 in 1574.60

That Widmanstetter was also among the “high-ranking persons” sending their relatives to the Jesuits is not a groundless supposition. He and Jacob Jonas were good friends and they both belonged to the biggest supporters and to the inner circle of the Society of Jesus.61 Widmanstetter maintained especially good relations with the order and he was linked to it with thousand threads: his younger brother studied also at the Jesuits and entered the order in 1556,62 he asked the Jesuits’ help to acquire Japenese and Indian alphabet for the printing press,63 and he was member of the committee set up by Ferdinand I to find a new building for the order.64 His fame reached even the founder, Ignatius of Loyola,65 so he could easily have found a place for Moses. The ultimate reason for this hypothesis is that Moses himself mentioned Canisius in one of his letters. Apparently, the Jesuit superior instructed him how to dress: “Do not write in your letters ‘padre’, because I am in priestly garb here, not in a monastic dress. Formerly, I was in Vienna in laic dress, like in the first year, and after many times Canisius spoke with me and dressed me as a priest.”66

Moses, therefore, lived in the immediate vicinity of the Carmelite Church (Kirche am Hof), the high altar of which was a huge, 10 meters wide polyptych, the masterpiece of an unidentified master called Albrechtsmeister.67 On the external pair of wings, the master depicted 16 invocations of the Virgin Mary representing the angels, mostly with blond hair, red-green wings and in some cases with orarion, just like in Moses’ crest.68 These panels became the characteristic of the church, which is called till today ‘Church to the Nine Choirs of Angels’ (Kirche zu den neun Chören der Engel), so it is not astonishing that they served as a source of inspiration for Moses, too.

As for the other parts of the angel, the book of the Gospels in his hand is an obvious allusion to Moses’ major Viennese accomplishment, the Syriac New Testament. The standard in his right hand contains a motto in abbreviated form: V.S.E.C. The expansion of the abbreviation is provided in the text, it means “One Holy Catholic Church.” The elucidation of this motto is more problematic since it is difficult to guess why Moses chose it.

6. Moses’ motto and his supposed conversion to Catholicism (dispositio)

At first sight, this motto seems to be a commitment to the Catholic Church. As a matter of fact, ‘One’, ‘Holy’ and ‘Catholic’ are the attributes of the Church expressed in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, which is acknowledged by most of the Christian denominations: Oriental Christians as well as Catholics and Protestants equally. Moses’ religious affiliation is a controversial issue, which has not been fully clarified yet. Originally, he was Syrian Orthodox, but many signs indicate that he might have converted to Catholicism. His motto provides an opportunity to take a closer look at this question.

The most concrete evidence for his possible conversion to Catholicism is his Catholic profession of faith he made before the Pope and the cardinals during his second stay in Rome in 1552.69 There are, however, many uncertainties concerning this document and its exact status is unclear.70 There is, for instance, an inconsistency between this act and his behaviour a few months later. In May 1553, Roman cardinals wanted to reordain Moses in a proper, Catholic way, but he firmly resisted. He wrote to Masius in an indignant tone calling the Roman prelates “lacking love and desiring vain glory.”71 Admittedly it was a humiliating proposition from Moses’ point of view, but many other non-Chalcedonians had to undergo this procedure; it was an established custom in the Catholic Church.72 One of Moses’ Roman friends, the Ethiopian Giovanni Battista Negro, alias Yohạnnǝs, was reordained and later became the second black bishop and the first black nuncio in the history of the Roman Church.73 If Moses really wanted to become Catholic, he only would have to allow himself to be reordained and thus his dream would have come true. In sum, despite his visible rapprochement to the Catholic Church, Moses left Rome as a Syrian Orthodox.

In the light of this, it is surprising that he appears to be a Catholic priest in Vienna according to the testimony of different documents. In the first instance, he is referred to as a ‘Syrian Catholic priest’ in the text of the grant of arms (f. 2r). The Syrian Catholic Church did not exist at that time, so the word ‘Syrian’ should refer to his birthplace and ‘Catholic’ to his religion. Moreover, Widmanstetter systematically called Moses a Catholic priest in the edition of Syriac New Testament.74 And finally, the same appellation appears in a Latin note in a manuscript, which was copied by Moses in Vienna in January 1556.75

It is no wonder that reading Moses’ above-cited remark on how Canisius instructed him how to dress, Müller was led to the conclusion that after all he probably accepted the request to be reordained as a Catholic priest in Vienna.76 Unfortunately, the ordination protocols of the diocese of Vienna, which could clinch the matter, are preserved only from 1574, but other circumstances do not confirm Müller’s supposition. There were hardly any seminarians at that time in Vienna. In a 20 years period, only 20 young priests finished their studies, i.e. one per year on average, and the majority of the students at the Faculty of Theology were Jesuits.77 If Jesuits gave the bulk of the seminarians and Moses lived among them, it would be obvious that he was reordained with them. Fortunately, the most important ecclesiastical events are soundly documented in Jesuit sources. While these documents make mention of Erhardus Leodiensis’ ordination in 1554 and that of Martinus Stevordiensis and Johannes Dirsius in 1555, Moses’ name does not appear in any of them.78 Another highly relevant source on this question is Moses’ correspondence. Interestingly Moses, unlike in the case of the failed attempt of the Roman hierarchy, did not report about any change in his ecclesiastical status to Masius during his Viennese period. He was so indignant when the cardinals tried to convince him to accept their proposal that it is hard to believe that he would have passed over a similar issue in silence.

While there is no direct evidence for Moses’ Catholic reordination, there is robust evidence on the contrary. His most current self-designations are religiously neutral; he usually referred to himself as Moses the Oriental, Moses of Mardin, or Moses of Savur,79 but there are some exceptions. The ‘Catholic’ adjective never appears in his signatures, contrary to the Jacobite, i.e. Syrian Orthodox adjective, which does occur in some places. In the Syriac colophon of the New Testament he offered to Ferdinand I, he professed his belonging to the denomination of the Jacobite Syrians.80 According to him, the edition of the Syriac New Testament was carried out “for the Jacobite Syrians.”81 His religious affiliation is even more evident from his letters. Every time the Syrian Orthodox Church came up in his correspondence, he referred to it as his church. Writing about the books Ferdinand sent to the Maronite and the Syrian Orthodox patriarchs, Moses called the latter “our patriarch.”82 Writing about the Beth Gazo, Moses explained to Masius that it contains the prayers of their church.83 At another occasion, instructing Masius in liturgical matters Moses wrote: “I would like you to know, oh my brother, that there is a custom in our church, at the Jacobite Syrians, when we commemorate the saints and ask for their intercession.”84 Further examples could be provided, but these instances aptly illustrate that Moses considered himself as a Syrian Orthodox during his Viennese years.

Assessing this evidence, we can state that in Latin texts, which were intended for the general public, and especially in those cases where others talked about Moses, he appeared to be Catholic, but in Syriac texts, which were practically not accessible for the outside world, and in his private correspondence, Moses confessed his Orthodoxy. The best example for this dichotomy is the Gospel he copied for Ferdinand. In the Latin dedication, he expressed his hope, that the Catholic faith will be reinforced in his home against the Nestorians and the Muslims and that God will gather the Syrians “under the wings of the Roman Church and Empire,” but in the Syriac colophon, he explicitly referred to himself as a Jacobite Syrian.85 Why was this double play necessary?

Answering this question, one must not forget the historical background: the religious struggles of the 16th century. In Vienna, Canisius was the front-line fighter of the Counter-Reformation. As a member of the reform commission at the university, he stood for the dismissal of ‘heretic’ professors, while the others inclined to tolerate them as long as they did not propagate their beliefs at lectures.86 Canisius’ religious zeal can be measured by his reaction to the punishment of a professor at the Faculty of Arts, Nikolaus Polites, who had been incarcerated and banished from the country. In a letter to the Jesuit Superior General, Canisius regretted the punishment’s “leniency”, and he was of the opinion it would encourage the “damned plague among professors and students,” while the university was feeding “monsters and heretics.”87

Moses’ judgment as a Syrian Orthodox was different, but his Church was basically also considered to be heretical. Although Oriental Christians were welcomed in Rome and there was intensive contact with the representatives of most denominations, the negotiations aimed at purging these churches of heterodox tenets and embracing them in the Catholic Church. Similarly, there was at that time an ambivalent attitude to the use and legitimacy of Oriental languages, because on one hand, they could serve missionary purposes and supply new arguments for the theological disputes with Protestants, but on the other, scriptures written in these languages could also contain heretical teachings which could be controlled at the expense of great difficulties. Several interest groups contested with each other at the Roman Curia, and with the shift of power relations, it also could change quickly whether Oriental studies and publishing were supported or prohibited. Pope Paul III (1534–1549) and Cardinal Marcello Cervini, later Pope Marcellus II (1555) patronized the edition of the Ethiopian New Testament in 1548–1549,88 but a few years later, in 1553, the Talmud was burned in Rome by the decree of the Roman Inquisition.89 Although the decree was directed against blasphemous Jewish doctrines, regrettably Syriac scriptures also fell victim to the subsequent raid on Hebrew books.90 In 1571, the Antwerp Polyglot Bible, which was the first Polyglot Bible containing the Syriac text of the New Testament, almost failed to obtain the Papal approbation, because the collaborators were suspected of being kabbalistic or in favour of the Talmud and some of their works were on the Index.91 In light of these events, it is not surprising that Moses preferred not to publicize his Syrian Orthodox identity, in order not to plunge into danger the whole Syriac printing project. In this situation, Moses’ motto seems to be a perfect choice, since it was suitable for giving the semblance of being Catholic and for staying true to the Syrian Orthodox beliefs at the same time. The question arises, how conscious this decision was from Moses’ part: what did he perceive from the contemporary political, ecclesiastical affairs?

The initiative might have come from Widmanstetter, whose interest was to make Moses appear as a Catholic in order not to jeopardize his long-cherished publishing project. Moses’ appellation as a Catholic priest in the edition of the New Testament and also in the text of the grant of arms might be attributed to him. At the same time, he was certainly aware of the truth, since he was able to read Syriac and understood Moses’ sincere colophons. What is more, he knew the Syriac version of the Nicene Creed and he was familiar with the dogmatical differences.92

On the other hand, Moses was also well-informed in political and ecclesiastical questions. He followed the Roman political life with attention and he was fully up to date in this field. After the election of Pope Paul IV (1555–1559), Moses evaluated the situation with the following words: “As for the Pope Theatino, I, myself, am not pleased with him. Even if Giovanni Battista Negro becomes more important or less important, there is no hope for me to return to Rome, only if the cardinal of England or Cardinal Morone becomes the Pope.”93 Moses knew these cardinals personally and he could correctly assess the impact of the election on the Oriental studies and on his future. Apparently, he was smart enough to choose such a clever and cunning motto on his own. His circumspection is also attested by the occasion when he warned Masius not to call him a monk because he is known as a priest in Vienna. At the same time, his motto might also be a reflection of his desire for the unity of his church and the Catholic church mentioned in the Latin dedication of the Syriac New Testament.

7. Did Moses become a nobleman?

Having examined the relevant passages of the grant of arms, there is one more question to clarify, notably the aim and sense of this privilege. In public knowledge, the use of coats of arms and nobility are closely related. No wonder, since it was mainly the noblemen who were granted this royal favour. Nevertheless, from the 13th–14th centuries burghers also managed to obtain such a privilege,94 and later, in the 16th–17th centuries it became attainable even for peasants and lower-ranking servants of the royal court.95 It was an established custom of the sovereigns to elevate someone to the peerage, donating coats of arms at the same time, but in these cases the letters’ patent always explicitly referred to the act of ennoblement. In some exceptional cases, however, patents of arms were officially recognised as patents of nobility.96 Moses’ charter does not contain any reference to the nobility, so he was not raised to the noble rank, which is also confirmed by heraldic elements. In the German heraldic tradition, the form of the helm denoted to the social rank of the coat of arms holder: the so-called close helm (Stechhelm) was the standard helm for burghers, while the open helm (Spangenhelm or Bügelhelm) was reserved for the noblemen.97 In the description of Moses’ heraldic achievement, the close helm (galea clausa) is mentioned, and other nobiliary elements, like the crown of nobility and the supporters, are lacking,98 so it is in accordance with the rest of the document.

Beyond nobility, other privileges could also be donated with a coat of arms, like exemption from personal rates and taxes (exemptio ab oneribus), admission in the service of the emperor (familiaritas), the right to seal with red wax (ius cerae rubeae), etc., but Moses does not seem to have obtained any of these. The only thing Moses was authorised in possession of this charter is the use of the coat of arms described in the document. For the subjects of a European monarchy, such a privilege had far-reaching consequences; it was the symbol of social advancement, the antechamber of nobility.99 But for Moses, it was apparently not easy to assess the importance of this favour.

8. On the use of the coat of arms (dispositio)

The document thoroughly describes the possible use of the coat of arms:

“in exercises, in serious or ludic campaigns, at games of javelin tossing or in contests of infantry and cavalry spearmen, in battles, duels, single contests, in any kind of close combats or fights with ranged weapons, on shields, banners, standards, tents, tombs, seals, memorials, signet rings, buildings, furnishings…” (f. 4r)

It would be interesting to know whether and in which circumstances Moses used his coat of arms. This question is difficult to answer, especially because the number of documents related to Moses is very restricted, but some basic considerations can be offered.

After leaving Vienna, Moses travelled to Venice and embarked to sail for Syria. On his way, he stopped on Cyprus, in Famagusta, where he sold a copy of the Syriac New Testament to a certain Georges de Revelles on 18 October 1556. The purchaser noted on the title page of the book that he bought it from “Moses of Mardin from Mesopotamia, Catholic bishop.”100 It is not known what the reason was for the misunderstanding, whether Moses introduced himself as a Catholic prelate or not,101 but his seal might have played a part in it. We are informed about his seal from one of his letters: “As for what you said that ‘there is a cross on your seal,’ [know] that the cross is not [only] for the metropolitans, but [also] for every baptised people who are baptised in the name of the Holy Trinity.”102 Apparently, Moses felt compelled to give an answer to Masius who had presumably objected the use of the cross in his heraldic bearings, which was the privilege of bishops. The seals are no more visible on the letters, but Andreas Müller still saw them in the 17th century and prepared a sketch of it in his book (see Figure 4). This shows a shield divided into four quarters, the first and fourth a cross crosslet, the second and the third a cock. This latter is the symbol of audacity and combativeness, but in Christian context, it is likely a reference to the story of St. Peter’s denial.103 The cross objected by Masius is the one appearing on the shield or rather behind the shield, which in this form was indeed reserved for bishops.104 Moses acquired this seal in Rome before coming to Vienna,105 and he did not hasten to cut a new one with his new coat of arms, as he apparently continued to use it after leaving the city.

Although Moses was planning to return to Europe with Syriac manuscripts as soon as possible, he stayed in the Near East for two decades and reappeared in Rome only in 1578. He lived there until his death, probably 1592, and left his mark on a number of manuscripts.106 There is a codex in which he copied three texts and at the end of one of them, there is a trace of a seal.107 Unfortunately, the surface is blurred and the original figure is invisible. However, the colophon helps to find out what kind of seal it could be, as it reads: “With God’s help, the letter sent by Patriarch of the Syrians to the king Manuel has been finished. Glory be to God. Amen. It was translated from Syriac into Arabic by the miserable Moses, bishop only by name from the denomination of the Syrians.”108 It was not the only occasion when Moses appeared as a bishop. In most of his signatures during this last period of his life, he used this title.109 Whether he was a consecrated bishop or he ascribed to himself this title illicitly, he probably continued to use his old seal, since it was more suitable to pretend that he was a bishop.

In sum, until now not a single object has been found with Moses’ coat of arms. In all likelihood, he did not cut it onto a seal. The other possibilities of use were not really realistic in Moses’ case, so it might be the case that he never used the coat of arms he was granted by Ferdinand on 15 March 1556.

References

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Liber Sacrosancti Evangelii de Iesv Christo Domino & Deo nostro. Reliqua hoc Codice comprehensa pagina proxima indicabit. Div. Ferdinandi Rom. Imperatoris designati iussu & liberalitate, characteribus & lingua Syra, Iesv Christo vernacula, Diuino ipsius ore cõsecrata, et a Ioh. Euãgelista Hebraica dicta, Scriptorio Prelo diligẽter Expressa. Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter and Moses of Mardin (eds.) 1555. Viennae Austria: Michael Zymmerman = Widmannstetter, Johann Albrecht. Ketābā d-ewangelyōn qaddīšā de-māran w-alāhan Yešuʿ mešihā. Rar. 155. Online access: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00070810/images/

Cod. Syr. 5

Cod. Syr. 6

Biblioteca ApostolicaVaticana

Ms. Vat. ar. 7

Ms. Vat. ar. 22

Ms. Vat. ar. 83

Leiden University Library

Ms. Or. 26.756

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Unknown author, Historia collegii Societatis Iesu Viennensis pars I a. 1552-1638. Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken, Cod. 8367. Online access: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10006117 .

Cod. 15162

Ms. Syr. 1.

Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungsarchiv

‘Wappenbrief, Moses Meredineus, Wien, 15 March 1556.’Adelsakten, Reichsadelsakten, box 272, no. 57.

Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv

Reichskanzlei, Reichsregisterbücher, 7 Reichsregister Ferdinand I. (1548–1558)

Pannonhalmi Főapátság

Maggio, L. S.J. Historia Collegii Societatis Iesu Viennensis ab anno 1550 usque ad annum 1567. Ms. 118.E.5

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Ms. or. fol. 13

Assfalg, J. Verzeichniss der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland. Vol. V. Syrische Handschriften. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1963.

Aumer, J. Verzeichniß der orientalischen Handschriften der K. Hof- und Staatsbibliothek in München: mit Ausschluß der hebraeischen, arabischen und persischen; nebst Anhang zum Verzeichnis der arabischen und persischen Handschriften 1875, Reprinted Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1970.

Barṣawm, I. A. Sriṭoto d-Omid w-Merdo. Makhṭūṭāt Āmid wa-Mārdīn. Omid & Mardin Manuscripts. Ed. Ignaṭiyus Zakkay I, Ma‘arrat Ṣaydnāyā: Dayro d-Mor Afrem Suryoyo, 2008.

Bauer, K. F. Das Bürgerwappen. Das Buch von den Wappen und Eigenmarken der deutschen Bürger und Bauern. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag der Hauserpresse, 1935.

Biewer, L. and E. Henning. Wappen. Handbuch der Heraldik. Köln–Weimar–Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2017.

Borbone, P. G. “From Tur ‛Abdin to Rome: The Syro-Orthodox Presence in Sixteenth-Century Rome.” In Syriac in Its Multi-Cultural Context: First International Syriac Studies Symposium, Mardin Artuklu University, Institute of Living Languages, 20-22 April 2012, Mardin, Eastern Christian Studies 23, eds. H.G.B. Teule, E. Keser-Kayaalp, K. Akalin, N. Doru, M.S. Toprak. Leuven: Peeters, 2017, 277–288.

Borbone, P. G. ““Monsignore Vescovo di Soria”, also Known as Moses of Mardin, Scribe and Book Collector.” Khristianskii Vostok 8 (2017): 79–114.

Braunsberger, O. Beati Petri Canisii, Societatis Iesu, Epistulae et acta. Vol I. Friburgi Brisgoviae: Herder, 1896.

Breicha-Vauthier, A. “Le cadre historique de la publication du manuscript.” In Le livre et le Liban jusqu'a 1900. Exposition, ed. C. Aboussouan. Paris: Unesco–Agecoop, 1982, 125–126.

Cardinali, G. “Ritratto di Marcello Cervini en orientaliste (con precisazioni alle vicende di Petrus Damascenus, Mosè di Mārdīn ed Heliodorus Niger).” Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance 80:1 (2018): 77–98 and 80:2 (2018): 325–343.

Cecini, U. “Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter.” In Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Vol. VII. 1500-1600, eds. D. Thomas and J. Chesworth. Leiden–Boston: Brill, 2015, 235–239.

Csízi I. “Kora újkori nemesi címerek.” In Heraldika. ed. Kollega Tarsoly I. and Kovács E. Budapest: Tarsoly Kiadó, 2018, 155–208.

François, W. “Andreas Masius (1514–1573): Humanist, Exegete and Syriac Scholar.” Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 61:3 (2009): 199–244.

von Frank, K. F. Standeserhebungen und Gnadenakte für das Deutsche Reich und die Österreichischen Erblande bis 1806 sowie kaiserlich österreichische bis 1823 mit einigen Nachträgen zum Alt-Österreichischen Adels-Lexikon 1823-1918. Vol. III., Schloss Senftenegg: Selbstverlag, 1967.

Gall, F. Alma Mater Rudolphina, 1365–1965. Die Wiener Universität und ihre Studenten. Wien: Verlag Austria Press, 1965.

Gall, F. Österreichische Wappenkunde. Handbuch der Wappenwissenschaft. Wien–Köln–Weimar: Böhlau, 1996.

von Gévay, A. Itinerar Kaiser Ferdinanďs I. 1521–1564. Wien: Strauhssel. Witwe Und Sommer, 1843.

Gritzner, E. “Heraldik.” In Grundriß der Geschichtswissenschaft, I/4. ed. A. Meister. Lepzig – Berlin: B.G. Teubner, 1912, 59–97.

Guidi, I. “La prima stampa del Nuovo Testamento in etiopico, fatta in Roma nel 1548-1549.” Archivio della R. Società Romana di Storia Patria 9 (1886): 273–278.

Heim, B. B. Heraldry in the Catholic Church: Its Origin, Customs, and Laws. New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1978.

Heiss, G. “Die Wiener Jesuiten und das Studium der Theologie und der Artes an der Universität und im Kolleg im ersten Jahrzehnt nach ihrer Berufung (1551).” In Die Universität Wien im Konzert europäischer Bildungszentren 14.-16. Jahrhundert, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 56, ed. K. Mühlberger and M. Niederkorn-Bruck. Wien–München: Oldenbourg–Böhlau, 2010, 245–268.

Hyvernat, H. “An Ancient Syriac Lexicographer.” The Catholic University Bulletin 8 (1902): 58–74.

Juel-Jensen, B. “Potken’s Psalter and Tesfa Tsion’s New Testament, Modus baptizandi and Missal.” Bodleian Library Record 15 (1996): 480–496.

Kajatin, C. “Königliche Macht und bürgerlicher Stolz. Wappen- und Adelsbriefe in Zürich.” In Alter Adel - neuer Adel? Zürcher Adel zwischen Spätmittelalter und Früher Neuzeit, ed. P. Niederhäuser. Zürich: Chronos Verlag, 2003, 203–210.

Kennerley, S. “Ethiopian Christians in Rome c.1400-1750.” In Religious Minorities in Early Modern Rome. ed. E. Michelson. Forthcoming.

Kessel, G. “Moses of Mardin (d. 1592).” Manuscript Cultures 9 (2016): 146–151.

Kink, R. Geschichte der kaiserlichen Universität zu Wien. Vol I. Wien: Carl Gerold & Sohn, 1854.

Kiraz, G. A. “Introduction to the Gorgias Reprint.” In The Widmanstadt—Moses of Mardin Editio princeps of the Syriac Gospels of 1555, Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2006, i–vi.

Leroy, J. “Une copie syriaque du Missale Romanum de Paul III et son arrière-plan historique.” Mélanges de l’Université Saint Joseph 46 (1970–1971): 355–382.

Levi della Vida, G. Ricerche sulla formazione del più antico fondo dei manoscritti orientali della biblioteca vaticana. Studi e testi 92. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1939.

Lossen, M. Briefe von Andreas Masius und seinen Freunden 1538 bis 1573. Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Rheinische Geschichtskunde, II. Leipzig: Verlag von Alphons Dürr, 1886.

Lukács, L. Catalogi personarum et officiorum Provinciae Austriae S.I. Vol I. Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu 117. Romae: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1978.

Maier, D. “Überlegungen zum Formular von Wappenbriefen der Reichskanzlei (1338–1500)” Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 126 (2018): 34–52.

Mansi, J. D. Stephani Baluzii Tutelensis Miscellanea novo ordine digesta et non paucis ineditis monumentis opportunisque animadversionibus aucta. Vol. III. Lucae: Apud Vincentium Junctinium, 1762.

Masius, A. De paradiso commentarius; scriptus ante annos prope septingentos à Mose Bar-Cepha Syro; Episcopo in Beth-Raman & Beth-Ceno; ac Curatore rerum sacrarum in Mozal, hoc est Seleucia Parthorum. Antverpiae: Ex Officina Christophori Plantini, 1569.

McCollum, A. “Prolegomena to a New Edition of Eliya of Nisibis's Kitāb al-turjumān fī taʿlīm luġat al-suryān.” JSS 58 (2013): 297–322.

McNamee, M. B. Vested Angels: Eucharistic Allusions in Early Netherlandish Paintings. Leuven: Peeters, 1998.

Mühlberger, K. “Universität und Jesuitenkolleg in Wien: Von der Berufung des Ordens bis zum Bau des Akademischen Kollegs.” In Die Jesuiten in Wien, ed. H. Karner and W. Telesko. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2003, 21–37.

Müller, A. “Epistolae duae Syriacae amoebaeae. Una Mosis Mardeni, Sacerdotis Syri, altera Andreae Masii, JCti et Consil. Olim Cliviaci cum versione et notis.” In: Symbolae syriacae, ed. A. Müller. Berolini, 1673, 1–36.

Müller, A. “Dissertationes duae de rebus itidem Syriacis, et e reliquis Mardeni Epistolis maxime. De Mose Mardeno, una; De Syriacis librorum sacrorum Versionibus… altera. Coloniae Brandeburgicae.” In Symbolae syriacae, ed. A. Müller. Berolini, 1673, 1–46.

Müller, M. Johann Albrecht von Widmanstetter 1506-1557. Sein Leben und Wirken. Bamberg: Verlag der Handels Druckerei, 1907.

Nadal, G. Epistolae P. Hieronymi Nadal, Societatis Jesu ab anno 1546 ad 1577 nunc primum editae et illustratae a patribus ejusdem societatis. Vol. I. Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu. Matriti: Typis Augustini Avrial, 1898.

Neck, R. “Diplomatische Beziehungen zum Vorderen Orient unter Karl V.” Mitteilungen des österreichischen Staatsarchivs 5 (1952): 63–86.

Neubecker, O. and W. Rentzmann, Wappenbilderlexikon. München: Battenberg 1974.

Nyulásziné Straub, É. Magyarország címerkönyve. A heraldika alapjai. Budapest: Ceba, 2001.

Palmer, A. Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur ͑Abdin. University of Cambridge Oriental Publications 39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

von Palombini, B. Bündniswerben abendländischer Mächte um Persien 1453-1600. Freiburger Islamstuditen I. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1968.

Perger, R. and Brauneis, W. Die Mittelalterlichen Kirchen und Klöster Wiens. Wiener Geschichtsbücher 19. Wien–Hamburg: Paul Zsolnay Verlag, 1977.

de Polanco, J. A. Vita Ignatii Loiolae et Rerum Societatis Jesu Historia. IV Vols. Matriti: Augustinus Avrial, 1894–1898.

Pfeifer, G. “Wappenbriefe (unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Tiroler Verhältnisse).” In Quellenurkunde der Habsburgmonarchie (16.-18. Jahrhundert). Ein exemplarisches Handbuch, ed. J. Pauser, M. Scheutz and Th. Winkelbauer. Wien–München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2004, 291–302.

Rabbath, A. Documents inédits pour servir à l’histoire du christianisme en Orient ( xvi ᵉ‒ xix ᵉ siècles). Vol. II. Paris–Leipzig: A. Picard et Fils-Otto Harrassowitz, 1910.

Rekers, B. Benito Arias Montano (1527–1598). Studies of the Warburg Institute 33. London: Warburg Institute, University of London, 1971.

Riedenauer, E. “Kaiserliche Standeserhebungen für reichsstädtische Bürger 1519–1740. Ein statistischer Vorbericht zum Thema “Kaiser und Patriziat”.” In Deutsches Patriziat 1430–1740, ed. H. Rössler. Limburg a.d. Lahn: C. A. Starke Verlag, 1968, 27–98.

Robinson, A. P. The Career of Cardinal Giovanni Morone (1509-1580): Between Council and Inquisition. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

van Roey, A. “Les études syriaques d'Andreas Masius.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 9 (1978): 141–158.

Röhrig, F. Der Albrechtsaltar und sein Meister. Wien: Tusch, 1981.

van Rompay, L. “Mushe of Mardin.” In Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, ed. S. Brock et alii. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2011, 300–301.

Salvadore, M. “African Cosmopolitanism in the Early Modern Mediterranean: The Diasporic Life of Yohannes, the Ethiopian Pilgrim Who Became a Counter-Reformation Bishop.” Journal of African History, 58:1 (2017): 61–83.

Sinclair, T. A. Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey. Vol. III. London: Pindar Press, 1989.

Smelova, N. S. and Lipatov-Chicherin, N. A. “Georgii, arkhiepiskop Damasskii: samozvancheskaia intriga v istorii otnoshenii Maronitskoi Tserkvi i Sviatogo Prestola v seredine XVI v.” Khristianskii Vostok 6 (2013): 244–311.

Socin, A. “Zur Geographie des Ṭūr ʿAbdīn.” Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenlindischen Gesellschaft 34 (1881): 237–269.

Steimel, R. “Der Dreiberg. Zum Rechtssinnbild im Wappen.” Germanien 13 (1941): 58–65.

Stow, K. R. “The Burning of the Talmud in 1553, in the Light of Sixteenth Century Catholic Attitudes Toward the Talmud.” Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance 34:3 (1972): 435–459.

Wesselius, J. W. “The Syriac Correspondance of Andreas Masius : A Preliminary Report.” In V. Symposium Syriacum, 1988: Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven, 29‒31 août 1988, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 236, ed. R. Lavenant. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1990, 21–29.

Wilkinson, R. J. Orientalism, Aramaic and Kabbalah in the Catholic Reformation. The First Printing of the Syriac New Testament. Leiden‒Boston: Brill, 2007.

Wilkinson, R. J. The Kabbalistic Scholars of the Antwerp Polyglot Bible. Leiden‒Boston: Brill, 2007.

Wießner, G. Christliche Kultbauten im Ṭūr ʿAbdīn. Teil I. Kultbauten mit traverserem Schiff und Felsanlagen. Textband. Studien für spätantiken und frühchristlichen Kunst 4. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1982.

Wrba, J. “In der Nähe des Königs. Die Gründung des Jesuitenkollegs in Wien.” In Ignatius von Loyola und die Gesellschaft Jesu 1491‒1556, ed. A. Falkner and P. Imhof. Würzburg: Echter, 1990, 331‒357.

Wright, W. Catalogue of Syriac manuscripts in the British Museum acquired since the year 1838. Vol. I. London: Gilbert and Rivington, 1870.

pb.

Annexe

Below is the edition of the draft copy of Moses of Mardin’s grant of arms (Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Reichsadelsakten, box 272, no. 57.). This version has been chosen, because it is more extent than the fair copy, i.e. contains the entire text of the document and the description of the first sketch of Moses’ coat of arms. As this latter was crossed out by the scribe, it is also crossed out in this edition. Only the main body of the text is published here, other inscriptions are discussed above in the article. Abbreviations are expanded and the articulation of the text is designed to ease the understanding.

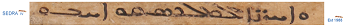

(2r) Ferdinandus etc honorabili, devoto, nobis dilecto Mosi Meredineo Sacerdoti Syro Catholico gratiam nostram regiam et omne bonum. Existimamus Regiam Maiestatem decere non solum subditos suos benemerentes liberalitate et munificentia sua prosequi, verum etiam exteros et alienigenos, quos integritas vitae et morum probitas scientiarumque exacta cognitio commendabiliores efficere solent. Quam rem eo studiosius facimus, quod hinc existimamus Regiam liberalitatem atque beneficientiam latius divulgari, atque in omnes provincias sese extendere, eoque exemplo ceteros admonitos et incitatos ad virtutis sectandae studia reddi propensiores. Quamobrem cum tu praefatus Moses Meredineus Sacerdos Syrus ob egregias animi tui dotes, pietatem, religionem vitaeque sanctimoniam, fidedigno luculentoque multorum testimonio abunde nobis sis cognitus: intellexerimusque quam magna cum laude reipublicae Christianae consulueris in excudendis Novo Testamento aliisque sanctissimis libris Syriaco idiomate, et quantum denique operae et industriae ea in re collocaris, debemus profecto ea omnia non clementi (2v) solum animo agnoscere, sed et peculiari aliquo ornamento atque adeo munificentiae nostrae beneficio remunerare, ut ipse bene actae vitae industriaeque tuae memoriam nostro testimonio auctoritateque comprobatam ad posteros usque transmittere queas, tuoque exemplo alii ad bene recteque vivendum inflammentur incitenturque.

Proinde ex certa nostra scientia animoque bene deliberato et de nostrae regiae potestatis plenitudine tibi praefato Mosi Meredineo et fratribus tuis, Bartomae, idest filio ieiunii, et Simeoni et Ieschua, filiis Isaaci sacerdotis in Caluq villa ad montem Coros provinciae Zaur, legitime coniugati ac filiis vestrum legitimo thoro natis, et deinceps nascituris in perpetuum infrascripta insignia:

clypeum scilicet caeruleum, in quo sint tres montes aurei et super iis ecclesia biturrata argentea cum tecto semicirculari rubeo et tectis duarum turrium itidem rubeis. Scuto ad[?]statur galea clausa, cuius vertice surgat timidius angelus caeruleus praecinctus cum vexillo a dextra candido et litteris V.S.E.C. rubeis significantibus Unam Sanctam Ecclesiam Catholicam. Porro in manu sinistra teneat librum evangelicum apertum. Ex galea utrinque defluant phalerae, quarum alterae sinistrae sint coloris rubei et argentei, alterae vero dextrae caerulei et crocei aureive. Angelus autem sit cinctus stola candida seu fascia candida,

clypeum scilicet caeruleum, e cuius immo exurgant tres colliculi flavi aureive, quorum medius altius paulo quam caeteri attollatur, sustineantque ecclesiam biturritam albam cum tecto semicirculari rubeo, et tectis duarum turrium itidem rubeis et fastigiatis, atque in cruces flavas aureasque desinentibus, quarum utraque turris superne fenestra oblonga illustrari conspicitur, prout et in pariete intermedio porta patens et tres fenestrae orbiculares forma triangulari, sub tecto nimirum una et bine iuxta portae superius limen dispositae apparent. (3r) Scuto imponatur galea clausa equestris phaleris seu laciniis et id genus ornamentis ad laevam albis vel argenteis et rubeis ad dextram croceis seu aureis et coelestinis molliter defluentibus et circumfusis ornata e cuius vertice. Pubetenus emineat imago angeli veste lauzurea fluxa praecinctus, humeros vero fascia (quam stolam Ecclesiastici appellant) candida ita redimitus ut in pectore decussim faciat, alis expansis et rubeo albicante ac viridi coloribus conspicuis, coma flava, et utroque lacerto ad cubitum usque nudato atque extenso, tenens sinistra manu librum evangelicum apertum, dextra vexillum album in cunei modu, formatu hastili flavo aureove et mucronis loco cruce aurea superne ornato, in quo vexillo quatuor litterae rubreae V.S.E.C. Unam Sanctam Ecclesiam Catholicam denotantes descriptae seu depictae cernuntur,

(2v) uti haec omnia pictoris ars et ingenium in medio huiusce nostri diplomatis regii melius representavit, clementer concessimus, donavimus et elargiti sumus, (4r) pro ut harum litterarum nostrarum vigore donamus, concedimus et elargimur, expresse statuentes ac decernentes, quod tu, Moses fratresque tui praedicti, filiique, nepotes, heredes et descendentes legitimi utriusque sexus in omnem posteritatem iam descripta armorum insignia ex hoc tempore deinceps in perpetuum in omnibus et singulis honestis ac decentibus actibus, exercitiis et expeditionibus tam serio, quam ioco, in hastilibus ludis seu hastatorum dimicationibus pedestribus vel equestribus, in bellis, duellis singularibusque certaminibus et quibuscumque pugnis eminus, cominus, in scutis, banneriis, vexillis, tentoriis, sepulchris, sigillis, monumentis, annulis, aedificiis, suppellectilibus, tam in rebus spiritualibus, quam temporalibus et mixtis, in locis omnibus, prout vobis libitum fuerit, aut necessitas vestra postulaverit, habere, gestare et deferre, ac simul quibuslibet privilegiis, immunitatibus, libertatibus et iuribus uti, frui ac gaudere possitis, quibus alii quoque armigeri seu huiuscemodi armorum vel insignium ornamentis decorati utuntur, fruuntur et gaudent iure vel consuetudine. Quapropter omnibus et singulis ecclesiasticis et secularibus, electoribus, principibus, archiepiscopis, episcopis, ducibus, marchionibus, comitibus, baronibus, militibus, nobilibus, clientibus, capitaneis, vicedominis, advocatis, praefectis, procuratoribus, officialibus, quaestoribus, civium magistris, iudicibus, consulibus, regum heraldis et caduceatoribus et denique omnibus nostris et Sacri Romani Imperii ac quorumcumque regnorum, et avitorum nostrorum (4v) dominiorum, et provinciarum nostrarum haereditariarum subditis et fidelibus dilectis cuiuscumque status, gradus, ordinis, conditionis et praeminentiae fuerint, seu quacumque perfulgeant dignitate, firmiter mandamus et praecipimus, ut te praefatum Mosen Meredineum, praedictosque tuos fratres ac liberos, nepotes, heredes et posteros ex vobis legitimo connubio prognatos ac in perpetuum descensuros praescriptis armorum insignibus ac omnibus et singulis honoribus, privilegiis, immunitatibus et iuribus, quibus alii nostri et Sacri Romani Imperii armigeri seu armorum insignibus decorati utuntur, fruuntur, potiuntur et gaudent, libere, pacifice et sine molestia aut impedimento uti, frui, potiri et gaudere sinant, et ab aliis etiam permitti curent.

Quatenus gravissimam indignationem nostram et mulctam XXV. marcharum auri puri fisco nostro regio et parti laesae ex aequo, omni spe veniae sublata, solvendam evitare voluerint, quam poenam his, qui hoc diploma et rescriptum nostrum observare neglexerint aut spreverint, quotiescumque scilicet temere illi adversati fuerint irrogandam decernimus et statuimus.

In cuius rei ampliorem fidem atque testimonium hisce litteris nostris manu nostra propria subscriptis sigillum nostrum regium appendi voluimus.

Datum Viennae, 15 mensibus Martii Anno Domini 1556

pb.

Figures

Figure 1: Moses’ coat of arms. Copyright by Rita Várfalvi.

Figure 2: St. Stephen’s Cathedral, detail of the Albertinischer Plan, 2nd half of the 15th century (the original is dated to 1421/1422), Copyright by Wien Museum.

Figure 3: Mary, Queen of Archangels. Albrechtsmeister: Albrechtsaltar. Copyright by Stift Klosterneuburg.

Figure 4: Moses’ seal. Copyright by Rita Várfalvi.

Footnotes

1 G. Levi della Vida, Ricerche sulla formazione del più antico fondo dei manoscritti orientali della biblioteca vaticana. Studi e testi 92. (Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1939), 206–215, 415–423, 435; J. Leroy, “Une copie syriaque du Missale Romanum de Paul III et son arrière-plan historique” (Mélanges de l’Université Saint Joseph 46 [1970–1971]), 355–382 and P. G. Borbone, ““Monsignore Vescovo di Soria”, also Known as Moses of Mardin, Scribe and Book Collector” (Khristianskii Vostok 8 [2017]), 79–114.

2 A. Müller, “Epistolae duae Syriacae amoebaeae. Una Mosis Mardeni, Sacerdotis Syri, altera Andreae Masii, JCti et Consil. Olim Cliviaci cum versione et notis,” in Symbolae syriacae, ed. A. Müller (Berolini, 1673), 1–36. Jan Wim Wesselius was planning to publish the rest, but later abandoned this project. Cf. J. W. Wesselius, “The Syriac Correspondance of Andreas Masius : A Preliminary Report,” in V. Symposium Syriacum, 1988: Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven, 29‒31 août 1988, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 236, ed. R. Lavenant (Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1990), 21–29. Pier Giorgio Borbone has recently quoted an excerpt from a letter and announced his intention to publish the whole corpus. Cf. Borbone, Monsignore, 84 n. 26, 113–114. The study and the edition of the letters constitute also the basis of my forthcoming PhD.

3 P. G. Borbone, “From Tur ꜥAbdin to Rome: The Syro-Orthodox Presence in Sixteenth-Century Rome,” In Syriac in Its Multi-Cultural Context: First International Syriac Studies Symposium, Mardin Artuklu University, Institute of Living Languages, 20-22 April 2012, Mardin, Eastern Christian Studies 23, eds. H.G.B. Teule, E. Keser-Kayaalp, K. Akalin, N. Doru, M.S. Toprak (Leuven: Peeters, 2017), 277–288, here 285–287.

4 This is an intriguing information, because at that time Niꜥamatallah’s predecessor, Ignatius ꜥAbdallah I (1521–1557) sat on the patriarchal throne, who, according to the current state of research, sent Moses to Rome as his envoy. If this letter proves to be accurate, Moses’ mission will need to be revised.

5 If Moses did so, it would not be unprecedented. Cf. N. S. Smelova and N. A. Lipatov-Chicherin, “Georgii, arkhiepiskop Damasskii: samozvancheskaia intriga v istorii otnoshenii Maronitskoi Tserkvi i Sviatogo Prestola v seredine XVI v” (Khristianskii Vostok 6 [2013]), 244–311.

6 G. Cardinali, “Ritratto di Marcello Cervini en orientaliste (con precisazioni alle vicende di Petrus Damascenus, Mosè di Mārdīn ed Heliodorus Niger)” (Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 80:1 [2018], 77–98 and 80:2 [2018], 325–343), here 340.

7 Why did they send the letter from Paris? Was the letter written in Italian? If they, as pilgrims, were only in transit in Rome, how did they learn Italian? Or else, who helped them in the translation? How did they get in contact with the cardinal?

8 Incidentally, it might happen that Moses himself also referred to his expulsion in one of his manuscripts. In the colophon of the first manuscript he composed in Rome in 1549, he wrote: “Written by the wretched Moses when he took refuge in God in the year 1860 of the Greek Alexander, son of Philip”. London, British Library, Ms. Harley 5512, f. 178r. Leroy tentatively interpreted the expression ‘refuge in God’ (ܡܬܓܘܣ ܒܵܐܬܸܘܵܣ) as ‘pérégrination en Dieu’ (Une copie syriaque, 367.), but in the light of the newest discoveries it can be understood also literally, i.e. ‘he fled for succour to God’, since Moses might have been actually chased away from his home.

9 RK Reichsregister Ferdinand I. 7, 249r–250r. I owe this reference to dr. András Oross, who helped my research in the archives a lot, so I would like to express here my deepest gratitude to him.

10 L. Biewer and E. Henning, Wappen. Handbuch der Heraldik, (Köln–Weimar–Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2017), 45–47; Csízi I., “Kora újkori nemesi címerek” in Heraldika, ed. Kollega Tarsoly I. and Kovács E. (Budapest: Tarsoly Kiadó, 2018), 155–208, here 163–165.

11 G. Pfeifer, “Wappenbriefe (unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Tiroler Verhältnisse)” in Quellenurkunde der Habsburgmonarchie (16.-18. Jahrhundert). Ein exemplarisches Handbuch, ed. J. Pauser, M. Scheutz and Th. Winkelbauer (Wien–München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2004), 291–302, here 294–297).

12 Borbone, Monsignore, 102–103. The manuscript has been preserved in Vienna (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ms. Syr. 1.) and is accessible online: http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/100025DA.

13 Biewer and Henning, Wappen, 45–46; D. Maier, “Überlegungen zum Formular von Wappenbriefen der Reichskanzlei (1338–1500)” (Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 126 [2018]), 34–52, here 39–40, 42.

14 Andreas Masius was a Flemish humanist, who learned Syriac from Moses. He was the addressee of eight letters and the sender of one letter. On his figure see A. van Roey, “Les études syriaques d'Andreas Masius” (Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 9 [1978]), 141–158; R. J. Wilkinson, Orientalism, Aramaic and Kabbalah in the Catholic Reformation. The First Printing of the Syriac New Testament, (Leiden‒Boston: Brill, 2007), 77–94; idem, The Kabbalistic Scholars of the Antwerp Polyglot Bible, (Leiden‒Boston: Brill, 2007), 39–48 and W. François, “Andreas Masius (1514–1573): Humanist, Exegete and Syriac Scholar” (Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 61:3 [2009]), 199–244.

15 Letter sent by Moses to Masius from Vienna, 26 March 1555: Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. or. fol. 13, f. 16r. ܕܥ ܐܘ̄ ܐܚܝ ܕܐܢܿܐ ܟܬܒܿܬ ܠܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ܥܠ ܘܪ̈ܩܐ ܕܡܸܫܟܐ super carta bergamono ܟܬܝܒܬܐ ܫܦܝܪܬܐ. ܥܡ ܕܗܒܐ ܘܣܹܐܡܐ. ܘܩܪܒܬܗ ܠܡܠܟܐ. ܘܚܕܹܝ ܒܗ ܣܰܓܝܼ ܘܝܗܒ ܠܝ ܐܝܕܗ ܐܝܟ ܥܝܳܕܐ ܕܓܰܪܡܲܐܢܝܲܐ܀

16 A. von Gévay, Itinerar Kaiser Ferdinanďs I. 1521–1564, (Wien: Strauhssel. Witwe Und Sommer, 1843).

17 On him see M. Müller, Johann Albrecht von Widmanstetter 1506-1557. Sein Leben und Wirken, (Bamberg: Verlag der Handels Druckerei, 1907); Wilkinson, Orientalism, 137–169 and U. Cecini, “Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter” in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Vol. VII. 1500-1600, eds. D. Thomas and J. Chesworth, (Leiden–Boston: Brill, 2015), 235–239.

18 Letter sent by Moses to Giovanni Rignalmo from Vienna, 23 November 1553: Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. or. fol. 13, f. 21r ܘܗܐ ܣܓܝ ܚܘܒܐ ܡܚܲܘܐ ܠܝܼ. ܗܘ ܘܐܢܬܬܗ “What a great love he and his wife showed towards me.”

19 Borbone, Monsignore, 101–106.

20 Ferdinand was in Vienna in these days. Cf. Gévay, Itinerar.

21 Letter sent by Moses to Masius from Venice, 1 August 1556: Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. or. fol. 13, f. 11r ܐܬܝܬ ܠܐܒܼܷܢܸܬܣܝܲܐ ܥܡ ܟܬ̈ܒܐ ܕܫܕܪ ܡܲܠܟܐ ܠܦܛܪܝܪܟܐ ܕܝܠܢ. ܗܿܢܘܕܝܢ.ܟܬ̈ܒܐ ܕܚܿܕܬܐ ܕܚܬܼܡܢܢ ܒܿܰܒܼܝܷܐܢܢܲܐ. ܕܰܥ ܐܵܘ̄ ܐܳܚܝ ܕܥܒܼܕ ܡܲܠܟܐ ܐܰܠܦܵܐ ܟܬܵܒܵܐ ܕܚܿܕܬܐ. ܚܲܡܸܫܡܵܐܐ ܡܸܢܗܘܿܢ ܐܷܚܼܕ ܐܢܘܢ ܡܲܠܟܐ. ܘܲܬܠܵܬܡܵܐܐ ܫܕܪ ܠܬܪܝܢ ܦܛܪ̈ܝܪܟܸܐ ܥܲܡܝ. ܠܦܛܪܝܪܟܐ ܕܝܠܢ. ܘܕܡܰܪܽܘ̈ܢܵܝܸܐ..

22 Letter sent by Moses to Masius from Venice, 1 August 1556: Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. or. fol. 13, f. 11r ܘܝܲܗܒ ܠܝ ܬܪܝܢ ܡܵܐܐ ܟܬ̈ܒܐ ܡܢ ܒܿܬܪ ܠܸܐܘܬܐ ܣܲܰܓܝܼܺ ܘܕܝܢܪ̈ܐ ܠܐ ܝܲܗܒ ܠܝ ܠܒܲܪ ܡܢ ܥܣܪܝܢ ܛܰܐܠܪ. ܐܠܗܐ ܝܿܕܥ ܕܫܪܪܐ ܐܡܿܪ ܐܢܐ ܩܕܵܡܘܗܝ ܘܩܕܡܝܟ. ܘܐܢܿܐ ܢܸܦܩܸܿܬ ܢܦܩ̈ܬܐ ܥܠ ܟܬ̈ܒܐ ܡܢ ܒܼܝܸܐܢܢܲܐ ܘܥܕܲܡܵܐ ܠܐܰܒܼܷܢܸܬܣܝܲܐ..

23 Müller, Johann Albrecht von Widmanstetter, 102.

24 R. Kink, Geschichte der kaiserlichen Universität zu Wien. Vol I/2, (Wien: Carl Gerold & Sohn, 1854), 164–165.

25 F. Gall, Alma Mater Rudolphina, 1365–1965. Die Wiener Universität und ihre Studenten, (Wien: Verlag Austria Press, 1965), 117.

26 J. A. de Polanco, Vita Ignatii Loiolae et Rerum Societatis Jesu Historia, IV Vols (Matriti: Augustinus Avrial, 1896), Vol. IV, 250.

27 A. Breicha-Vauthier, “Le cadre historique de la publication du manuscript” in Le livre et le Liban jusqu'a 1900. Exposition, ed. C. Aboussouan, (Paris: Unesco–Agecoop, 1982), 125–126.

28 G. Kessel, “Moses of Mardin (d. 1592)” (Manuscript Cultures 9 [2016]), 146–151; Borbone, Monsignore, 105–106. Borbone described another mirror pair (taw’amān) and explored how Moses learned this special technique. Cf. Borbone, Monsignore, 92–95. Apparently, the use of this encrypting method is a characteristic of Moses’ early manuscripts, because there is a mirror pair in his very first manuscript as well (London, British Library, Ms. Harley 5512). On f. 176v-177r one can read: ”ܒܫܡ ܐܒܐ ܘܒܪܐ ܘܪܘܚܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܚܕ ܐܠܗܐ ܫܪܝܪܐ. In Nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus San(c)ti Amen Papa Pavlos III.” Neither Wright in his catalogue, nor Leroy in his study referred to the presence of this taw’amān in the manuscript, that is why it could remain disregarded so long. Cf. W. Wright, Catalogue of Syriac manuscripts in the British Museum acquired since the year 1838. Vol. I. (London: Gilbert and Rivington, 1870), 214–216; Leroy, Une copie syriaque.

29 A. Rabbath, Documents inédits pour servir à l’histoire du christianisme en Orient ( xvi ᵉ‒ xix ᵉ siècles). Vol. II, (Paris–Leipzig: A. Picard et Fils-Otto Harrassowitz, 1910), 616–623; R. Neck, “Diplomatische Beziehungen zum Vorderen Orient unter Karl V” (Mitteilungen des österreichischen Staatsarchivs 5 [1952]), 63–86, here 69 and 82–85.

30 Neck, Diplomatische Beziehungen, 75; B. von Palombini, Bündniswerben abendländischer Mächte um Persien 1453-1600, Freiburger Islamstuditen I (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1968), 84.

31 Palombini, Bündniswerben, 65–85.

32 The document calls Moses’ eldest brother Bartoma, which is incorrect. Presumably, the scribe did not know the name Barṣawmo, that is why Moses had to explain, that it means son of Lent in Syriac. Apparently, the scribe tried to write down the name by hearing and he chose a similar sounding name.

33 On the topography of this region see A. Socin, “Zur Geographie des Ṭūr ʿAbdīn” (Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenlindischen Gesellschaft 34 [1881]), 237–269, here 265; A. Palmer, Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur ͑Abdin, University of Cambridge Oriental Publications 39 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), XIX–XXII, 21–22.

34 „Wappenbrief. Wien, 15. März 1556. Meredineus Moses, syrischer Priester dann die Söhne seiner Brüder Bartholomäus und Isaak” (2r). Karl Friedrich von Frank relayed this information without verification. Cf. K. F. von Frank, Standeserhebungen und Gnadenakte für das Deutsche Reich und die Österreichischen Erblande bis 1806 sowie kaiserlich österreichische bis 1823 mit einigen Nachträgen zum Alt-Österreichischen Adels-Lexikon 1823-1918. Vol. III, (Schloss Senftenegg: Selbstverlag, 1967), 228.

35 ܐܬܼܟܪ ܐܘ̄ ܡܪܝܐ ܠܡܘܣܝ ܐܠܟܐܛܝ ܘܠܐܒܘܗ ܩܣܝܣ ܐܝܣܚܩ ܘܐܡܗ ܗܝܠܐܢ. ܘܐܟܘܗ ܩܣܝܣ ܒܪܨܘܡܐ ܘܫܡܥܘܢ ܘܝܫܘܥ. London, British Library, Ms. Harley 5512, f. 166v.

36 Liber Sacrosancti Evangelii, Acts of the Apostles, f. 38r: ܨܰܠܲܘ ܥܰܠܼ ܡܘܽܫܸܐ ܡܚܻܝܠܐ ܒܰܪ ܩܲܫܝܫܐ ܐܝܣܚܵܩ ܡܕܢܚܵܝܵܐ ܘܥܰܠ ܐܡܗ ܗܷܠܷܐܢܻܝ. ܘܥܰܠ ܐܚܘ̈ܗܝ ܩܲܫܝܫܐ ܒܲܪܨܰܘܡܳܐ ܘܫܸܡܥܘܢ ܘܝܫܘܽܥ ܘܟܠ ܚܰܕ ܐܝܟ ܨܠܘܽܬܗ ܢܸܬܦܪܰܥ ܐܡܝܢ݂ Cf. A. Müller, “Dissertationes duae de rebus itidem Syriacis, et e reliquis Mardeni Epistolis maxime. De Mose Mardeno, una; De Syriacis librorum sacrorum Versionibus… altera. Coloniae Brandeburgicae” in Symbolae syriacae, ed. A. Müller (Berolini, 1673), 1–46, here 5.

37 Borbone, Monsignore, 106; Kessel, Moses of Mardin, 149.

38 J. Assfalg, Verzeichniss der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland. Vol. V. Syrische Handschriften, (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1963), 115.