The Primordial Language in Ephrem the Syrian

This article contributes to the discussion on the primordial language in the late antique Syriac tradition, specifically in the legacy of Ephrem the Syrian (c.306–373). The important milestone is the Cave of Treasures, a pseudepigraphal historical narrative ascribed to Ephrem but dated to the mid-sixth or early seventh century. The text emphatically asserts the priority of Syriac over Hebrew. The idea would later become popular among both Eastern and Western Syriac intellectuals. Some scholars have taken it as a testimony of Ephrem’s views or an indication that these ideas had been in circulation in his time. However, the authentic writings of Ephrem the Syrian are surprisingly equivocal concerning the pre-Babel language. We can partially reconstruct his views by collating the bits of information from indirect statements in his hymns and his Commentary on Genesis. Analyzing Ephrem’s discussion on the tower of Babel and language confusion helps rectify the assumption that Ephrem championed Syriac primordiality.

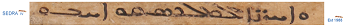

The Cave of Treasures, a historical narrative dated to the mid-sixth or the early seventh century, declared that Syriac was humanity’s primordial language before Babel’s confusion of tongues that started the process of linguistic diversification. Its author emphatically stated that those who disagreed with such a view were wrong: “From Adam until this time [Babel], they [people] were all of one speech and one language. They all spoke this language, this is to say, Syriac, which is Aramaic, and this language is the king of all languages. Now ancient writers have erred in that they said that Hebrew was the first, and in this matter they have mingled an ignorant mistake with their writing.” The narrator concludes that “all the languages there are in the world are derived from Syriac, and all the languages in books are mingled with it.”1

This study contributes to the discussion about the primordial language in the early Syriac tradition and specifically in Ephrem the Syrian (c.306–373). The Cave of Treasures is an important milestone. The dating of the text is tentative and much contested. However, the arguments in favor of the mid-sixth- to early-seventh-century date seem most convincing.2 This goes with an acknowledgment that this multilayered composition incorporated many earlier sources. It absorbed influences from different cultural and religious contexts, while the biblical narrative provided the principal historical frame.3 The text unequivocally asserts the priority of Syriac over Hebrew, and this idea would later become popular among both Eastern and Western Syriac intellectuals.4

Since the author of the Cave of Treasures ascribed it to Ephrem the Syrian in what seems to be a deliberate pseudepigraphic strategy – i.e., using Ephrem’s name was “an essential element of its actual author’s literary and ideological agenda”5 – this attribution is attested in the majority of Syriac manuscripts and has generated a robust tradition. Therefore, some scholars have taken the discussion of Syriac primordiality in this composition as a testimony of Ephrem’s views or as an indication that these ideas circulated in the Syriac milieu since his time. The possibility of the earlier date for the composition suggested previously in scholarship became a much-cited argument. E. A. Wallis Budge, the author of the English translation of the Cave of Treasures, published in 1927 and based on a single manuscript from the British Museum (Ms. Add. 25875, representing the so-called Eastern recension), noted that even though “it is now generally believed that the form in which we now have it is not older than the VIth century”6 and even though the attribution to this great fourth-century Syriac poet is wrong, “if not written by Ephrem himself, one of his disciples, or some member of his school, may have been the author of the book.”7 In other words, Budge strongly suggested fourth-century Ephremian connections for the original core of the composition, while the present text took shape in the sixth century or later. The assumptions of the wide chronological range for the date of the composition – the fourth to the sixth century – still occasionally surface in the scholarship, often citing Budge.8 Su-Min Ri, the editor of the CSCO publication of the Cave of Treasures and its French translation (1987), again speaks about the mid-fourth century as the date of the original work, while the final reduction is assumed to belong to a sixth-century “Nestorian” writer.9

Scholars who ventured into the topic of the primordial language in early Christian and Jewish thought often took the early date of the Cave of Treasures for granted. Josef Eskhult treats Ephrem the Syrian as a founding figure of the entire Syriac exegetical tradition, whose representatives opposed the hypothesis of Hebrew primordiality and asserted this status for the Syriac language. Eskhult’s views are primarily based on the attribution of the Cave of Treasures to Ephrem shared by “almost all manuscripts” and the fact that the work prioritizes Syriac so emphatically.10 Eskhult strongly suggests that the idea of Syriac primordiality, as manifested in the Cave of Treasures, goes back to Ephrem or at least to the otherwise undefined circle of “his Syrian successors.” He acknowledges, however, that the passage about the consequences of the Babel confusion in Ephrem’s authentic Commentary on Genesis “leaves the question open.” The Commentary mentions that, at Babel, all people “lost their original language, which was lost by all the nations, with one exception.”11 But, as Eskhult notes, the text does not specify “which nation, the Hebrew or the Syrian” preserved the original tongue. Similarly, Milka Rubin mentions that “leaning upon two great figures, Ephraem the Syrian and Theodore of Mopsuestia, Syriac writers are almost unanimous in their claim that Syriac was the primordial language” and that this position “is almost the rule amongst the Syriac writers.”12 She relies on the dubious attribution of the work to Ephrem, the ambiguity of the corresponding passage in his Commentary on Genesis, and the absence of direct testimony in Ephrem’s authentic works. Moreover, she refers to later Syriac writers, starting with Michael the Syrian (twelfth century) and ʿAbdishoʿ bar Brikha (late thirteenth–early fourteenth century), who mentioned Ephrem among the supporters of the idea of Syriac primordiality.13

By contrast, Sergey Minov asserts that “nowhere in his authentic writings does Ephrem promote the idea of Syriac as the primeval language.” Citing the same Ephrem’s passage from the Commentary on Genesis about this enigmatic single nation – the Hebrews or the Syrians? – that preserved the primordial tongue, he argues that “in the fourth-century intellectual context, where Hebrew was the only attested candidate in discussions on the primeval language, such an ambiguous statement should almost certainly be understood as relating to this language and not, for instance, to Syriac.”14 Minov comments on the scholarly tendency to downplay the significance of the idea of Hebrew primordiality among late antique Syriac writers and to anachronistically project the post-seventh-century statements of Syriac priority back into the earlier periods: “In fact, the only Syriac writer to affirm the primacy of the Syriac language during this period is the author of [the Cave of Treasures].”15

I share Minov’s conviction that most likely Ephrem has nothing to do with the idea of Syriac primordiality ascribed to him later. Yet, the tendency to attribute these views to Ephrem or his disciples, attested among some scholars, shows that a detailed analysis of relevant passages in Ephrem’s corpus about the primordial tongue remains a desideratum. Thus the present article aims to read Ephrem closely, contextualize his ideas in a broader intellectual landscape of the fourth century, and explore any certain, uncertain, and undoubtedly ambiguous testimonies of what he may have thought about the primordial language. I hope that the deep dive into Ephrem’s discussion on the tower of Babel and the confusion of languages will clear up the persistent misconception that Ephrem can be taken for granted as a champion of Syriac primordiality.

A few preliminary remarks on Ephrem’s take on languages are needed before discussing the specific passages that mention Babel and the confusion of tongues.16 First, for Ephrem, whenever the concept of “confusion” (ܒܠܝܠܘܬܐ) is employed to describe the actions of God or any natural processes governed by God, this is, in a way, a misnomer. Such actions and processes are only confusing when people cannot make sense of them and comprehend the ultimate order behind them. Any such “confusion” reveals divine providence. In one of the Hymns Against Heresies, Ephrem argued:

The appearance of his [God’s] acts is very confusing for us, and as if without the order, he makes [some] poor and again rich; yet this confusion is entirely in order, just as the stars are apparently confusing, and yet they are in order, every single one, and according to the [divine] command they are set.17Ephrem did not refer to the Babel confusion of tongues specifically here. His primary argument is against various stripes of magicians, fortune tellers, and astrologers. However, by extension, the description implies that God’s intervention at Babel was a careful and premeditated process as well, rather than an act of mixing up languages “as if without the order.” The fact that Genesis 11:1–9 could be read and was read in this way in the Syriac milieu is evident, for example, from Jacob of Sarug’s homily On the Tower of Babel.18

Second, the semantic range and etymology of linguistic and ethnic names may provide an additional clue for the discussion because it helps locate Ephrem in his contemporary cultural context. As far as we know, in his extant works, Ephrem never mentioned Aram, who, according to the table of nations in Genesis 10, was a son of Shem and a grandson of Noah and whose name was often taken as an eponym for the Aramaic language and people. Ephrem, however, occasionally referred to “Arameans” (ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ).19 The term was originally a self-definition of those we would call “Syriac speakers,” but it gradually acquired a range of meanings beyond simply a designation of the ethnic group. With the increasing Christianization and Hellenization of the region, Syriac-speaking Christians chose to describe themselves as “Syrians,” while the term “Arameans” started to function as a Syriac equivalent of Greek Ἕλληνες or τὰ ἔθνη in a Christian sense.20 It referred to “gentiles” or “nations,” as opposed to the Hebrews/Jews, just as Beck’s note reminds us: “Das Wort ‘Aramäer’ hat im Syr. die Bedeutung ‘Heiden’ gewonnen.”21

On the other hand, Ephrem explicitly stated that “the Hebrews [are descended] from Heber.”22 The significance of this statement becomes apparent if we take into account the wider late antique polemics about who – Heber (Genesis 10:21-25 and 11:14-16) or Abraham ha-ʿibri (Genesis 14:13) – was instrumental in preserving the original tongue and after whom the language and the people were named “Hebrew.” This issue became a focal point of Jewish–Christian cultural debate and contributed to consolidating their corresponding religious identities. The basic meaning of Abraham’s appellation ha-ʿibri in Genesis 14:13 is “traveler,” “emigrant,” or “one who crossed something.” Abraham was so-called since he came from native Chaldea to the foreign land of Palestine, crossing the Euphrates river. The appellation was also taken as the first attestation of the ethnonym “Hebrew.” Generally speaking, those Christians who accessed the biblical text via the Septuagint preferred the Heber eponymy because it was prompted by its rendering of the passage Genesis 14:13 as “Abraham the traveler” (περατής) and not “Abraham the Hebrew.”23 So did the readers of Vetus Latina versions, where transfluvialis and transitor are attested, both referring to “crossing.”24 The alternative Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible – Symmachus and possibly Aquila – read Ἐβραῖος in this place, and likewise, in the Vulgate, Jerome chose to translate Abram Hebraeus, “Abram the Hebrew.”25 Yet most Graeco- and Latinophone Christians did not suspect that the Hebrews had been named after Abraham unless they were familiar with the Hebrew text or Jewish exegetical traditions.26 By contrast, this was by far a preferable etymology for rabbinic writers because the verses Joshua 24:2 and 24:15 suggest that the immediate ancestors of Abraham, including Heber for this purpose, were idolaters and worshipers of other gods. Therefore, Heber is not worthy of being an eponym for the Hebrew nation and language.27

The Peshitta Old Testament preserves the original root of Abraham’s appellation ha-ʿibri attested in Hebrew Genesis 14:13. The Peshitta’s corresponding passage has ܥܒܪܝܐ, which, with certain exegetical ingenuity, could be read as both “Hebrew” and “one who crosses” or “one who passes over.”28 By itself, however, ܥܒܪܝܐ unambiguously refers to the ethnonym “Hebrew” due to its gentilic ending -aya. The significance of this observation is that whatever the level of Ephrem’s familiarity with Jewish exegetical traditions was,29 and although the Peshitta’s Genesis 14:13 mentions “Abraham the Hebrew,” Ephrem supported Heber’s eponymy. By the end of the fourth century, the preference for the Heber-centered vision became mainstream in other Christian traditions.30 This preference usually goes “in a package” with the acknowledgment of Hebrew as the primordial tongue. The point is not enough to claim that Ephrem shared the same opinion, but it allows us to suggest that he might have followed the same logic.

Third, Ephrem did not identify the primordial language with the language of God, as did most rabbinic writers of the time, who argued that Hebrew was both.31 Similarly to Gregory of Nyssa, who in his anti-Eunomian polemics asserted that all languages are property of human nature and none of them can be an attribute of God,32 Ephrem also poetically addressed the problem of the ontological gap between the nature of God and the capacity of human languages to describe it. He pointed out that language is something that belongs to humans, but God voluntarily made use of it to communicate with humankind and to become more approachable:

…if he had not put on the names of these very things, he would have been unable to speak With our humanity. With [what is ours], he drew near to us. He put on our names, to put on us His way of life.33Elsewhere, Ephrem suggests that before Babel, people could communicate with God without the mediation of a spoken tongue. He ascribed to Moses the remark that “the Creator had been manifest to the mind of the first generations, even up until the [generation of] the tower,” when this intimacy was lost.34 Again, these observations do not help to define Ephrem’s views on the primordial language conclusively. However, they demonstrate that whatever the original tongue might be, Ephrem would have been invested in a possible competition between Hebrew and Syriac for originality, ontological power, and relative prestige, only to a degree to which both remained inherently human languages. None of them claimed a special status of God’s language.

The tower of Babel and the confusion of tongues appear several times in Ephrem’s compositions.35 In addition to the most detailed exposition in the Commentary on Genesis, which we mentioned above and for which the current scholarly consensus is that it is Ephrem’s authentic work, he referred to Babel twice in the Exegetical Sermons, once in his Hymns on Faith, Against Heresies, Hymns on Nativity, Hymns on Virginity, and Carmina Nisibena. For Ephrem, the biblical passage Genesis 11:1–9 clearly describes the event that led to the multiplication of tongues and started linguistic diversity, the moment when the primordial unilingualism of humankind turned into many languages spoken by Noah’s grandchildren.

The Hymns on Faith is Ephrem’s longest collection of hymns. It likely includes individual pieces and smaller cycles written in different moments of his literary career, which may have circulated initially independently and later became a unified whole.36 The collection most directly addresses the issues related to the fourth-century Christological controversies. The underlying motive of many hymns in the cycle is the limits of human knowledge regarding Christ’s divinity and how he was begotten by God the Father. According to Ephrem, pious silence is always preferable to gratuitous theological debate and inappropriate inquiry into divine matters.37

The passage in which Ephrem referred to the tower of Babel appears in Hymn 60:

[60:11] Who will not rejoice? For if these titles Correspond to one another – earth to Adam, Eve to life, Peleg to division, And Babel to confusion (for they came to confusion) – Let us quiet the disorder. Receive in order The threefold names! [60:12] From Babel learn: there Three went down and confused [the tongues], for he said, “Come (pl.)! Let us go down,” And this no one could say to only one. To one, [he would say] “Come (sing.)! Let us go down.” The Evil One, with the tongues That were confused, has babbled in our day – [In] the Church instead of Babel.38The second stanza cites Genesis 11:7. Similarly to his treatment of the Babel episode in the Commentary on Genesis,39 Ephrem asserted that the plural imperative form used in God’s direct speech “Come (plur.: ܬܘ), let us go down,” refers to all three members of the Trinity who participated in the event. Otherwise, if only the Son or the Spirit took part in this action with God the Father, the singular form ܬܐ would have been enough. Similarly, the Commentary on Genesis stated that “neither the ancient nor the more recent languages were given without the Son and the Spirit.” The third instance that I am aware of in which Ephrem emphasized the plural form of the verb “Come!” in Genesis 11:7 occurs in one of his Exegetical Sermons: “One [of the prophets] said: I heard from the Father when he said: ‘Come, let us go down to Babel and divide languages in it [Babel]’.”40 The quotation appears in this sermon’s intense crescendo of prophetic statements. Each starts with “One said…” followed by yet another memorable line from the Bible or a paraphrased reference to a biblical event. The Babel episode is not a focal point of Ephrem’s exegetical efforts here.

The plurality of divine actors equally participating in this Old Testament episode became important in the context of fourth-century Trinitarian polemics. This theme diverges from the interpretation suggested just a little over a century ago by Origen in his Homilies on Numbers (c.245), who, following the Jewish precedents (e.g., the Hebrew Testament of Naphtali 8.6), asserted that God was addressing angels.41 The remark on the Holy Spirit became especially important in the context of the debates in the late 360s–early 370s, when several Greek writers, including the Cappadocians, emphatically affirmed the Holy Spirit’s divinity.42 The reading of Genesis 11:7, referring to the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, soon became commonplace in Christian exegesis across different literary and confessional traditions.43

Ephrem made another exciting move here. He drew parallels between the Babelites of old and “the Evil One” of his days, babbling with confused tongues. At first, “the Evil One” seems to allude to the devil. But the subsequent zooming in on such specifics as “in our day” and “in the Church instead of Babel” implies a certain unnamed human actor or actors. However, Ephrem’s poetic language is more likely to encompass all those meanings. “The Evil One” of the cosmic drama still speaks through the contemporary leaders of heterodox opinions, according to Ephrem. The take-away point for our discussion about the primordial language is that the increasing importance of the line Genesis 11:7 in the context of the Trinitarian polemics drew away one’s attention from the historical reading of the passage. The overwhelming focus on theological underpinnings eclipses the potential opportunities for linguistic speculations.

We see the same tendency among fourth-century Greek writers. Very few voices pondered the primordial language in the period between Eusebius and Chrysostom, probably because prominent Greek theologians of the time, such as Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa, were engaged in anti-Eunomian polemics. As a result, they took a very different stand on languages and linguistics.44 Among other things, this eventually brought Gregory to reject Hebrew primordiality altogether. He favored the idea of primordial unilingualism but refused to make a judgment concerning the identity of the first language because of a lack of scriptural evidence.45 According to Gregory, Hebrew was just one out of many other ethnic tongues and a relatively recent invention: “Some of those who have studied the divine scriptures most carefully say that the Hebrew language is not even ancient in the way that the others are, but that... this language was suddenly improvised for the nation after Egypt.”46 Gregory repeated an argument employed by several Hellenistic critics of Judaism and early Christianity. He referred to Psalm 80.6, “When they went forth from the land of Egypt, he heard a language that he did not know,” as biblical proof that Hebrew emerged during the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt.47 This scriptural passage was the one Origen rejected, arguing for the opposite cause in his polemics against Celsus.48 Ephrem may have shared the same line of thought as contemporary Greek Christian writers, namely, that the discussions about the primordial language may be superfluous and counterproductive. 49 This also fits well his overall stance against unnecessary inquiries and empty curiosity. There is one significant difference, though, between him and Gregory. As seen in his Commentary on Genesis, Ephrem asserted that one (unnamed) nation preserved the original tongue after the confusion at Babel, while Gregory did not seem to entertain such an option.

A few words need to be said about the first stanza in the quoted passage. It presents a poetical and etymological exercise that may be potentially helpful for discussing the identity of the primordial language. Ephrem alludes to the names (ܟܘܢܝ̈ܐ or ܫܡܗ̈ܐ) and their correspondence to the things they describe. He encourages readers to rejoice, “quiet the disorder,” and “receive in order” divine names. The controversy about the divine names fits the stage of the Trinitarian debates in the 360s. Ancient discussions about the correctness of names went back to Plato and his famous dialogue Cratylus and were later carried on by Hellenistic and Jewish thinkers.50 The main idea was that language that can demonstrate the correspondence between words and the essence of the things they describe is ultimately “correct.” In the Judeo-Christian context, such a language would be the most likely candidate for primordial status. The discussions routinely evolved around etymological and pseudo-etymological arguments. Ephrem’s text highlights the parallels between ܐܕܡܬܐ and ܐܕܡ (earth and Adam), ܚܘܐ and ܚܝܘܬܐ (Eve and life), ܦܠܓ and ܦܘܠܓܐ (Peleg and division), ܒܒܠ and ܒܘܠܒܠܐ (Babel and confusion). These parallels work reasonably well for his Syriac.

Such etymological inquiries in biblical names were common among rabbinic and Christian scholars who argued in favor of Hebrew’s primordiality. For example, composers of the Genesis Rabbah readily pointed out the linguistic correspondence between the Hebrew words for man (ʾish) and woman (ʾishah) in Genesis 2:23 “She shall be called woman, because she was taken out of man.”51 They meant to demonstrate that the linguistic logic of Hebrew coincides with the ontological logic of creation, i.e., the creation of woman from man, and to confirm the unique position of Hebrew among other idioms. This reasoning of Rabbinic scholars was taken up by Christian writers, such as Eusebius of Emesa (c.300–359), who referred to precisely the same argument, i.e., the ʾish–ʾishah pun from Genesis 2:23.52 Moreover, he asserted that the biblical characters before the Flood had Hebrew names (this claim is also attested in Rabbinic literature). In his Preparation for the Gospel, Eusebius of Caesarea (c.263–c.339) examined several biblical names in Hebrew and demonstrated that they correspond to the essence of the things they describe. He summed up, “anyone diligently studying the Hebrew language would discover great correctness of names current among that people.”53 By contrast, just a century later, Theodoret of Cyrrhus (393–c.466), who became the only significant Greek Christian author of the time to argue for the Syriac alternative to the Hebrew primordiality,54 explicitly asked in his Questions on the Octateuch: “Which is the most ancient language?” To answer this question, he chose a reasonably standard approach – the etymology of biblical names such as Adam, Cain, Abel, and Noah. However, the outcome was a bit unusual. Theodoret argued that these etymologies work best for Syriac, not for Hebrew, as had been assumed by many Jewish and Christian writers.55 It is tempting to suggest that Ephrem in the Hymn 60 on Faith followed the same logic. The etymological connection between the pairs of biblical words he mentioned works well in his native Syriac. I do not think, however, that this is what Ephrem implied here. Considering the close relationship between Syriac and Hebrew and the speculative character of ancient etymologies, the very attempt to derive the biblical names solely from Syriac to the exclusion of Hebrew is problematic.

Ephrem’s cycle of hymns Against Heresies has been traditionally dated to the last decade of his life, the so-called Edessan period,56 though the most recent discussion of their date and milieu suggests a possibility that some of them were composed back in Nisibis prior to 363.57 Ephrem polemically attacks Mani, Marcion, Bardaisan, and the like in this cycle. In hymn 5, he takes a stand against unnamed “magicians” and “augurs”:

The confused sons of Babel confused our hearing, In the beginning, the languages were confused inside her [Babel’s] inner part. Magicians and augurs within her [Babel] are confused again. Babel, which confusions confused, Who gives to her [Babel] his soul and his hearing, The legion skips in him, and dances, and leaps in him.58The reference to the biblical Babel functions as an underlying metaphor for this stanza. The confusion of tongues in Babel becomes an ultimate archetype of all confusion, past and present. Similarly to the Hymns on Faith passage analyzed above, Ephrem compares those who were “confused” in his time – fortune tellers, astrologers, wizards, and various kinds of heretics – to “the confused sons of Babel,” whose languages were confused. Interestingly enough, Ephrem speaks about their “languages” in the plural and is not concerned with the single primordial tongue prior to the event. Although the image of Babel as the place of confusion is central in this stanza of the hymn, it is not especially helpful for discussing the identity of the pre-Babel language in Ephrem.

Typology of the biblical tower of Babel, confusion, and division of languages is rich and polysemantic.59 It has great potential and can be twisted in different ways. On the one hand, it can get a positive spin and designate something unique, spectacular, and grandiose. On the other hand, the Babel confusion is unavoidably a story about disruption, failure, and disaster. One can blame the devil, human sinfulness, or their passions, hubris, and disobedience, but the overall picture is bleak. It was common for early Christian writers to use Babel as a typos for any biblical or post-biblical catastrophe attributed to demonic tricks or a human error.60 Additionally, once the Pentecostal episode from Acts 2:2–12 started to be interpreted as describing the apostles’ xenolalia, i.e., the ability to speak actual foreign languages miraculously distributed among them, most Christian interpreters exegetically linked it to the Babel account. As a result, these two very distinct biblical narratives began to tell the single story about a great cosmic drama of doing and undoing, of introducing linguistic diversity and rendering it invalid, of the beginning of division and the restoration of unity, which on both ends was mediated by the divine will.61

Ephrem followed the first option in one of the Hymns on Nativity. The cycle offers “a developed theology of the incarnation and mariology in the context of a strong anti-Jewish polemic”62 and is “an extraordinarily rich source of early Christian typological exegesis.”63 In the first hymn of the cycle,64 he employed a great variety of Old Testament typoi that anticipate the arrival of Jesus. Turning to Babel, Ephrem presented “the tower that the many built” as a symbol of “the One...[who] went down and built on the earth the tower that reached the heaven.”65

Interestingly enough, Ephrem skipped mentioning the linguistic phenomena that accompanied the building of the tower and the eventual abandonment of the construction. Instead, he explored the opportunities that the image of a single and magnificent structure offers as a metaphor (typos or symbol, ܐܪܙܐ) for Christ and his Gospel. The identity of the primordial language is not of Ephrem’s slightest interest here.

However, two lines later, Ephrem mentioned that “in the days of Peleg, the earth was divided into seventy tongues; this anticipated the One who divided the earth for his apostles through the tongues.”66 The verse linked the Babel confusion of tongues to the Pentecost event when the fiery tongues of the Spirit endowed each of the apostles with the ability to speak in different languages. Thus, languages were divided among the apostles, similarly to the division of the languages at Babel – the typos that anticipated the Pentecostal miracle.

Ephrem explores the same imagery and typology elsewhere in his works. In one of the Hymns on Virginity, he also mentioned that the earth was divided into seventy languages at Babel. This division foreshadowed another division of the earth among the apostles through the tongues. Ephrem’s Hymns on Virginity is a heterogeneous collection composed of several smaller cycles, each united by a single theme and melody and several stand-alone hymns. Hymn 40, in which Ephrem referred to Babel, is one of those individual poems. Its central themes are praising the Lord, the people’s expectations for the Messiah in the past age, and the current struggle against the faithless and disputers. The verses about Babel are partially lost, and the best attempt to recover the texts yields the following:

(R11) The High One came down and confused voices and languages That were agreed toward harm, and he taught… He gave the disciples the multitude [of languages] That their truth would be as a typos… … (Š12) The falsehood… in it That he considered the confusion; he scattered the people; And he destroyed the tower … disputants; They divided… that the truth would not be built The tower of our salvation. 67As far as we can judge, there is a tightly crafted polysemantic system of images and their opposites – falsehood and truth; the Babelites, the apostles, and the new disputants; the unity of faithful and scattering around of sinners; the division of tongues at Babel and the one on the day of Pentecost; the tower of harm and that of salvation. The rhetoric is aimed at the disputers of the current age who behave in the same arrogant and senseless manner as the old tower-builders at Babel. The “Most High” who punished sinful Babelites and confused their tongues is also the one who endowed his disciples with the gift of multiple languages. The truth that the apostles received became a promise of the future salvation of those who separate themselves from the falsehood of confusion and hostilities. In this complex typological network of signs and symbols, the question of the identity of the pre-Babel language was outside Ephrem’s exegetical framework. The image of Babel has potential for his purposes, but its historical linguistic aspect is not his priority.

Here we should briefly comment on passages where Ephrem discussed the Pentecost account but not the Tower account. The fragments relevant to apostolic speaking in tongues from Ephrem’s Commentary on Acts are preserved only in the Armenian Catenae. The state of the composition is such that virtually everything – the attribution to Ephrem, the language of the original, the dates of its translation, and further editing – can be questioned.68 Ephrem’s Commentary on Pauline Letters also exists only in the Armenian translation, and given the problem of authenticity of the Armenian corpus associated with his name, this testimony is again uncertain.69 Among Ephrem’s texts preserved in original Syriac, one of the Hymns on Paradise recounts the Pentecost event but provides little information about the apostles speaking in tongues.70 The phrase “sending forth the tongues after his ascension” appears in the Hymn on Nativity 25.71 However, none of these passages indicate what the primordial language was.72

The passage in which Ephrem attributed the Babel disaster directly to demonic tricks occurs in one of his Carmina Nisibena, a set of poems about his native city of Nisibis, the gradual maturing of its Christian community, its bishops, and three dramatic sieges laid by the Persian army in the 330s–350s. In poem 41, Satan speaks directly to Jesus and takes responsibility for the construction at Babel:

I enhanced my racings with the speed, and I overrun them. I was fighting. The clamor of many was armor to me. I rejoiced in the noise of people that gave me a little room, That the vehemence of many was harsh; with the force of many I erected the great mountain, the tower that reaches heaven. If they were fighting against the height, How much more they will be victorious over the one who fights on earth.73The devil boasted that he established “the great mountain” of the Babel tower that stretched up to heaven as his way to mobilize the forces of multitudes to fight for him. However, the poem’s image of the tower of Babel has little to offer for the current discussion of the primordial language.

Interpretations of the Babel story occasionally take an unusual turn in Ephrem’s poetical legacy, revealing some lesser-known directions of the Old Testament exegesis. In his cycle of the Exegetical Sermons, Ephrem suggested that three races originated from Noah – namely, the giants, humans, and dwarfs. The giants were those who built the tower and whose tongues were confused:

(2.476) The giants were dissolute, When the law was not yet set, And the Flood overflowed and drowned The dissolute men and women. Ten thousand voices of the law Are crying out to us in the entrances of our ears, And our intelligence is still not ashamed That it would submit and learn the truth. The giants built the edifice, And their languages were confused. We are erecting the mountains of sins, And the word of our mouth continues to exist.74Ephrem built the dramatic contract by piling up the examples of what had been done by the dissolute race of giants of ancient times, including their well-deserved punishments and the eventual destruction, on the one hand, and the continuing wrongdoings of the current generation, on the other hand. The contrast is intensified to the highest degree because people of the present age continue to behave senselessly, despite having the warning of the law, the lessons of the past, and the promise of the future truth and submission.

The passage demonstrates Ephrem’s familiarity with Jewish and Hellenistic apocryphal traditions commenting on Gen. 6:4, which tells of “the mighty men of old” or giants, born from the marriage of “the sons of God” and “the daughters of men.” In Gen. 10:8–9, Nimrod, who was later associated with the tower’s construction, is named “a mighty one on the earth” and “a mighty hunter.” The idea that there had been a certain pre-Babel race of giants was attested in Greek historians of the Hellenistic and Roman era – in Abydenus’ now-lost History of the Chaldeans (c. 200 BCE), which probably was derived from the history by Berossus (c. 300 BCE, Babylon), and in Alexander Polyhistor (first century BCE, Rome). In his Chronicle and Preparation for the Gospel 9.14 and 9.17, Eusebius of Caesarea cited the opinions of Abydenus and the earliest Hellenistic Jewish historian Eupolemus that the giants built the tower of Babel.75 Ephrem likely drew on the same Jewish Hellenistic tradition when he mentioned the giants in his sermon.

With this last example, we have exhausted the list of references to the tower of Babel and the confusion of tongues attested in Ephrem. The most explicit discussion of the Babel episode occurs in his Commentary on Genesis, where Ephrem presented it as the termination of the original unilingualism and the beginning of linguistic diversity. He emphasized that “the whole earth had a single language” and that Noah’s grandchildren “received” their tongues at Babel before being scattered worldwide.76 Seventy-two different nations came from seventy-two grandsons of Noah, speaking their respective languages. As Ephrem noted, all of them, with a single exception, lost their shared primordial tongue. Who was this exception? Ephrem did not point to Heber and his descendants directly. His story’s primordial language remains nameless, turning into an invitation to further speculative suggestions. It is as if Ephrem intentionally left such a playful remark, meaning to puzzle scholars today.

Why did he not give any further details? To start with, his Commentary on Genesis is a very peculiar document. Ephrem probably wrote it during the last decade of his life in Edessa, where he moved after his native Nisibis was surrendered to the Persians. In Edessa, Ephrem encountered a wildly diverse multireligious and multiconfessional community and saw his urgent task in supporting the orthodox cause.77 The exercise in reading his Commentary on Genesis reminds one of an overheard phone conversation, in which we listen only to one interlocutor, namely, Ephrem, and should do our best to supplement the responses on the other end, namely, those by the followers of Bardaisan, Mani, and Marcion, with whom Ephrem debated, in a way that would meaningfully reconstruct the rest of the dialogue.78 This polemical focus explains both – the unbalanced structure and sometimes curious content of the Commentary. Not all chapters of Genesis received equal attention. As Edward Mathews and Joseph Amar note, “The entire first half of the Commentary on Genesis is devoted to only three pericopes: the six days of creation; the fall of Adam and Eve; and the flood that occurred in the days of Noah.”79 The exposition of these passages had a greater theological significance for Ephrem and his fight against heterodox ideas, particularly against the teaching of Bardaisan. After Genesis 4, Ephrem’s Commentary largely paraphrases the biblical text by adding some dramatic elements to the action.80 Significant portions of the narrative are summarized or skipped over. It is the part to which the story about the tower of Babel belongs. Since the socio-historical implementations of the alleged starting point of linguistic diversity had little importance for Ephrem’s opponents’ primeval history and mythological constructions, he did not feel the need to address the passage polemically in greater detail. Therefore, he only reported its content briefly.

Does this mean that Ephrem was outright not interested in languages and communication? His works’ various metalinguistic remarks and comments demonstrate that this is not the case. He typically attends to forms and modes of expression and communication. He introduces metalinguistic remarks in his descriptions of biblical events, even where the original scriptural passage would not mention anything about languages. In the same Commentary on Genesis, Ephrem narrated the story of Joseph’s brothers who came to Egypt for food during the famine in Judea (Genesis 42). Joseph concealed his true identity and acted as a high Egyptian official. According to Ephrem, when Joseph accused his brothers of being spies, their rebuttals involved language issues: “They answered and said, ‘We do not even know the Egyptian language so that, by speaking Egyptian, we might escape notice and deceive the Egyptians. That we dwell in the land of Canaan you can learn from our offering... That we are completely ignorant of the Egyptian language and do not wear the garb of Egyptians also testifies to our truthfulness.’”81 Ephrem’s text closely paraphrases Genesis 42, which at some point specifies that Joseph spoke Egyptian and an interpreter mediated his conversations with the brothers (Gen. 42:23). However, Ephrem himself was responsible for mentioning the Egyptian language as an argument against the allegation that the visitors were spies. It is his original addition to the flow of the biblical story – logically plausible but lacking the direct scriptural foundation.82

Another fascinating insight – this time into the linguistic situation in Paradise – occurs in Ephrem’s Commentary on Genesis 3. Ephrem inquired into the serpent’s language while speaking to Eve (Gen. 3:1). He considered four options: first, that “Adam knew the serpent’s own language”; second, that “Satan spoke through [the serpent]”; third, that “the serpent asked the question mentally, and speech was granted”; or fourth, “Satan asked God that speech should temporarily be granted to the serpent.”83 For our discussion, it is not essential which option Ephrem preferred, but the exceptional level of attention he paid to linguistic codes and channels of communication is noteworthy. Ephrem demonstrated a keen interest in tangible details and the very mechanics of verbal interaction.

Similarly, we note unexpected remarks on languages in Ephrem’s hymns and homilies on New Testament passages. He added, for instance, that when Jesus healed the deaf and mute people (Mark 7.31-37) they “hear and speak languages (plur.) they had never learned.” This was meant to anticipate the apostolic speaking in every language.84 The relevant Gospel passages, including the Diatessaron, do not mention anything about languages spoken by the former mute. The detail seems to appear out of Ephrem’s love for typological interpretation, but it also reveals that the issue of language was permanently present in his mind. Elsewhere, Ephrem presented Jesus as a newborn baby and then a prisoner before Herod (Luke 23:11). Jesus is silent in all cases and yet “sang in every tongue.”85 Jesus was the infant “in whom all our tongues were hidden”86 and in whom “all tongues resided.”87 These images are again a strong indicator of Ephrem’s attentiveness to languages. Despite the concise character of his commentary on the Babel episode and the utter ambiguity of his reference to the preservation of the primordial tongue, there are multiple other examples in his works that evidence his keen awareness of the world’s multilingualism and his constant questioning of how languages operate. Whenever it was essential for his multilayered typological exegesis, he never missed a chance to apply this vivid interest in languages and communication to the biblical situations he analyzed.

The opposite, however, appears to be also true. Whenever the biblical passage does not lend itself to typological interpretation or a polemical cause, the purely historical or socio-linguistic reading is reported by Ephrem, but only factually and succinctly. This seems to be the case with the primordial language. Moreover, Ephrem’s lack of interest in the original tongue is an indirect testimony to his siding with the mainstream Christian opinion of the time, namely that it was Hebrew. If he had been a champion of Syriac primordiality, he would not have missed a chance to emphasize that when he interpreted Genesis 11. Ephrem is usually quite explicit about whatever polemics he is engaged in, and that polemic is absent here.

One final piece of the puzzle is Ephrem’s reference to Hebrew in the episode about Joseph and his brothers in Egypt from his Commentary on Genesis discussed above. When Joseph eventually revealed his identity to his brothers, he started to speak to them “in the Hebrew tongue” (ܒܠܫܢܐ ܥܒܪܝܐ).88 Therefore, if Joseph and his brothers spoke Hebrew as their family language, according to Ephrem, one can assume that their immediate ancestors, Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham, probably did use this language as well. But was this the language and the nation that were “a single exception” spared during the confusion at Babel? According to our take on Ephrem’s thought, yes. However, the counterargument may be borrowed from Theodore of Mopsuestia (c.350–428). Although we have only indirect and later testimonies about his linguistic ideas,89 according to Yonatan Moss’s reconstruction, Theodore argued that Syriac was the original tongue of humankind and that Hebrew appeared as a result of involuntary corruption of Abraham’s native Syriac through the contact with the language of Canaan when he moved there from Chaldea.90 If one imagines Ephrem following the same logic, the remark that Joseph and his brothers spoke Hebrew does not qualify as a testimony to the primordial language. There are, however, too many “ifs” in this scenario. First, Ephrem most likely did not follow the same logic. Second, Theodore’s views are very uncertain. As Sergey Minov mentions, “given the late nature of all these witnesses and the lack of unanimity on this issue among East Syrian transmitters of the Theodoretan legacy, it seems impossible at the present time to satisfactorily resolve the question of the authenticity of this tradition.”91

The remarks on the tower of Babel and the confusion of tongues in Ephrem’s Exegetical Sermons, Hymns of Faith, Against Heresies, Hymns on Nativity, Hymns on Virginity, and Carmina Nisibena do not go as far as to mention explicitly or even indirectly imply the identity of the primordial tongue. The Babel episode often serves Ephrem as a virtually endless source of symbols and typoi – joined in multidimensional combinations and capable of lending themselves to different theological arguments and poetical imagery. This paper deliberately avoids making generalizing statements about Ephrem’s exegetical method and pigeonholing him in terms of “allegorical” or “literal” traditions or schools but instead leans toward the statement that Edward Mathews and Joseph Amar put so beautifully: “His theological method, often labelled symbolic theology, is an intricate weave of parallelism, typology, names, and symbols. In the creative application of these tools, Ephrem displays a genius admirably suited to express the various paradoxes of the Christian mystery.”92

While socio-linguistic and language-related historical speculations seem to be tangential to Ephrem’s poetical and theological agenda, this approach brings him close to the visions and thoughts of contemporaneous Greek writers, primarily the Cappadocians. Like Gregory of Nyssa and Basil of Caesarea, Ephrem presented language as an attribute of human nature. In his magnanimity, God may condescend to use any language to be more approachable to people. Ephrem’s interest in the plurality of actors in Genesis 11:7 places him in the 360s–370s context of the Trinitarian debates about the Holy Spirit’s divinity. He supports the idea that the Hebrews were named after Heber, reflecting the consensus of Christian writers on this issue. All these observations usually go together with acknowledging Hebrew as the primordial tongue. Although Ephrem never directly stated the primacy of Hebrew, and his speculative etymology of biblical names works equally well for Hebrew and Syriac, he likely shared the same ideas about the early linguistic situation. He never explicitly mentioned Syriac as the primordial tongue, and this absence is much more telling than the fact that he skipped over mentioning Hebrew.

It is true that authentic writings of late antique Syriac authors, including but not limited to Ephrem the Syrian, are surprisingly equivocal whenever it comes to the identity of the pre-Babel language. Their views can be reconstructed only to a degree by collating the bits of information from indirect statements. However, it is essential to disentangle this problem to understand the genesis of the idea about the primacy of Syriac. This tremendously powerful and unprecedented identity statement on behalf of Syriac Christian elites attested in the Cave of Treasures and then, from the eighth century, on different sides of the post-Chalcedonian confessional divide. However, nowhere in his works does Ephrem seem to invest in these polemics.

Bibliography

- Baxter, Timothy M. S. The Cratylus: Plato’s Critique of Naming . Leiden: Brill, 1992. .

- Baehrens, W. A. Origenes. Homilien zum Hexateuch in Rufins Übersetzung. Teil 2: Die Homilien zu Numeri, Josua und Judices . Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller der ersten drei Jahrhunderte 29, Origenes Werke 7. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1921. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen De virginitate , CSCO 223–224, SS 94–95. Leuven: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1962. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermo de Domino Nostro , CSCO 270–271, SS 116–117. Leuven, Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1966. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones de fide, CSCO 212–213, SS 88–89. Leuven: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1961. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers: Sermones II , CSCO 311–312, SS 134–135. Leuven: Secretariat du CorpusSCO, 1970–1973. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Ephrem: Carmina Nisibena, CSCO 240–241, SS 102–103. Leuven, Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1963.

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Ephrem: Hymnen contra haereses, CSCO 169–170, SS 76–77. Leuven: L. Durbecq, 1957.

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Ephrem: Hymnen de fide, CSCO 154–155, SS 73–74. Leuven, L. Durbecq, 1955.

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Ephrem : Hymnen de nativitate. Epiphania , CSCO 186–187, SS 82–83. Leuven: Secretariat du CorpusSCO, 1959. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Ephrem: Hymnen de paradiso und Contra Julianum , CSCO 174, SS 78. Leuven: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1957. .

- Becker, Adam H. Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and Christian Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. .

- Borst, Arno. Der Turmbau von Babel: Geschichte der Meinungen über Ursprung und Vielfalt der Sprachen und Völker , vols. 1 and 2 . Stuttgart: A. Hiersemann, 1957–1958. .

- Brock, Sebastian and George Kiraz, eds. and trs. Ephrem the Syrian: Select Poems . Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2006. .

- Brock, Sebastian P. “Ephrem.” In Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay, .

- Brock, Sebastian P. “Jewish Traditions in Syriac Sources,” Journal of Jewish Studies 30 (1979): 212–232. .

- Burnet, J., ed. Platonis opera, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1900. .

- Butts, Aaron Michael, ed. and tr. Jacob of Sarug: Homily on the Tower of Babel . Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010. .

- Buytaert, É. M., ed. L’héritage littéraire d’Eusèbe d’Émèse, étude critique et historique . Leuven: Bureaux du Muséon, 1949. .

- Calabi, Francesca. The Language and The Law of God: Interpretation and Politics in Philo of Alexandria . Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998. .

- Collins, Marilyn F. “The Hidden Vessels in Samaritan Traditions.” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 3.2 (1972): 97–116. .

- Contini, Riccardo. “Aspects of Linguistic Thought in the Syriac Exegetical Tradition.” In Syriac Encounters: Papers from the Sixth North American Syriac Symposium , edited by M. Doerfler, E. Fiano, and K. Smith, 91–117. Leuven: Peeters, 2015. .

- Conybeare, Frederick C., tr. “The Commentary of Ephrem on Acts.” In The Beginnings of Christianity, Part 1: The Acts of the Apostles , ed. F. J. Foakes Jackson and Kirsopp Lake, vol. 3:373–453. London: Macmillan, 1926. .

- DelCogliano, Mark. Basil of Caesarea’s Anti-Eunomian Theory of Names: Christian Theology and Late-Antique Philosophy in the Fourth Century Trinitarian Controversy. Leiden: Brill, 2010. .

- Denecker, Tim. “Heber or Habraham? Ambrosiaster and Augustine on Language History.” Revue des etudes augustiniennes 60 (2014): 1–32.

- Dillon, J. “Philo Judaeus and the Cratylus .” Liverpool Classical Monthly 3 (1978): 37–42. .

- Dorival, Gilles. “Le patriarche Héber et la tour de Babel: Un apocryphe disparu?” In Poussières de christianisme et de judaïsme antiques: Études réunies en l’honneur de Jean-Daniel Kaestli et Éric Junod , edited by A. Frey, R. Gounelle, 181–201. Lausanne: Éditions du Zèbre, 2007. .

- Drijvers, Han J.W. “The School of Edessa: Greek Learning and Local Culture.” In Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-Modern Europe and the Near East, edited by Jan Willem Drijvers and Alasdair A. MacDonald, 49–59. Leiden: Brill, 1995. .

- el-Khoury, Nabil. “Hermeneutics in the Works of Ephraim the Syrian.” In IV Symposium Syriacum, 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature (Groningen-Oosterhesselen 10-12 September), edited by H. J. W Drijvers, R. Levanant S. J., C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink, 93–99. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987.

- Eshel, E. and M. E. Stone. “The Holy Language at the End of the Days in Light of a New Fragment Found at Qumran.” Tarbiz 62 (1992–1993): 169–78. .

- Eskhult, Josef “The Primeval Language and Hebrew Ethnicity in Ancient Jewish and Christian Thought until Augustine.” Revue des etudes augustiniennes 60 (2014): 291–347.

- Eskhult, Josef. “Augustine and the Primeval Language in Early Modern Exegesis and Philology.” Language & History 56.2 (2013): 98–119. .

- Eynde, C. van den, ed. Commentaire d’Ishoʿdad de Merv sur l’Ancien Testament , CSCO 126, SS 67. Leuven: L. Durbecq, 1950. .

- Féghali, Paul. “Influence des Targums sur la pensée exégétique d’Ephrem?” In IV Symposium Syriacum, 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature (Groningen-Oosterhesselen 10-12 September), edited by H. J. W Drijvers, R. Levanant S. J., C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink, 71–82. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987.

- Féghali, Paul. “Les premiers jours de la Création, Commentaire de Gn. 1,1–2,4 par Saint Ephrem.” Parole de l’Orient 13 (1986): 3–30. .

- Fischer, B., R. Weber, and R. Gryson, eds. Biblia sacra: Iuxta Vulgatam versionem. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1994. .

- Fraade, Steven D. “Before and After Babel: Linguistic Exceptionalism and Pluralism in Early Rabbinic Literature and Jewish Antiquity.” Diné Israel 28 (2011): 31–68. .

- Freedman, H. and Maurice Simon, eds. and trans. Midrash Rabbah, 10 vols . London: Soncino Press, 1983. .

- Gifford, Edwin, trans. Eusebii Pamphili Evangelicae Praeparationis. Oxford: Typographeo Academico, 1903.

- Griffith, Sidney H. “Ephrem the Exegete (306–73): Biblical Commentary in the Works of Ephrem the Syrian.” In Handbook of Patristic Exegesis , edited by Charles Kannengiesser, 1395–1428. Leiden: Brill, 2006. .

- Griffith, Sidney H. “Setting Right the Church of Syria: Saint Ephraem’s Hymns against Heresies.” In The Limits of Ancient Christianity: Essays on Late Antique Thought and Culture in Honor of R. A. Markus, edited by William E. Klingshirn and Mark Vessey, 97–114. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Griffith, Sidney H. “The Marks of the ‘True Church’ According to Ephraem’s Hymns against Heresies.” In After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Hans J. W. Drijvers, edited by Gerrit J. Reinink and Alexander C. Klugkist, 125–140. Leuven: Peeters, 1999. .

- Griffith, Sidney H. Faith Adoring the Mystery: Reading the Bible with St. Ephraem the Syrian. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1997.

- Guillaumont, A. “Genèse 1,1–2 selon les commentateurs syriaques.” In IN PRINCIPIO: Interpretations des premiers versets de la Genèse, Études augustiniennes 152 (Paris, 1973): 115–132. .

- Hall, Stuart G., tr., “The Second Book against Eunomius (Translation).” In Gregory of Nyssa, Contra Eunomium II: An English Version with Supporting Studies: Proceedings of the 10th International Colloquium on Gregory of Nyssa (Olomouc, September 15–18, 2004), edited by Lenka Karfíková, Scot Douglass, Johannes Zachhuber, and Stuart George Hall, 59–201. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Hartung, Blake. “The Authorship and Dating of the Syriac Corpus Attributed to Ephrem of Nisibis: A Reassessment,” Zeitschrift für antikes Christentum 22:2 (2018): 296-321. .

- Harvey, Susan Ashbrook. “Spoken Words, Voiced Silence: Biblical Women in Syriac Tradition.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 9:1 (2001): 105–131. .

- Heal, Kristian. “Reworking the Biblical Text in the Dramatic Dialogue Poems on the Old Testament Patriarch Joseph.” In The Peshiṭta: Its Use in Literature and Liturgy: Papers Read at the Third Peshiṭta Symposium , edited by Bas ter Haar Romeny, 87–98. Leiden: Brill, 2006. .

- Hespel, Robert and René Draguet, eds. Théodore bar Koni: Livre des scolies: recension de Séert, CSCO 431–432, SS 187–188. Leuven: Peeters, 1981–1982.

- Hidal, Sten. Interpretatio Syriaca: Die Kommentare des heilegen Ephräm des Syrers zu Genesis und Exodus mit besondere Berücksichtigung ihrer auslegungsgeschichten Stellung. Lund: Gkeerup, 1974. .

- Hilhorst, Ton. “The Prestige of Hebrew in the Christian World of Late Antiquity and Middle Ages.” In Flores Florentino: Dead Sea Scrolls and Other Early Jewish Studies in Honour of Florentino García Martínez, edited by Anthony Hilhorst, Émile Puech, and Eibert Tigchelaar, 777–802. Leiden: Brill, 2007. .

- Hovhanessian, Vahan. “The Commentaries on the Letters of Paul Attributed to Ephrem the Syrian in Armenian Manuscripts.” The Harp: A Review of Syriac and Oriental Studies 24 (2009): 311–27. .

- Jaeger W., ed. Gregorii Nysseni opera , vol. 1: Contra Eunomium libros I–II continens. Leiden: Brill, 1960. .

- Jansma, T. “Ephraems Beschreibung des ersten Tages der Schöpfung.” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 37 (1971): 295–316. .

- de Jonge, M. Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs: A Critical Edition of the Greek Text . Pseudepigrapha Veteris Testamenti Graece 1.2. Leiden: Brill, 1978. .

- Joosten, Jan. “West Aramaic Elements in the Old Syriac and Peshitta Gospels.” Journal of Biblical Literature 110:2 (1991): 271–289. .

- Klijn, A. F. J. “A Note on Ephrem’s Commentary on the Pauline Epistles.” Journal of Theological Studies 5.1 (1954): 76–78.

- Kremer, Thomas. Mundus Primus: Die Geschichte der Welt und des Menschen von Adam bis Noach im Genesiskommentar Ephräms des Syrers. Leuven: Peeters, 2012.

- Kronholm, Tryggve. Motifs from Genesis 1–11 in the Genuine Hymns of Ephrem the Syrian, with Particular Reference to the Influence of Jewish Exegetical Traditions. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1978. .

- Leonhard, Clemens. “Die Beschneidung Christi in der syrischen Schatzhöhle . Beobachtungen zu Datierung und Überlieferung des Werks.” In Syriaca II. Beiträge zum 3. deutschen Syrologen-Symposium in Vierzehnheiligen 2002 , edited by M. Tamcke, 11–28. Münster: Studien zur orientalischen Kirchengeschichte Bd. 33, 2004. .

- Leonhard, Clemens. “Observations on the Date of the Syriac Cave of Treasures .” In The World of the Aramaeans , edited by P. M. M. Daviau et al., 3:255–93. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. .

- Lund, J. A. “Observations on Some Biblical Citations in Ephrem’s Commentary on Genesis.” Aramaic Studies 4 (2006): 207–220. .

- Macomber, William F., ed. Six Explanations of the Liturgical Feasts by Cyrus of Edessa, an East Syrian Theologian of the Mid-Sixth Century , CSCO 355–356, SS 155–156. Leuven: CorpusSCO, 1974. .

- Mathews, Edward G. and Joseph P. Amar, trans., Kathleen E. McVey, ed. St. Ephrem the Syrian. Selected Prose Works. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1994. .

- Marcovich, M. Origenes: Contra Celsum libri VIII. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 54. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- McVey, Kathleen E. Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns. New York: Paulist Press, 1989.

- Meredith, Anthony. “The Language of God and Human Language ( CE II 195–293).” In Gregory of Nyssa, Contra Eunomium II: An English Version with Supporting Studies: Proceedings of the 10th International Colloquium on Gregory of Nyssa (Olomouc, September 15–18, 2004), edited by Lenka Karfíková, Scot Douglass, Johannes Zachhuber, and Stuart George Hall, 247–256. Leiden: Brill, 2007. .

- Migne, J.-P., ed. Cyril of Alexandria: Glaphyra in Pentateuchum 2, PG 69. .

- Migne, J.-P., ed. Gregory Nazianzen: Orationes , PG 36. .

- Migne, J.-P., ed. Jerome: Commentarii in epistulas Paulinas, PL 26. .

- Minets, Yuliya. “The Tower of Babel and Language Corruption: Approaching Linguistic Disasters in Late Antiquity.” Studies in Late Antiquity (forthcoming 2022). .

- Minets, Yuliya. The Slow Fall of Babel: Languages and Identities in Late Antique Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. .

- Minov, Sergey. “Date and Provenance of the Syriac Cave of Treasures : A Reappraisal.” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 20.1 (2017): 129–229. .

- Minov, Sergey. Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran . Jerusalem Studies in Religion and Culture 26. Leiden: Brill, 2021. .

- Monnickendam, Yifat. “How Greek is Ephrem’s Syriac?: Ephrem’s Commentary Genesis as a Case Study.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 23.2 (2015): 213-244. .

- Moss, Yonatan. “The Language of Paradise: Hebrew or Syriac? Linguistic Speculations and Linguistic Realities in Late Antiquity.” In Paradise in Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Views, edited by Markus Bockmuehl and Guy G. Stroumsa, 120-137. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Mras, K., ed. Eusebius Werke , vol. 8: Die Praeparatio evangelica , GCS 43.1 and 43.2. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1954–1956. .

- Muto, S. “Early Syriac Hermeneutics.” The Harp 11–12 (1998): 45–65. .

- Narinskaya, Elena. Ephrem, a ‘Jewish’ Sage: A Comparison of the Exegetical Writings of St. Ephrem the Syrian and Jewish Traditions. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2010. .

- Niehoff, Maren R. “What is in a Name? Philo’s Mystical Philosophy of Language.” Jewish Studies Quarterly 2 (1995): 220–52. .

- Pereira, A. S. Rodrigues. “Two Syriac Verse Homilies on Joseph.” Jaarbericht. Ex Oriente Lux 31 (1989/1990): 95–120. .

- Petruccione, John F. and Robert C. Hill, eds. Theodoret of Cyrrhus: The Questions on the Octateuch, 2 vols. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 2007.

- Possekel, Ute. Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts on the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian. Leuven: Peeters, 1999. .

- Pusey, P. E., ed. Sancti patris nostri Cyrilli archiepiscopi Alexandrini Opera, vol 3 : In D. Joannis Evangelium. Fragmenta in sancti Pauli epistulam I ad Corinthios. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1872. .

- Reischl, W. C., and J. Rupp, eds. Cyrilli Hierosolymorum archiepiscopi opera quae supersunt omnia, 2 vols. Munich: Lentner, 1848–1860. .

- Resnick, Irvin M. “ Lingua Dei, Lingua Hominis : Sacred Language and Medieval Texts.” Viator 21 (1990): 51-74. .

- Ri, Su-Min, ed. La caverne des trésors: Les deux recensions syriaques, CSCO 486–487, SS 207–208. Leuven: Peeters, 1987.

- Robertson, David. Word and Meaning in Ancient Alexandria: Theories of Language from Philo to Plotinus. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008. .

- Romeny, Bas ter Haar. A Syrian in Greek Dress: The Use of Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac Biblical Texts in Eusebius of Emesa’s Commentary on Genesis. Leuven: Peeters, 1997. .

- Rompay, Lucas Van, ed. Le Commentaire sur Genèse–Exode 9,32 du manuscrit (olim) Diyarbakır 22, 2 vols., CSCO 483–484, SS 205–206. Leuven: Peeters, 1986.

- Rompay, Lucas Van. “Antiochene Biblical Interpretation: Greek and Syriac.” In Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation: A Collection of Essays, edited by. J. Frishman and L. Van Rompay, 103–112. Leuven: Peeters, 1997. .

- Rompay, Lucas van. “The Christian Syriac Tradition of Interpretation.” In Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: The History of its Interpretation , edited by Magne Sæbø, 1:612–641. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996. .

- Rooy, Raf van. “Πόθεν οὖν ἡ τοσαύτη διαφωνία? Greek Patristic Authors Discussing Linguistic Origin, Diversity, Change and Kinship.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 23.1 (2013): 21–54.

- Ruani, Flavia. Éphrem de Nisibe: Hymnes contre les hérésies . Bibliothèque de l’Orient chrétien 4. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2018. .

- Rubin, Milka. “The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language: A Case of Cultural Polemics in Antiquity.” Journal of Jewish Studies 49 (1998): 306–33. .

- Runia, David T. “Etymology as an Allegorical Technique in Philo of Alexandria.” The Studia Philonica Annual 16 (2004): 101–21. .

- Ruzer, Serge. “The Cave of Treasures on Swearing by Abel’s Blood and Expulsion from Paradise: Two Exegetical Motifs in Context.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 9.2 (2001): 251-271. .

- S. Ephræm Syri commentarii in epistolas D. Pauli nunc primum ex Armenio in Latinum sermonem a patribus Mekitharistis translate. Venice: Typographia Sancti Lazari, 1893.

- Sabatier, P., E. Beuron, and R. Gryson, eds. Vetus Latina: Die Reste der altlateinischen Bibel. Freiburg: Herder, 1949.

- Schwartz, Seth. “Language, Power and Identity in Ancient Palestine.” Past and Present 148 (1995): 3–47. .

- Sedley, David. Plato’s Cratylus . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. .

- Stern, Menahem, ed. Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism, vol. 2 . Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1974–1980. .

- The Old Testament in Syriac, According to the Peshiṭta Version, 18 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1966–2019. .

- Tonneau, R.-R., ed. Ephrem: In Genesim et in Exodum commentarii, CSCO 152–153, SS 71–72. Leuven: L. Durbecq, 1955.

- Uehlinger, Christoph. Weltreich und “eine Rede”: eine neue Deutung der sogenannten Turmbauerzählung (Gen 11, 1–9) . Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1990. .

- Vaggione, R. P., ed. Eunomius : The Extant Works . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. .

- Wallis Budge, E. A. tr. The Book of the Cave of Treasures: A History of the Patriarchs and the Kings, their Successors, from the Creation to the Crucifixion of Christ. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1927.

- Walters, J. Edward, ed. Ephrem the Syrian’s Hymns on the Unleavened Bread. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2011. .

- Wevers, John William, ed. Vetus Testamentum Graecum, Auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1974. .

- Wickes, Jeffrey. Bible and Poetry in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Ephrem’s Hymns on Faith. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. .

- Wickes, Jeffrey. “Ephrem’s Interpretation of Genesis.” St Vladimirs Theological Quarterly 52.1 (2008): 45–65. .

- Wickes, Jeffrey. Ephrem: Hymns on Faith . Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2015. .

- Winslow, Karen S. “The Exegesis of Exodus by Ephrem the Syrian.” In Exegesis and Hermeneutics in the Churches of the East: Select Papers from the SBL Meeting in San Diego, 2007, edited by Vahan S. Hovhanessian, 33–42. New York: Peter Lang, 2009.

- Winston, David. “Aspects of Philo’s Linguistic Theory.” The Studia Philonica Annual 3 (1991): 109–125. .

- Wood, Philip. “Syrian Identity in the Cave of Treasures.” The Harp 22 (2007): 131–140. .

- Zingerle, Antonius, ed. Hilarii episcopi Pictaviensis Tractatus super Psalmos, CSEL 22. Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1891. .

Footnotes

1 The Cave of Treasures 24.9–11 (Su-Min Ri, CSCO 486, SS 207:186–9); tr. after: The Book of the Cave of Treasures: A History of the Patriarchs and the Kings, their Successors, from the Creation to the Crucifixion of Christ, trans. E. A. Wallis Budge (London: The Religious Tract Society, 1927), 132.

2 Sergey Minov, Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran, Jerusalem Studies in Religion and Culture 26 (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 36-40; Sergey Minov, “Date and Provenance of the Syriac Cave of Treasures: A Reappraisal,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 20.1 (2017), 129-229. See also: Clemens Leonhard, “Observations on the Date of the Syriac Cave of Treasures,” in The World of the Aramaeans, ed. P. M. M. Daviau et al. (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 3:255–93; Clemens Leonhard, “Die Beschneidung Christi in der syrischen Schatzhöhle. Beobachtungen zu Datierung und Überlieferung des Werks,” in Syriaca II. Beiträge zum 3. deutschen Syrologen-Symposium in Vierzehnheiligen 2002, ed. M. Tamcke (Münster: Studien zur orientalischen Kirchengeschichte Bd. 33, 2004), 11–28; Philip Wood, “Syrian Identity in the Cave of Treasures,” The Harp 22 (2007), 131–140.

3 See, for example, the discussion: Serge Ruzer, “The Cave of Treasures on Swearing by Abel’s Blood and Expulsion from Paradise: Two Exegetical Motifs in Context,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 9.2 (2001), 251-271.

4 Among the Syrian Orthodox, the views are attested in: On Paradise by Moses bar Kepha, ninth century (Moses bar Kepha, On Paradise (Bein. Syr. 10, 61b–62a), cited in Yonatan Moss, “The Language of Paradise: Hebrew or Syriac? Linguistic Speculations and Linguistic Realities in Late Antiquity,” in Paradise in Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Views, ed. Markus Bockmuehl and Guy G. Stroumsa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 128–129); among the writers representing the Church of the East – in the Book of Scholia by Theodore bar Koni, eighth century (Theodore bar Koni, Livre des scolies: recension de Séert 2.112-114 (Robert Hespel, and René Draguet, CSCO 431, SS 187:125–128)), the anonymous Diyarbakır commentary, eighth century (Commentary on Genesis-Exodus (Diyarbakir 22 Manuscript) 11.7 (Van Rompay, CSCO 483, SS 205:68–9)), and the Commentary on Genesis by Ishoʿdad of Merv, c.850 (Ishoʿdad of Merv, Commentaries on the Old Testament (van den Eynde, CSCO 126, SS 67:135)).

5 Minov, Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures, 194.

6 The Book of the Cave of Treasures, trans. E. A. Wallis Budge, xi.

7 The Book of the Cave of Treasures, trans. E. A. Wallis Budge, 22.

8 See, for example, Marilyn F. Collins, “The Hidden Vessels in Samaritan Traditions,” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 3.2 (1972), 107.

9 Su-Min Ri, ed. and trans. La Caverne des trésors: Les deux recensions syriaques, CSCO 487, SS 208 (Leuven: Peeters, 1987), xiv–xviii.

10 Josef Eskhult, “The Primeval Language and Hebrew Ethnicity in Ancient Jewish and Christian Thought until Augustine,” Revue des etudes augustiniennes 60 (2014), 326–27, 341.

11 Ephrem, Commentary on Genesis 8.3 (R.-R. Tonneau, CSCO 152, SS 71:66); trans.: St. Ephrem the Syrian, Selected Prose Works, trans. Edward G. Mathews and Joseph P. Amar, ed. Kathleen E. McVey (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1994), 148.

12 Milka Rubin, “The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language: A Case of Cultural Polemics in Antiquity,” Journal of Jewish Studies 49 (1998), 322.

13 Rubin, “The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language,” 323. This is most likely a secondary tradition that developed after the Cave of Treasures and was based on this text; it does not convey authentic testimony that predates this work.

14 Minov, Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures, 275.

15 Minov, Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures, 276.

16 On linguistic thought in the Syriac tradition: Riccardo Contini, “Aspects of Linguistic Thought in the Syriac Exegetical Tradition,” in Syriac Encounters: Papers from the Sixth North American Syriac Symposium, ed. M. Doerfler, E. Fiano, and K. Smith (Leuven: Peeters, 2015), 91–117.

17 Ephrem, Against Heresies 5.6 (Edmund Beck, CSCO 169, SS 76:19).

18 Jacob of Sarug: Homily on the Tower of Babel, ed. and tr. Aaron Butts (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010).

19 Ephrem, Sermons on Faith 6.139-140 and 157-158 (Edmund Beck, CSCO 212, SS 88:44–45).

20 Minov, Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures, 255–59.

21 Edmund Beck, ed. and trans., Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones de fide, CSCO 213, SS 89 (Leuven: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1961), 63, note 18. This secondary meaning of the ethnonym “Arameans” referring to “heathern” or “non-Jew” was possibly derived from the West Aramaic, probably Jewish, linguistic tradition; see Jan Joosten, “West Aramaic Elements in the Old Syriac and Peshitta Gospels,” Journal of Biblical Literature 110:2 (1991), 279–280.

22 Ephrem, Against Heresies 23.5 (Edmund Beck, CSCO 169, SS 76:87–88).

23 For the Septuagint, Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion versions of the Old Testament, the following edition was used: John William Wevers, ed., Vetus Testamentum Graecum, Auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1974).

24 For the Vetus Latina versions, see: P. Sabatier, E. Beuron, and R. Gryson, eds., Vetus Latina: Die Reste der altlateinischen Bibel (Freiburg: Herder, 1949).

25 For the Vulgate, see: B. Fischer, R. Weber, and R. Gryson, eds., Biblia sacra: Iuxta Vulgatam versionem (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1994).

26 References to the Abraham eponymy in the works of some non-Jewish Hellenistic historians, such as Alexander Polyhistor of Miletus (first century BCE) and Claudius Charax of Pergamon (second century CE), can be explained by their access to sources informed about the Hebrew reading of Genesis 14:13. Alexander Polyhistor referred to a certain Artapanus, who was probably a Jewish Hellenistic historian living in Alexandria in the late third or second century BCE. Alexander himself was in turn quoted by Eusebius of Caesarea, Preparation for the Gospel 9.18.1 (K. Mras, Eusebius Werke 8, GCS 43). Claudius Charax, as quoted by Stephanus of Byzantium, did not indicate his source, see Menahem Stern, ed., Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1974–1980), 2:161.

27 Eskhult, “The Primeval Language,” 306–9. See also: Gilles Dorival, “Le patriarche Héber et la tour de Babel: Un apocryphe disparu?” in Poussières de christianisme et de judaïsme antiques: Études réunies en l’honneur de Jean-Daniel Kaestli et Éric Junod, ed. A. Frey, R. Gounelle (Lausanne: Éditions du Zèbre, 2007), 181–201.

28 T. Jansma, M. D. Koester, The Old Testament in Syriac, According to the Peshiṭta Version, Part I, fasc. 1: Preface; Genesis–Exodus (Leiden: Brill, 1977), 24.

29 For Ephrem’s familiarity with Jewish exegetical traditions, see: Sebastian P. Brock, “Jewish Traditions in Syriac Sources,” Journal of Jewish Studies 30 (1979), 212-32; Elena Narinskaya, Ephrem, a ‘Jewish’ Sage: A Comparison of the Exegetical Writings of St. Ephrem the Syrian and Jewish Traditions (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2010); Karen S. Winslow, “The Exegesis of Exodus by Ephrem the Syrian,” in Exegesis and Hermeneutics in the Churches of the East: Select Papers from the SBL Meeting in San Diego, 2007, ed. Vahan S. Hovhanessian (New York: Peter Lang, 2009), 33–42; Nabil el-Khoury, “Hermeneutics in the Works of Ephraim the Syrian,” in IV Symposium Syriacum, 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature (Groningen-Oosterhesselen 10-12 September), ed. H. J. W Drijvers, R. Levanant S. J., C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink (Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987), 93-99; Tryggve Kronholm, Motifs from Genesis 1–11 in the Genuine Hymns of Ephrem the Syrian, with Particular Reference to the Influence of Jewish Exegetical Traditions (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1978); Paul Féghali, “Influence des Targums sur la pensée exégétique d’Ephrem?” in IV Symposium Syriacum, 1984: Literary Genres in Syriac Literature (Groningen-Oosterhesselen 10-12 September), ed. H. J. W Drijvers, R. Levanant S. J., C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink (Roma: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1987), 71-82; Yifat Monnickendam, “How Greek is Ephrem’s Syriac?: Ephrem’s Commentary Genesis as a Case Study,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 23.2 (2015): 213-244.

30 Among early Christian writers, Theophilus of Antioch, Hippolytus of Rome, John Chrysostom, Jerome, Augustine, Cassiodorus, Isidore of Seville, and many others asserted that the Hebrews were named after Heber. Julius Africanus emphatically rejected this opinion, while Eusebius of Caesarea entertained both possible etymologies of the word “Hebrew” – from Heber and from Abraham ha-ʿibri, and though he might have preferred the latter, he never made a decisive choice between the two; see Yuliya Minets, The Slow Fall of Babel: Languages and Identities in Late Antique Christianity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 122-137.

31 Rubin, “The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language,” 309–14; E. Eshel and M. E. Stone, “The Holy Language at the End of the Days in Light of a New Fragment Found at Qumran,” Tarbiz 62 (1992–1993), 169–78; Seth Schwartz, “Language, Power and Identity in Ancient Palestine,” Past and Present 148 (1995): 3–47 at 12–31.

32 Anthony Meredith, “The Language of God and Human Language (CE II 195–293),” in Gregory of Nyssa, Contra Eunomium II: An English Version with Supporting Studies: Proceedings of the 10th International Colloquium on Gregory of Nyssa (Olomouc, September 15–18, 2004), ed. Lenka Karfíková, Scot Douglass, Johannes Zachhuber, and Stuart George Hall (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 247–56, at 250–1; Eskhult, “The Primeval Language,” 341; Irvin M. Resnick, “Lingua Dei, Lingua Hominis: Sacred Language and Medieval Texts,” Viator 21 (1990), 51-74 at 57–58.