Arabic nuṭfah and Syriac nuṭptā in Avicenna’s and Barhebraeus’s Works

Substantial Change, Embryology, and Ensoulment

This article analyzes how the Syriac word for ‘drop,’ nuṭptā, was used by Barhebraeus (1226–1286) with the meaning of ‘drop of semen’ or ‘sperm drop.’ The term appears in Barhebraeus’s writings within broader exami-nations of substantial change, embryology, and ensoulment. I argue that Barhebraeus received the term in this sense from Avicenna (ca. 980–1037), including the latter’s concept of substantial change. While Barhebraeus’s reception of Avicenna’s philosophy has implications for his position regarding the time of ensoulment of the unborn, the independence of Barhebraeus’s embryology will also become apparent. The paper thus contributes to research on notions of the unborn in both Arabic and especially Syriac literature and the investigation of Barhebraeus’s creative appropriation of Avicennan philosophy. These two aspects are connected by analyzing the critical term nuṭptā/nuṭfah.

Bar ʿEḇrāyā (1226–1286), also known as Barhebraeus, is a significant representative of the so-called Syriac Renaissance (ca. 1100–1300), in which new intellectual developments by Muslim authors and thinkers were integrated into the Syriac learned and literary tradition.1 In Barhebraeus’s reception of Islamic Vorlagen and ideas, Ibn Sīnā (ca. 980–1037), also known as Avicenna, looms large.2 As an example of this reception, I will analyze here how the Syriac word for ‘drop,’ nuṭptā, was used by Barhebraeus with the meaning of ‘drop of semen’ or ‘sperm drop.’ The term appears in Barhebraeus’s writings within broader examinations of substantial change, embryology, and ensoulment. I will argue that Barhebraeus received the term in this sense from Avicenna, including the latter’s concept of substantial change. While Barhebraeus’s reception of Avicenna’s philosophy has implications for his position regarding the time of ensoulment of the unborn, the independence of Barhebraeus’s embryology will also become clear. The paper thus contributes to research on notions of the unborn in both Arabic and especially Syriac literature as well as the investigation of Barhebraeus’s creative appropriation of Avicennan philosophy. These two aspects are connected by analyzing the key term nuṭptā/nuṭfah.

The first part of this paper will examine key passages from Barhebraeus’s works that highlight the major contours of his thoughts in connection with the Syriac term nuṭptā. This discussion will provide a foundation for the second part, in which I will investigate the correspondence of these passages to sections in Avicenna’s writings, including key differences between the authors. In the third and last step, I will trace the development of the term nuṭptā beginning with pre-Islamic Syriac literature. As a whole, I will argue that Barhebraeus adapted the Arabic term nuṭfah and the underlying philosophical concepts and integrated this into his synthesis of embryological ideas.

Barhebraeus’s conceptions of substantial change, embryology, and ensoulment

I will first investigate four key passages that demonstrate how Barhebraeus uses nuṭptā in his writings. Moving forward, it will become clear that the term nuṭptā is directly linked to Barhebraeus’s conceptions of substantial change, embryology, and ensoulment. As a starting point, one can look at the shortest of Barhebraeus’s three philosophical compendia, the Discourse of Wisdom. In this work, the term nuṭptā for ‘sperm drop’ surfaces in the context of a discussion of ‘coming-to-be’ and ‘passing-away’, a central theme of natural philosophy following Aristotle:

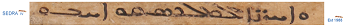

“[1] When we say that the drop (nuṭptā) becomes human, we do not mean that the drop remains what it is nor that it vanishes in its entirety. Rather, the nature (kyānā) of the drop passes away from it and it clothes itself with human nature.3”

Barhebraeus illustrates here the Aristotelian notion of matter and form: if a being ceases to be, another being originates from the same matter but with a different form.4 According to the categories that Aristotle introduces (such as substance, quality, quantity, or place), the change involved in this process pertains to the category of substance.5 As Barhebraeus puts it, the drop does not remain what it is. Change in other categories, on the other hand, as in quality or quantity, does not alter the substance or being itself. A human can become sick or healthy, bigger or smaller, while remaining human.

There is a fundamental difference between substantial change and other kinds of change. A being can change continuously in quality or quantity. For example, a tree grows continuously, and a stone becomes hot or cold progressively.6 However, can a human being become more or less human? Can the sperm drop become a human being little by little? Barhebraeus addresses this topic in a section known as the Book of Categories in his longer philosophical summa, the Cream of Wisdom:

“[2] Change in the category of substance does not come about through change which comes to be [or] passes away continuously (b-[ʾ]idā b-[ʾ]idā) but suddenly (menšel[y]). Such is the change of the body in respect to reproduction: not a change of substance, but an alteration in the quality of the seed (zarʿā) until the aptitude towards the reception [of the new form] is perfected. Then, the form of the animate being (ṣurat ḥayyutā) is bestowed suddenly by the Giver of Forms.7”

Barhebraeus states that change or movement in the Aristotelian category of substance happens suddenly (menšel[y]). Here, the less ambiguous term zarʿā is used for human semen. The changes happening to the semen until it becomes an animate being are attributed to the category of ‘quality.’ In his Book of the Pupils of the Eye, a writing on logic, there is a parallel passage:

“[3] To say that coming-to-be and passing-away of substance are movements is not correct, in that movement occurs by degrees and continuously, while coming-to-be and passing-away are sudden. Therefore, the drop (nuṭpṯā) changes in quality and quantity in the womb until all at once the form of humanity dawns upon it. For this reason, it is not said that this one [i.e. an unborn child] is more human due to the fact that he has changed more towards humanity, and that this [other] one [i.e. another unborn] is less [human] because he has changed less towards it.8”

Here, as in text [1], the human seed is termed nuṭptā, and the changes it undergoes until it becomes a human being are attributed to the categories of both quality and quantity. The end of this passage clearly expresses the notion that the unborn can either be human or non-human – and nothing in between. Presumably, what Barhebraeus implies with ‘more human’ and ‘less human’ is the progress of embryological development.

Ultimately, Barhebraeus’s notion of substantial change as taking place suddenly has implications for his position regarding ensoulment as presented in his theological writings. He wrote two theological compendia: the extensive Candelabrum of the Sanctuary and a shorter reworking of the Candelabrum known as the Book of Rays.9 In the Candelabrum, Barhebraeus opposes the view that the human body precedes its soul and rejects the idea that ensoulment occurs later during pregnancy.10 In the later Book of Rays, however, Barhebraeus writes:

“[4] Regarding the simultaneity of the origination (šāwyut šwiḥutā) of soul and body: It is rightly assumed for the time of the perfection of the body (šumlāy pagrā), but not for the time of the establishment (tarmitā) of the sperm drop (nuṭptā).11”

Comparing this passage with texts [1]–[3] above, the implicit idea is that the human seed cannot be substantially identical to the human being, and the substantial change from ‘drop’ to a human being cannot happen continuously. In Barhebraeus’s view, the reception of the human soul – understood as the human form – occurs when the body has been completed.12

In the Book of Rays, following text [4], Barhebraeus interprets Leviticus 12:2–5 as a biblical proof-text for his position. In Leviticus, the number of days determined for a mother’s purification after birth is 40 for a boy and 80 for a girl.13 He explains that this is equal to the number of days the mother has carried an inanimate, dead body. In the Candelabrum, the same argument is attributed by Barhebraeus explicitly to Philoxenos of Mabbug (before 440–523) – and rejected.14 We will return to these periods of embryological development later.

Avicenna’s notion of substantial change as Barhebraeus’s point of reference

In the following, I will explore Avicenna as Barhebraeus’s point of reference for texts [1]–[4] discussed above. What links the textual passages by both authors is the illustration of the philosophical problem of substantial change with human procreation. At the same time, differences in their notion of embryological development will become apparent. We can identify Barhebraeus’s reception of Avicenna as creative appropriation rather than mere adoption.

Avicenna’s understanding of substantial change was first discussed in 2004 in an article by Jon McGinnis.15 According to McGinnis, Avicenna offered a novel explanation of the problem of substantial change as taking place suddenly.16 In the general treatment of physics in his Book of the Healing, Avicenna illustrates the problem using human generation:

“[5] Until the semen (manīy) becomes an animate being (ḥayawān), other acts of coming-to-be happen to it, which introduce changes in quality and quantity between the two [i.e. the semen and the animate being]. The semen, then, changes continuously little by little (lā yazāl yastaḥīl yasīran yasīran) – while still being semen – until it comes to the brink of being stripped of its seminal form and becomes an ʿalaqah. And such is its state until it comes to be a muḍġah.17 After that bones, nerves/sinews, blood vessels and other things we do not grasp [come to be], and thus until it receives the form of the animate being.18”

We know that Barhebraeus extensively used Avicenna’s Book of the Healing for the Cream of Wisdom and his other works.19 In this case, too, there are several points in which the quotations from Barhebraeus’s works given above overlap with what Avicenna states in text [5]. One general agreement between the texts cited is to use human generation as a prime example of the underlying issue of substantial change. Regarding terminology, in text [5], Avicenna uses the Arabic word manīy, ‘the ejaculate,’ which is often used in a more technical sense than the figurative term nuṭfah, ‘(sperm) drop.’ Barhebraeus accordingly uses the Syriac word zarʿā, ‘seed’ in text [2].20 I will later point out other instances where Avicenna uses nuṭfah that correspond to Barhebraeus’s usage of nuṭptā. Moreover, the changes happening to the semen are described in the quotations by the two authors as both qualitative and quantitative. Only when matter undergoes these continuous changes in the categories of quality and quantity and is thus prepared or suitable does it receive a new form. Avicenna adds:

“[6] However, the outer appearance of the situation suggests that this is a single process from one substantial form to another substantial form and makes one believe therefore that there is motion [i.e. change] (ḥarakah) in the [category of] substance, when this is not the case. Rather, there are many motions and rests.21”

Although the term ‘sudden’ does not appear here, Avicenna’s underlying notion of substantial change becomes apparent. He conceives the motion or change (ḥarakah) in the category of substance as sudden and there is no substantial change in between, i.e. the process of substantial change comes to a rest. This marks yet another point of intersection between Avicenna and Barhebraeus, and the final one explored here.

However, there is also an essential difference between the two authors’ accounts. Avicenna mentions further embryological stages apart from the semen, namely ʿalaqah and muḍġah, as well as bones, nerves, and blood vessels. Most of these terms are found in the Quran and later Islamic religious texts such as Hadith.22 Barhebraeus, on the other hand, only refers to a seed (zarʿā) or a drop (nuṭptā), which eventually becomes a human being (or an animate being more generally).

This difference in embryological terminology between the passages cited is not an isolated case. For comparison, one can consider Barhebraeus’s description of procreation and embryological development in the zoological part of the Cream of Wisdom. As is the case elsewhere, his primary point of reference is Avicenna’s Book of the Healing, juxtaposed in many smaller or greater details with Aristotle’s History of Animals (Historia animalium).23 Barhebraeus often literally translates Avicenna’s Book of the Healing into Syriac, and thus, the differences between the two works here stand out. In his account, Barhebraeus skips a rather long passage by Avicenna treating the embryological stages, including those with Islamic connotations.24 Barhebraeus only takes up a few aspects of Avicenna’s work in his section on the development of the “main organs from the two seeds.”25 One major difference is that Barhebraeus does not provide a terminological or conceptual match for muḍġah. Further, Barhebraeus only refers to the similarity of the embryo’s body to an ʿellaqtā26 – Barhebraeus’s Syriac equivalent to Arabic ʿalaqah – whereas Avicenna states that the drop becomes an ʿalaqah.

Differences between Barhebraeus’s and Avicenna’s accounts demonstrate the independence of Barhebraeus’s embryological synthesis. This indipendent thought includes his idea of later ensoulment in the Book of Rays and of the duration of the embryo’s formation. Concerning the latter, Barhebraeus’s presentation of the duration of the embryo’s formation in the zoology of the Cream of Wisdom is taken from the Aristotelian account in the History of Animals, namely, 40 days for a male child and three months for a female child.27 Avicenna, on the other hand, states that the formation of the embryo takes roughly 40 days. A girl might develop more slowly, but there is always some natural variation between individuals.28 Moreover, the periods provided by Barhebraeus also echo those for ensoulment in the Book of Rays (cf. text [4] above). While we have seen in texts [2] and [3] that Avicenna’s concept of substantial change constitutes an essential aspect of Barhebraeus’s notion of the unborn, the differences identified here between their accounts show that Barhebraeus developed his own distinct notion of the unborn. It can be described as a synthesis of Aristotelian, Avicennan, and Syriac-Christian notions of the unborn.29

Nuṭptā/nuṭfah in Syriac and Arabic texts before Barhebraeus

In what remains, I will trace the term nuṭptā/nuṭfah as ‘sperm drop’ more broadly, arguing that Barhebraeus adapts it from philosophical contexts in Avicenna’s (and possibly in other Arabic-Islamic) writings. To begin with, I have not found any instances where nuṭptā is metaphorically used for semen in earlier Syriac literature.30 In the medieval Syriac-Arabic dictionary of Bar Bahlul (fl. ca. 1050), the meaning of ‘semen’ is only attested for nuṭptā in a single manuscript from 1796; it is most likely a later addition.31 There is no attestation of nuṭptā as semen in the Book of the Translator by Eliya of Nisibis (975–1046).32 Searching in the digital thesaurus Simtho, one can mention passages where Ephrem the Syrian (d. 373) or Babai the Great (ca. 551–628) treat the biblical account of the creation of humankind from a grain of dust and drop (nuṭptā) of water.33 Another passage (not found via Simtho) is in the Cave of Treasures.34 Moreover, in the Hexaemera of Jacob of Serugh (ca. 451–521) and Jacob of Edessa (ca. 630–708), human procreation is treated alongside and, in the case of Jacob of Serugh, as partially analogous to God’s creation of the first humans. However, the male semen is termed zarʿā in these cases.35 In short, Barhebraeus does not seem to have inherited this term from earlier Syriac writings.36

In the Quran, one finds the sequence nuṭfah, ʿalaqah and muḍġah as well as nuṭfah on its own.37 This Quranic material and certain Hadith and early legal texts developed into an Islamic embryology, which was and is still widely received.38 In addition, the term nuṭfah for semen is found in two relatively early texts: the Arabic translation of Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals (De generatione animalium) as well as in the Book of the Secret of Creation attributed to Apollonios of Tyana (ca. 40–120). These texts should be contextualized in reference to other works of natural philosophy or alchemy in the case of the Secret of Creation. With their origins in the learned Greek tradition, their translation or redaction took place within a Christian milieu. However, no direct Syriac intermediary texts are known or extant.39 In the Secret of Creation, nuṭfah is used, among other things, for plant seeds and even offshoots.40 Most notably, the Book of Secrets mentions nuṭfah in cosmogony, along the lines of logoi spermatikoi.41 In the translation of Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals, nuṭfah is used in a short passage for various Greek terms, even for the egg yolk.42 Accordingly, in both of these works, nuṭfah renders different phenomena of procreation into Arabic. Recalling the probable Syriac-Christian background of the translators or redactors, it could be inferred that there had been no fixed terminology in Syriac for nuṭptā as male semen or sperm drop.43

In his writings in the 10th/11th century, Avicenna used these Islamic terms and notions of the unborn.44 In the following, I will highlight how he draws on semen and, more generally, on human procreation to illustrate philosophical problems. Only in the case of biological problems proper does Avicenna refer to manīy, ‘the ejaculate,’ whereas nuṭfah is used in most other cases. For example, in the Book on Demonstrative Proof within his Book of the Healing, he writes:

“[7] We explain this in respect to something very obvious (aẓhar), such as the human being: His effective, obvious cause is either the human being [itself], the drop (nuṭfah) or the power [of formation] in the drop and the [potential] form therein.45”

Here, Avicenna discusses causation theory and how this relates to proper logical proofs and natural processes.46 Leaving the philosophical details aside, I want to point out that this kind of illustration is widespread and is presented as very obvious (aẓhar) by Avicenna. Against this background, further such instances in his writings can be examined. In a passage of the Physics in the Book of the Healing, Avicenna exemplifies how the active, formal, and final causes are one and the same in the case of human generation:

“[8] Indeed, in the father there is the principle for the generation of the human form from the drop. But not all of this is from the father, rather the human form [alone]. And that which results in regard to the drop (al-ḥāṣil fī n-nuṭfah) is nothing other than the human form. And the end to which the drop moves/changes (tataḥarrak) is nothing other than the human form.47”

Certainly, passages where Avicenna treats causal theory in connection with human generation deserve more study.48 A clearer example can be found in the Doctrines of the Philosophers of al-Ġazālī (1055–1111), a post-Avicennan author whose works Barhebraeus also adapted.49 When treating the question of whether the soul precedes the body, al-Ġazālī describes the drop of semen as an instrument (ālah) for the soul in the human coming-to-be.50

The preceding examples show how human procreation is used in Islamic philosophy, specifically by Avicenna, as a ready illustration when treating general philosophical problems. The Arabic term nuṭfah for ‘sperm drop’ is introduced in this philosophical discourse from the Quran and other Islamic religious writings. Pre-Islamic Syriac literature, conversely, does not seem to use the corresponding word nuṭptā in this sense. This usage of nuṭptā probably entered the Christian discourse via philosophical and theological writings – rather than from literary genres connected to Quran or Hadith.51

In summary, I have argued that Barhebraeus draws on the illustrations of philosophical problems related to human procreation, especially in Avicenna’s works. The latter conceives of substantial change as sudden and uses human generation as an illustration. The unborn cannot be more or less human, depending on its development. Instead, there must be a distinct point when the unborn stops to be semen and becomes a human being. This understanding of substantial change leaves a mark on Barhebraeus’s presentation of ensoulment as laid out in his later theological summa, the Book of Rays. Here, he argues for ensoulment after the body has been completed rather than when the sperm drop is ‘sown.’ In his earlier Candelabrum of the Sanctuary, Barhebraeus rejects this. Thus, the Avicennan notion of substantial change is vital to Barhebraeus’s understanding of unborn life.

However, in other instances, Barhebraeus deviates from Avicenna’s position. The latter refers to ʿalaqah and muḍġah as distinct embryological stages, following a widespread Islamic terminology in the context of the unborn. Barhebraeus avoids these terms. In his zoology, he posits periods for the embryo’s formation in line with Aristotle instead of Avicenna: 40 days in the case of a male and three months in the case of a female child. These periods mirror Barhebraeus’s reasoning on later ensoulment in the Book of Rays: he explains the duration of the cleansing after birth prescribed in Leviticus 12:2–5 (40 days for a boy, 80 for a girl) as a reflection of the time that a mother carries an inanimate body.

Finally, it is Barhebraeus’s use of the term nuṭptā to refer to the sperm drop that forms a linchpin between his account of the unborn and that of Avicenna. Like Avicenna, he does not use this term in passages explicitly treating biological issues. Throughout the zoology of the Cream of Wisdom, Barhebraeus renders semen as zarʿā. Nevertheless, the term nuṭptā finds its way into his philosophical treatises. The respective passages reflect Barhebraeus’s reception of Avicenna.

This article forms a case study on the complex paths of intellectual exchange that characterized the Syriac Renaissance. In this context, Islamic philosophical texts were one of Syriac-Christian authors’ most important conversation partners. Barhebraeus is an outstanding example of how Christians engaged with the new intellectual developments found in these texts, wrestled with them regarding their heritage, and ultimately developed a new synthesis, which could be seen as faithful to their own tradition but also reflected the debates of their time.

As is known from many studies, Barhebraeus’s distinctiveness lies in his innovative approach of combining, modifying, and reinterpreting various sources. This bricolage technique, assembling and adapting existing materials into a cohesive whole, aligns with his normative provisions on the unborn that I have previously analyzed.52 Ultimately, his regulations on the burial of miscarried children and the sanctioning of abortions can be understood as a pastoral response to the concerns of a Christian community in an Islamic context.

Barhebraeus’ embryological synthesis can be seen as a response to the inquiries of his time just as well. The enduring importance attributed to the unborn is evident not only in Barhebraeus’ writings but also in the works of other authors from various periods. Collectively, these sources highlight the unborn as a central theme in the theological and philosophical discourse of the late antique and medieval intellectual history. The perspectives of Syrian authors, particularly Barhebraeus, are not an exception within this broader panorama. Similar studies on this or other technical terms may reveal yet further instances of such a creative appropriation of Islamic ideas by Christian communities in the Middle Ages.

Bibliography

- Ainsworth, Thomas. “Form vs. Matter.” substantive revision: March 25, 2020. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ed. Edward N. Zalta. Accessed on October 20, 2022. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/form-matter/. .

- Avicenna . Kitāb an-Naǧāh fī l-ḥikmah al-mantiqiyyah wa ‑ṭ ‑ṭabiʿiyyah wa-l-ilāhiyya , ed. Māǧid Faḫrī. B eirut: Dār al-āfāq al-ǧadīdah, 1985. .

- Avicenna. Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ, al-manṭiq 2, al-Maqūlāt , ed. al-Ab Qanawātī [=George Anawati] et al. Cairo: Dār al-kātib al-ʿarabī li-ṭ-ṭibāʿah wa-n-našr, 1959. .

- Avicenna. Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ , al-manṭiq 5, al-Burhān , ed. Abū al-ʿAlā ʿAfīfī and Ibrāhīm Maḏkūr. Cairo: Dār al-kātib al-ʿarabī li-ṭ-ṭibāʿah wa-n-našr, 1956. .

- Avicenna. Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ , aṭ-ṭabīʿiyyāt 8, al-ḥayawān , ed. ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm Muntaṣir et al. Cairo: al-Hayʾah al-miṣriyyah al-ʿāmmah li-t-taʾlīf wa-n-našr, 1970. .

- Bakoš, Ján, ed. Psychologie de Grégoire Aboulfaradj dit Barhebraeus d’après la huitième base de l’ouvrage “Le Candélabre des Sanctuaires” . Leiden: Brill, 1948. .

- Barṣaum, Iġnāṭiyūs Afrām I, ed. L’Entretien de la sagesse par Mar Gregorius Abulfarage Bar Hebraeus Maphrien (catholicos) syrien de l’Orient . Homs, 1940. .

- Beck, Edmund, ed. Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen Contra Haereses . CSCO 169–170. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1957. .

- Bedjan, Paul, ed. Ethicon, seu Moralia Gregorii Barhebraei . Paris: Otto Harrassowitz, 1898. .

- Brandt, Wilhelm. “Mandæans”. In Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Volume VIII , Ed. James Hastings. New York & Edinburg: Charles Scribner’s Sons & T. & T. Clark, p. 380–393. .

- Brock, Sebastian P. “Clothing Metaphors as a Means of Theological Expression in Syriac Tradition.” in Typus, Symbol, Allegorie bei den östlichen Vätern und ihren Parallelen im Mittelalter: Internationales Kolloquium, Eichstätt 1981 , ed. Margot Schmidt and Carl Friedrich Geyer. Regensburg: Pustet, 1982. .

- Brugman, J. and H. J. Drossaart Lulofs, eds. Generation of Animals. The Arabic Translation commonly ascribed to Yaḥyâ ibn al-Biṭrîq . Leiden: Brill, 1971. .

- Chabot, Jean Baptiste, ed. Iacobi Edesseni Hexaemeron seu in opus creationis libri septem. CSCO 92. Paris: Imprimerie Orientaliste L. Durbecq, 1928. .

- Cheikho, Louis, ed. Vingt traités théologiques d’auteurs arabes chrétiens (IXe–XIIIe siècle) . Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1920. .

- Congourdeau, Marie-Hélène. “Debating the Soul in Late Antiquity.” in Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day , ed. Nick Hopwood, Rebecca Flemming, and Lauren Kassell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. .

- Congourdeau, Marie-Hélène. L’embryon et son âme dans les sources Grecques (viᵉ siècle av. J.-C.-vᵉ siècle apr. J.-C.) . Paris: Association des amis du Centre d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance, 2007. .

- Dadikhuda, Davlat. “Not that Simple: Avicenna, Rāzī, and Ṭūsī on the Incorruptibility of the Human Soul at Ishārāt VII.6.” in Islamic Philosophy from the 12th to the 14th Century , ed. Abdelkader Al Ghouz. Göttingen: V&R unipress and Bonn University Press, 2018. .

- Drossaart Lulofs, H.J. “Aristotle, Bar Hebraeus, and Nicolaus Damascenus on Animals.” in Aristotle on Nature and Living Things: Philosophical and Historical Studies Presented to David M. Balme on his Seventieth Birthday , ed. Allan Gotthelf. Pittsburgh, PY: Mathesis Publications; Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1985. .

- Drower, Estel S. and Rudolf Macuch. A Mandaic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963. .

- Eich, Thomas and Doru C. Doroftei: Adam und Embryo . Ergon: Baden-Baden, forthcoming. .

- Eich, Thomas. “Induced Miscarriage in Early Mālikī and Ḥanafī Fiqh .” Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009): 302–336. .

- Eich, Thomas. “Patterns in the History of the Commentation on the So-Called ḥadīth Ibn Masʿūd .” J ournal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 18 (2018): 137–162. .

- Eich, Thomas. “Zur Abtreibung in frühen islamischen Texten.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 170, no. 2 (2020): 345–360. .

- Fancy, Nahyan. “Generation in Medieval Islamic Medicine.” in Reproduction. Antiquity to the Present Day , ed. Nick Hopwood, Rebecca Flemming, and Lauren Kassell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. .

- Fathi, Jean. “Apologie et Mysticisme chez les chrétiens d’Orient: Recherches sur al-Kindī et Barhebraeus (vers 820 & 1280)”. PhD diss., Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2020. .

- Fazzo, Silvia and Mauro Zonta. “Aristotle’s Theory of Causes and the Holy Trinity: New Evidence about the Chronology and Religion of Nicolaus ‘of Damascus’.” Laval théologique et philosophique 64, no. 3 (2008): 681–690. .

- Fazzo, Silvia. “Nicolas, l’auteur du sommaire de la philosophie d’Aristote: Doutes sur son identité, sa datation, son origine.” Revue des Études Grecques 121, no. 1 (2008): 99–126. .

- Filius, Lourus S. ed. The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Historia Animalium. Book i–x of the Kitāb Al-Hayawān. In collaboration with Johannes den Heijer and John N. Mattock. Leiden: Brill, 2019. .

- Furlani, Giuseppe. “Barhebreo sull’ anima razionale (dal Libro del Candelabro del Santuario)” Orientalia N. S. 1 (1932): 1–23, 97–115. .

- al-Ġazālī. Maqāṣid al-falāsifa , ed. Sulaymān Dunyā. Cairo: Dār al-maʿārif bi-Miṣr, 1961. .

- Gibson, M. D. The commentaries of Ishoʿdad of Merv, bishop of Hadatha (c. 850 A.D.) in Syriac and English. 5 vols. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 1911–1916. .

- Graf, Georg. “Philosophisch-theologische Schriften des Paulus al-Râhib, Bischofs von Sidon: Aus dem Arabischen übersetzt.” Jahrbuch für Philosophie und spekulative Theologie 20 (1906): 55–80, 160–179. .

- Gutas, Dimitri. Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna’s Philosophical Works . Second, Revised and Enlarged Edition, Including an Inventory of Avicenna’s Authentic Works . Leiden: Brill, 2014. .

- Halim, Fachrizal A. Legal Authority in Premodern Islam. Yaḥyā b. Sharaf al-Nawawī in the Shāfiʿī School of Law . London: Routledge, 2015. .

- Hugonnard-Roche, Henri. “La question de l’âme dans la tradition philosophique syriaque (VIe–IXe siècle) .” Studia graeco-arabica 4 (2014): 17–64. .

- Holmes Katz, Marion. “The Problem of Abortion in Classical Sunni fiqh .” I n Islamic Ethics of Life: Abortion, War, and Euthanasia , ed. Jonathan E. Brockopp. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2003. .

- Horten, Max. “Paulus, Bischof von Sidon (XIII. Jahrhundert). Einige seiner philosophischen Abhandlungen .” Philosophisches Jahrbuch 19 (1906): 144–166. .

- Jäckel, Florian. “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”: Vorstellungen ungeborenen Lebens bei Bar ʿEbrāyā (1226 –1286 n. Chr.) . Ergon: Baden-Baden, 2022. .

- Jäckel, Florian. Re-Negotiating Interconfessional Boundaries through Intertextuality: The Unborn in the Kṯābā ḏ- Huddāyē of Barhebraeus (d. 1286).” M edieval Encounters 26 (2020): 95–127. .

- Janssens, Herman F. “Bar Hebraeus’ Book of the Pupils of the Eye .” The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 47, no. 1 (1930): 26–49, 47, no. 2 (1931): 94–134, 48, no. 4 (1932): 209–263, 52, no. 1 (1935): 1–21. .

- Janssens, Herman F., ed. L’Entretien de la Sagesse: Introduction aux œuvres philosophiques de Bar Hebraeus . Liège: Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres; Paris: Librairie E. Droz, 1937. .

- Kalbarczyk, Alexander. Predication and Ontology: Studies and Texts on Avicennian and Post-Avicennian Readings of Aristotle’s Categories . Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018. .

- Kiraz, George A., ed. Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition . Accessed October 20, 2022. https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/index.html. .

- Kruk, Remke, ed. The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Parts of Animals. Book XI–XIV of the Kitāb al-Ḥayawān : A Critical Edition with Introduction and Selected Glossary . Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1979. .

- Lagarde, Paul, ed. Praetermissorum Libri Duo . Göttingen: Dieterich, 1879. .

- McGinnis, Jon. “On the Moment of Substantial Change: A Vexed Question in the History of Ideas.” In Interpreting Avicenna: Science and Philosophy in Medieval Islam: Proceedings of the Second Conference of the Avicenna Study Group , ed. Jon McGinnis. Leiden: Brill, 2004. .

- McGinnis, Jon. Avicenna . Great Medieval Thinkers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. .

- McGinnis, Jon, ed. and trans. Avicenna. The Physics of The Healing. Books I & II. A parallel English-Arabic text . Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005. .

- Muraoka, Takamitsu, ed. and trans. Jacob of Serugh’s Hexaemeron. Louvain: Peeters, 2018. .

- Platti, Emilio. “‘L’entretien de la sagesse’ de Barhebraeus: La traduction arabe,” MIDEO 18 (1988): 153–194. .

- Reller, Jobst. “Iwannis von Dara, Mose bar Kepha und Bar Hebräus über die Seele, traditionsgeschichtlich untersucht.” in After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J.W. Drijvers , ed. G.J. Reinink and A.C. Klugkist. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters and Departement Oosterse Studies, 1999. .

- Rubens Duval, ed. Lexicon Syriacum auctore Hassano Bar Bahlule , 3 vols. Paris: Reipublicae typographaeum, 1901. .

- Schmitt, Jens Ole, ed. Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Physics: Introduction, Edition, Translation, and Commentary . Leiden: Brill, forthcoming. .

- Shemunkasho, Aho, ed. and trans. John of Dara On the Resurrection of Human Bodies, Bibliotheca Nisibinensis 4. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2020. .

- Shihadeh, Ayman. “New Light on the Reception of al-Ghazālī’s Doctrines of the Philosophers ( Maqāṣid al-Falāsifa ).” In In the Age of Averroes: Arabic Philosophy in the Sixth/Twelfth Century , ed. Peter Adamson. London: Warburg Institute, 2011. .

- Steyer, Curt, ed. Buch der Pupillen von Gregor Bar Hebräus . Leipzig: August Pries, 1908. .

- Studtmann, Paul. “Aristotle’s Categories.” S ubstantive revision: February 2, 2021. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ed. Edward N. Zalta. Accessed on October 20, 2022. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-categories/. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi. “Reception of Islamic Theology among Syriac Christians in the Thirteenth Century: The Use of Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī in Barhebraeus’ Candelabrum of the Sanctuary .” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 2 (2014): 170–192. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi. “The Influence of al-Ghazālī on the Juridical, Theological and Philosophical Works of Barhebraeus.” in Islam and Rationality , ed. Georges Tamer. Leiden: Brill, 2015. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi. “The Reception of Ibn Sīnā in Syriac: The Case of Gregory Barhebraeus.” in Before and After Avicenna: Proceedings of the First Conference of the Avicenna Study Group , ed. David C. Reisman, with the assistance of Ahmed H. Al‑Rahim. Leiden: Brill, 2003. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi. “Barhebraeus und seine islamischen Quellen. Têḡraṯ têḡrāṯā (Tractatus tractatuum) und Ġazālīs Maqāṣid al-falāsifa.” In Syriaca. Zur Geschichte, Theologie, Liturgie und Gegenwartslage der syrischen Kirchen , ed. Martin Tamcke. Münster, Hamburg, and London: LIT, 2002. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi. Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography . Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2013. .

- Takahashi, Hidemi, ed. Aristotelian Meteorology in Syriac. Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Books of Mineralogy and Meteorology . Leiden: Brill, 2004. .

- Teule, Herman. “The Interaction of Syriac Christianity and the Muslim World in the Period of the Syriac Renaissance .” in Syriac Churches Encountering Islam: Past Experiences and Future Perspectives , ed. Dietmar W. Winkler. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2010. .

- Thijssen, Johannes M. “Twins as Monsters: Albertus Magnus’s Theory of the Generation of Twins and its Philosophical Context .” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 61, no. 2 (1987): 237–246. .

- Thom, Paul. “The division of the categories according to Avicenna.” In Aristotle and the Arabic Tradition , ed. Ahmed Alwishah and Josh Hayes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. .

- Toepel, Alexander. Die Adam- und Seth-Legenden im syrischen Buch der Schatzhöhle: Eine quellenkritische Untersuchung , CSCO 618. Louvain: Peeters, 2006. .

- al-ʿUṯaymīn, Muḥammad b. Sālih. Šarḥ al-arbaʿīn an-nawawīyah . Riyadh: Dār aṯ-ṯurayyā li-n-našr wa-tawzīʿ, 2004. .

- Vaschalde, Arthur, ed. Babai Magni Liber de Unione . CSCO 79–80. Louvain: Imprimerie Orientaliste L. Durbecq, 1953. .

- Vaschalde, Arthur, ed. Iacobi Edesseni Hexaemeron seu in opus creationis libri septem. CSCO 97. Leuven: Typographeum Marcelli Istas, 1932. .

- Weisser, Ursula. Das „Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung“ von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana . Berlin: De Gruyter, 1980. .

- Weisser, Ursula, ed. Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung und die Darstellung der Natur (Buch der Ursachen) . Aleppo: Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo, 1979. .

- Weisser, Ursula. Zeugung, Vererbung und pränatale Entwicklung in der Medizin des arabisch-islamischen Mittelalters . Erlangen, 1983. .

- Wensinck, A.J., ed. and trans. Bar Hebraeus’s Book of the Dove: Together with some chapters from his Ethikon (Leyden: E.J. Brill, 1919). .

- Yešūʿ b. Gabriel, ed. Ktābā d-Zalgē w-šurārā d-šetēssē ʿēdtānyātā – Book of Zelge by Bar-Hebreaus [sic] . Mor Gregorius Abulfaraj the Great Syrian Philosopher and Author of Several Christian Works 1226–1286 . Istanbul, 1997. .

- Zalta, Edward N., ed. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Accessed October 20, 2022. . .

Footnotes

1 See Herman Teule, “The Interaction of Syriac Christianity and the Muslim World in the Period of the Syriac Renaissance,” in Syriac Churches Encountering Islam: Past Experiences and Future Perspectives, ed. Dietmar W. Winkler (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2010). For a comprehensive overview of Barhebraeus’s works, see Hidemi Takahashi, Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2013). If not stated otherwise, for most Syriac sources and their authors mentioned in this paper, a brief overview is openly accessible in George A. Kiraz, ed., Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, accessed October 20, 2022, https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/index.html. For the area of philosophy, the same holds true for Edward N. Zalta, ed., Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed October 20, 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/index.html.

2 For Barhebraeus’s reception of Islamic philosophy, see, e.g., Hidemi Takahashi, “The Reception of Ibn Sīnā in Syriac: The Case of Gregory Barhebraeus,” in Before and After Avicenna: Proceedings of the First Conference of the Avicenna Study Group, ed. David C. Reisman, with the assistance of Ahmed H. Al‑Rahim (Leiden: Brill, 2003) and id., “Reception of Islamic Theology among Syriac Christians in the Thirteenth Century: The Use of Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī in Barhebraeus’ Candelabrum of the Sanctuary,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 2 (2014): 170–192. For Avicenna, see Jon McGinnis, Avicenna, Great Medieval Thinkers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) and Dimitri Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna’s Philosophical Works, Second, Revised and Enlarged Edition, Including an Inventory of Avicenna’s Authentic Works (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

3 Barhebraeus, Discourse of Wisdom 2.18 (text: Herman F. Janssens, ed., L’Entretien de la Sagesse: Introduction aux œuvres philosophiques de Bar Hebraeus (Liège: Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres; Paris: Librairie E. Droz, 1937), 79.5–8; translation: ibid., 233). All translations are my own, if not stated otherwise. For the Discourse of Wisdom, see the introduction of Janssens’s edition. The premodern Arabic translation of this difficult text should be taken into consideration as well, cf. Emilio Platti, “‘L’entretien de la sagesse’ de Barhebraeus: La traduction arabe” MIDEO 18 (1988): 153–194; Iġnāṭiyūs Afrām I Barṣaum, ed., L’Entretien de la sagesse par Mar Gregorius Abulfarage Bar Hebraeus Maphrien (catholicos) syrien de l’Orient (Homs, 1940). As Jean Fathi has recently argued, this Arabic translation might have been undertaken by Barhebraeus himself, cf. Jean Fathi, “Apologie et Mysticisme chez les chrétiens d’Orient: Recherches sur al-Kindī et Barhebraeus (vers 820 & 1280)” (PhD diss., Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2020), 257–259. This will need further research. For the metaphor of clothing in the earlier Syriac tradition, which might have inspired Barhebraeus here, see Sebastian P. Brock, “Clothing Metaphors as a Means of Theological Expression in Syriac Tradition,” in Typus, Symbol, Allegorie bei den östlichen Vätern und ihren Parallelen im Mittelalter: Internationales Kolloquium, Eichstätt 1981, ed. Margot Schmidt and Carl Friedrich Geyer (Regensburg: Pustet, 1982).

4 For the concept of hylomorphism behind coming-to-be and passing-away, see Thomas Ainsworth, “Form vs. Matter”, substantive revision: March 25, 2020, in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, accessed on October 20, 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/form-matter/.

5 For the categories, see Paul Studtmann, “Aristotle’s Categories,” substantive revision: February 2, 2021, in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, accessed on October 20, 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/form-matter/. For categories in Avicenna and post-Avicennan works see Alexander Kalbarczyk, Predication and Ontology: Studies and Texts on Avicennian and Post-Avicennian Readings of Aristotle’s Categories (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), with further literature in n. 6 on p. 4.

6 The term ‘gradually’ might imply a change by degrees, i.e. step-by-step, which would thus not be continuous. The sources themselves show some inconsistencies regarding this point (cf. text [3] below). This is pointed out by Jens Ole Schmitt, ed., Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Physics: Introduction, Edition, Translation, and Commentary (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming), section “I.4.8.5 Definitions and Categories of Motion”.

7 Barhebraeus, Cream of Wisdom, Book of Categories 3.3.6. The text is not edited. Translation based on ms. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Or. 69, (dated 1340), fol. 35v. The ms. forms a unit with Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Or. 83. Both are freely accessible online. For these mss. see Hidemi Takahashi, ed., Aristotelian Meteorology in Syriac. Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Books of Mineralogy and Meteorology (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 15–16, 585–588, and 601–604. For the Cream of Wisdom in general, see his introduction. The idea of the right aptitude to receive the form can also be found in Barhebraeus’s Treatise of treatises. This, his medium-length summa, is one of the least studied among his works; see Hidemi Takahashi, “Barhebraeus und seine islamischen Quellen. Têḡraṯ têḡrāṯā (Tractatus tractatuum) und Ġazālīs Maqāṣid al-falāsifa,” in Syriaca. Zur Geschichte, Theologie, Liturgie und Gegenwartslage der syrischen Kirchen, ed. Martin Tamcke (Münster, Hamburg, and London: LIT 2002). In a passage on ensoulment, Barhebraeus compares the process to the lightening of a candle wick: if the wick has the right quality, it is lit by the flame and thus becomes a light or lamp. This text is not edited either; for the mentioned passage see ms. Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, hmml project n° CCM 00382 (dated 18th/19th century), fol. 89r–v (available online: https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/132501); cf. Florian Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”: Vorstellungen ungeborenen Lebens bei Bar ʿEbrāyā (1226 –1286 n. Chr.) (Ergon: Baden-Baden, 2022), https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956509278, 268. However, the terms semen or drop do not appear in the Treatise.

8 Barhebraeus, Book of the Pupils of the Eye 2.2 (“On Change”) (text: Herman F. Janssens, “Bar Hebraeus’ Book of the Pupils of the Eye,” The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 47, no. 1 (1930): 26–49, 47, no. 2 (1931): 94–134, 48, no. 4 (1932): 209–263, 52, no. 1 (1935): 1–21, here: 47, no. 1 (1930): 119.7–15; translation: ibid., 52, no. 1 (1935): 15). Cf. the edition Curt Steyer, ed., Buch der Pupillen von Gregor Bar Hebräus (Leipzig: August Pries, 1908), 8. For the Book of the Pupils of the Eye, see the introductions of the two editions. The question of various terms for ‘change,’ which Barhebraeus uses (and comments upon) in his different works needs further study. In this regard, there are two further passages in the Cream of Wisdom: Book on Coming-to-Be and Passing-Away 1.1.1 as well as Physics 3.4.1. These are discussed by Schmitt, Butyrum Sapientiae, Physics, section “I.4.8.5 Definitions and Categories of Motion”. In what follows in the Book of Categories of the Cream after text [2] cited above, Barhebraeus states that substantial changes are metaphorically called ‘jumps’ or ‘jerks’ (zuʿē) in the ‘old writings’. Originally, I had read ‘old writings’ as Barhebraeus’s attempt to mask the origin of this terminology of ‘jumps’ as Avicennan; cf., however, below, n. 15.

9 The exact dating of these two works is uncertain; cf. the chronology of Barhebraeus’s works in Takahashi, A Bio-Bibliography, 90–94.

10 Barhebraeus, Candelabrum of the Sanctuary 8.3.1.2 (text: Ján Bakoš, ed., Psychologie de Grégoire Aboulfaradj dit Barhebraeus d’après la huitième base de l’ouvrage “Le Candélabre des Sanctuaires” (Leiden: Brill, 1948), Syr. 71–72; translation: ibid., 42). For the part of the Candelabrum treating the soul, see Giuseppe Furlani, “Barhebreo sull’ anima razionale (dal Libro del Candelabro del Santuario)” Orientalia N. S. 1 (1932): 1–23, 97–115, the introduction in Bakoš, Psychologie de Grégoire Aboulfaradj as well as Jobst Reller, “Iwannis von Dara, Mose bar Kepha und Bar Hebräus über die Seele, traditionsgeschichtlich untersucht,” in After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J.W. Drijvers, ed. G.J. Reinink and A.C. Klugkist (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters and Departement Oosterse Studies, 1999), 264–267. For Syriac works on the soul up until the 9th century, see Henri Hugonnard-Roche, “La question de l’âme dans la tradition philosophique syriaque (VIe–IXe siècle),” Studia graeco-arabica 4 (2014): 17–64. For the Greek context, especially with reference to the ensoulment of the unborn, see Marie-Hélène Congourdeau, L’embryon et son âme dans les sources Grecques (viᵉ siècle av. J.-C.-vᵉ siècle apr. J.-C.) (Paris: Association des amis du Centre d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance, 2007) and, generally for late antiquity, id., “Debating the Soul in Late Antiquity,” in Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day, ed. Nick Hopwood, Rebecca Flemming, and Lauren Kassell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). To my knowledge, there is no systematic study of ensoulment or the soul in later Syriac or Christian-Arabic works.

11 Barhebraeus, Book of Rays 6.3.1. The Book of Rays has not been critically edited. I translate according to ms. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Sachau 327 (dated 17th cent.), fol. 80r–v, which is freely accessible online. The only edition available contains an error here (as well as in other places), cf. Yešūʿ b. Gabriel, ed., Ktābā d-Zalgē w-šurārā d-šetēssē ʿēdtānyātā – Book of Zelge by Bar-Hebreaus [sic]. Mor Gregorius Abulfaraj the Great Syrian Philosopher and Author of Several Christian Works 1226–1286 (Istanbul, 1997), 149. That there is a difference between Barhebraeus’s position on ensoulment in the Candelabrum and in the Book of Rays had been pointed out by Oskar Braun, ed., Moses Bar Kepha und sein Buch von der Seele (Freiburg i. Br.: Herdersche Verlagshandlung, 1891), 139–140, however without any further explanations. It is also important to note that Barhebraeus’s principial idea of ensoulment with the body has not changed. Rather, the notion of body as ‘completed body’ and the idea of substance have been specified. Also, it is noteworthy that my translation of tarmitā is rather literal. The word is used in conjunction with zarʿā, i.e. seed, to mean sowing and in this respect also for ‘conception.’ However, Barhebraeus renders ‘conception’ mostly as baṭnā.

12 The interpretation of the human soul as the substantial form of a human being is explicit in Barhebraeus, Discourse of Wisdom 2.32 (text: Janssens, L’Entretien de la Sagesse, 89.8–12; translation: ibid., 257). This identification of soul and form is philosophically problematic in the case of the human soul; cf., e.g., Davlat Dadikhuda, “Not that Simple: Avicenna, Rāzī, and Ṭūsī on the Incorruptibility of the Human Soul at Ishārāt VII.6,” in Islamic Philosophy from the 12th to the 14th Century, ed. Abdelkader Al Ghouz (Göttingen: V&R unipress and Bonn University Press, 2018). Barhebraeus thus qualifies the relationship of body and soul in the same context of the Discourse of Wisdom 2.32 as “love and leadership” rather than “composition and mixture” (w-b-[ʾ]esārā d-šengtā w-malāḥutā w-lā hwā d-ḥabbikuta w-da-mmazgutā).

13 “If a woman conceives and bears a male child, she shall be ceremonially unclean for seven days; as at the time of her menstruation, she shall be unclean. On the eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised. Her time of blood purification shall be thirty-three days; she shall not touch any holy thing, or come into the sanctuary, until the days of her purification are completed. If she bears a female child, she shall be unclean for two weeks, as in her menstruation; her time of blood purification shall be sixty-six days” (quoted according to the New Revised Standard Version).

14 This explanation by Philoxenos is only attested indirectly as of yet. It is mentioned, among other places, in Moses bar Kepha’s (d. 903) Mēmrā on the Soul, which is Barhebraeus’s Vorlage for the Candelabrum. Tracing Barhebraeus’s entire reworking of these passages (first, of Moses’s Mēmrā for the Candelabrum, then the latter for the Book of Rays) is beyond the scope of this article. At any rate, Moses and Barhebraeus mention other Greek and Syriac authors, who either put forth the simultaneity of body and soul or later ensoulment. For a detailed analysis of these points see chapter 4 in Florian Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”, 215–288.

15 Jon McGinnis, “On the Moment of Substantial Change: A Vexed Question in the History of Ideas,” in Interpreting Avicenna: Science and Philosophy in Medieval Islam: Proceedings of the Second Conference of the Avicenna Study Group, ed. Jon McGinnis (Leiden: Brill, 2004); see also id., Avicenna, 84–88. I would like to correct McGinnis’s suggestion (“Moment of Substantial Change,” 56) that Avicenna refers so substantial changes as ‘jumps’ or ‘jerks’ (Arabic iḫtilāǧāt). The passage he scrutinizes is part of Avicenna’s treatment of the generation of twins. In this context, the male emission of semen is described as distinct ‘jerks’ resulting in distinct embryos, see Ursula Weisser, Zeugung, Vererbung und pränatale Entwicklung in der Medizin des arabisch-islamischen Mittelalters (Erlangen, 1983), 163–164 and Johannes M. Thijssen, “Twins as Monsters: Albertus Magnus’s Theory of the Generation of Twins and its Philosophical Context,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 61, no. 2 (1987): 237–246.

16 McGinnis, “Moment of Substantial Change,” 42–48.

17 ʿAlaqah is often translated as ‘bloodclot’ or ‘leech’ and muḍġah as ‘piece of flesh’ or ‘embryo’. It is best, I believe, not to impose modern concepts of embryological developments on these kinds of texts. On the other hand, Avicenna (and other later authors) seem to treat them as technical terms for distinct embryological stages. This is why translations that convey the original meaning, such as ‘clinging thing’ for ʿalaqah, do not resolve this problem either. For this reason, I have left these words untranslated.

18 Avicenna, Book of the Healing: Physics 2.3 (text + translation: Jon McGinnis, ed. and trans., Avicenna. The Physics of The Healing. Books I & II. A parallel English-Arabic text (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005), Arabic 141, 141. For the Book of the Healing, see Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition, 103–115.

19 For the Book of the Healing as Vorlage for Barhebraeus’s Cream of Wisdom, see Takahashi, Aristotelian Meteorology in Syriac, 11–14 and 48–50. The present case is also an example of Barhebraeus’s rearrangement of material in his sources: Avicenna had come to the conclusion that the question of movement and change should not be dealt with within logic, i.e. the Categories; cf. Avicenna, Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ, al-manṭiq 2, al-Maqūlāt, ed. al-Ab Qanawātī [=George Anawati] et al. (Cairo: Dār al-kātib al-ʿarabī li-ṭ-ṭibāʿah wa-n-našr, 1959), 271.3–9. He only mentions that changes in substance are to be treated differently than in other categories; ibid., 271.11–12. Accordingly, Avicenna treats the question in the Physics of the Healing; cf. Paul Thom, “The division of the categories according to Avicenna,” in Aristotle and the Arabic Tradition, ed. Ahmed Alwishah and Josh Hayes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 38. In the Cream of Wisdom (text [2] above), Barhebraeus reverts to treating the problem in the Book of Categories, but he uses Avicenna’s correspondent text from the Physics of the Book of the Healing (text [5]).

20 There seems to be no direct equivalent for Arabic manīy in Syriac, apart from verbal expressions using the root r-m-y with the general meaning of ‘to throw’ as well as ‘to set.’ To this effect, Barhebraeus’s use of the cognate tarmitā in text [4] above is noteworthy. In general, the texts I looked at do not seem to provide a consistent terminology with regard to the semen. In specific passages, the male and female contributions to generation are meticulously distinguished, functionally and terminologically, and later referred to again as the ‘two seeds;’ cf. also Weisser, Zeugung, Vererbung und pränatale Entwicklung, 117–140.

21 Avicenna, Book of the Healing: Physics 2.3 (text + translation: McGinnis, The Physics of The Healing, 141, Arabic 141).

22 I specifically refer to ʿalaqah and muḍġah. Naturally, bones and nerves/sinews appear in medical texts as well, but figure in Hadith texts, too. In general, cf. Quran 23:12–14 as an example. A key text is one of the Forty Ḥadiths by an-Nawawī (1233–1277): “Indeed, each one of you—his figure/creation (ḫalq) is gathered in the belly of his mother for forty days as a drop (nuṭfah), then it is (yakūn) a ʿalaqah likewise [i.e. forty days?], then it is a muḍġah likewise [i.e. forty days?], then the angel is sent to him and he blows into him the spirit (rūḥ) […];” translated according to Muḥammad b. Sālih al-ʿUṯaymīn, Šarḥ al-arbaʿīn an-nawawīyah (Riyadh: Dār aṯ-ṯurayyā li-n-našr wa-tawzīʿ, 2004), 99. For an-Nawawī, see Fachrizal A. Halim, Legal Authority in Premodern Islam. Yaḥyā b. Sharaf al-Nawawī in the Shāfiʿī School of Law (London: Routledge, 2015), 14–34. For research on the unborn in Islamic religious texts see Thomas Eich, “Induced Miscarriage in Early Mālikī and Ḥanafī Fiqh,” Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009): 302–336; id., “Patterns in the History of the Commentation on the So-Called ḥadīth Ibn Masʿūd,” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 18 (2018): 137–162; id., “Zur Abtreibung in frühen islamischen Texten,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 170, no. 2 (2020): 345–360; and Marion Holmes Katz, “The Problem of Abortion in Classical Sunni fiqh,” in Islamic Ethics of Life: Abortion, War, and Euthanasia, ed. Jonathan E. Brockopp (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2003).

23 Apart from Avicenna’s Book of the Healing and Aristotle’s History of Animals, Faḫr ad-Dīn ar-Rāzī’s (1150–1210) Eastern Investigations (al-Mabāḥiṯ al-mašriqiyyah) are another source for Barhebraeus treatment of procreation and embryology. For details, see Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”, 122–209. That Barhebraeus’s account actually corresponds with the compendium On the Philosophy of Aristotle dubiously ascribed to Nicolaus of Damascus must be considered as well. However, the zoological parts of this work are only transmitted in small fragments and can thus not be used for comparison; cf. H.J. Drossaart Lulofs, “Aristotle, Bar Hebraeus, and Nicolaus Damascenus on Animals,” in Aristotle on Nature and Living Things: Philosophical and Historical Studies Presented to David M. Balme on his Seventieth Birthday, ed. Allan Gotthelf (Pittsburgh, PY: Mathesis Publications; Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1985). For the wrong attribution of Nicolaus’s compendium see Silvia Fazzo and Mauro Zonta, “Aristotle’s Theory of Causes and the Holy Trinity: New Evidence about the Chronology and Religion of Nicolaus ‘of Damascus’,” Laval théologique et philosophique 64, no. 3 (2008): 681–690 and Silvia Fazzo, “Nicolas, l’auteur du sommaire de la philosophie d’Aristote: Doutes sur son identité, sa datation, son origine,” Revue des Études Grecques 121, no. 1 (2008): 99–126.

24 Cf. Avicenna, Book of the Healing: Book of Animals 9.5 (“On the Distinction of Alterations of the Matter of the Embryo until it is Completed”) (text: Ibn Sīnā, Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ, aṭ-ṭabīʿiyyāt 8, al-ḥayawān, ed. ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm Muntaṣir et al. (Cairo: al-Hayʾah al-miṣriyyah al-ʿāmmah li-t-taʾlīf wa-n-našr, 1970), 172–178.

25 Cream of Wisdom: Book of Animals 5.2 (text: Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”, 341–343; translation: ibid., 356–358).

26 “The body of the embryo becomes similar to a leech/clinging thing,” l-ʿellaqtā metdammē gšum ʿulā.

27 Barhebraeus, Cream of Wisdom: Book of Animals 5.1.2 (text: Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”, 338; translation: ibid., 354) and Aristotle, History of Animals VII.3 (583b14–23 Bekker).

28 Cf. Book of the Healing: Book of Animals 9.5 (text: Ibn Sīnā, ed. Muntasir et al., 172.4–173.19). In this same context, Avicenna treats the embryological stages ʿalaqah and muḍġah.

29 In the passages treated in this article, Barhebraeus’s engagement with the Syriac tradition is rather implicit (cf. fn. 14 above). For a more detailled analysis see Chapter 4 in Jäckel, “Wenn wir sagen, dass der Tropfen Mensch wird”, especially 269–285.

30 For a search as comprehensive as possible I have used the dictionaries by Brockelmann and Payne-Smith, which both refer to attestations in the sources, as well as the digital thesaurus Simtho (see Beth Mardutho, ed., Simtho: The Syriac Thesaurus, accessed on October 20, 2022, http://bethmardutho.org/simtho/) and the Digital Syriac Corpus (see James E. Walters, ed., “About the Digital Syriac Corpus,” accessed on October 20, 2022, https://syriaccorpus.org/index.html).

31 Bar Bahlul, Lexicon s.v. nuṭptā (text: Rubens Duval, ed., Lexicon Syriacum auctore Hassano Bar Bahlule, 3 vols. (Paris: Reipublicae typographaeum, 1901), vol. 2, col. 1225).

32 Eliya of Nisibis, Book of the Translator 21 (text: Paul Lagarde, ed., Praetermissorum Libri Duo (Göttingen: Dieterich, 1879), 47). I am grateful to Nicolas Atas for pointing this out to me.

33 Ephrem the Syrian, Hymns against Heresies 49.4 (text: Edmund Beck, ed., Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen Contra Haereses, CSCO 169 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1957), 193.1–4; translation: id., ed. and trans., Des Heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymnen Contra Haereses, CSCO 170 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1957, 170–171) and Babai the Great, Book of Union 1.3 (text: Arthur Vaschalde, ed., Babai Magni Liber de Unione, CSCO 79 (Louvain: Imprimerie Orientaliste L. Durbecq, 1953), 20.15–17; translation: id., ed. and trans., Babai Magni Liber de Unione, CSCO 80 (Louvain: Imprimerie Orientaliste L. Durbecq, 1953), 16–17).

34 Cf. Alexander Toepel, Die Adam- und Seth-Legenden im syrischen Buch der Schatzhöhle: Eine quellenkritische Untersuchung, CSCO 618 (Louvain: Peeters, 2006), 56.

35 Jacob of Serugh, Hexaemeron Day 6 (text + translation: Takamitsu Muraoka, ed. and trans., Jacob of Serugh’s Hexaemeron (Louvain: Peeters, 2018), 186–187, l. 505–510) and Jacob of Edessa, Hexaemeron Day 7 (text: Jean Baptiste Chabot, ed., Iacobi Edesseni Hexaemeron seu in opus creationis libri septem, CSCO 92 (Paris: Imprimerie Orientaliste L. Durbecq, 1928), 331.ii–333.ii; translation: Arthur Vaschalde, ed., Iacobi Edesseni Hexaemeron seu in opus creationis libri septem, CSCO 97 (Leuven: Typographeum Marcelli Istas, 1932), 283.24–284.3).

36 A notable instance of nuṭptā in a Syriac text is John of Dara’s (fl. ca. 800–860) Mēmrā on the Resurrection of Human Bodies 1.4.4 (text: Aho Shemunkasho, ed. and trans., John of Dara On the Resurrection of Human Bodies, Bibliotheca Nisibinensis 4 (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2020), 109; translation: ibid., 370). I am grateful to the editor for sharing the passages with me. I only give a brief analysis: John of Dara compares God’s power to raise the dead with his power in creating humankind. The latter is paralleled with human procreation – similar to the Hexaemera of the two Jacobs (cf. n. 34 above). John uses zarʿā in almost all cases, which mirrors, e.g., the terminology of his contemporary Moses bar Kepha. When John speaks of the ‘miracle’ of procreation, the human seed is figuratively called “a little drop” (nuṭptā zʿortā), which is “foul” (ndid) and “dishonorable (škir) to approach.” Strikingly, this resembles a locus classicus of embryological motives in Rabbinic literature, i.e. Pirkei Avot 3.1. On the other hand, John portrays the development of the unborn after the mingling of the drop and menstrual blood with almost the same motives as contemporaneous Islamic discourse (cf. n. 22 above). Further, an instance of the term nuṭptā d-zarʿā can be found in Išoʿdād of Merv (fl. ca. 850), where he refers to the Greek mythology of Chronos’s semen falling into the sea; cf. Išoʿdād of Merv, Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, ad. 13 (text: M. D. Gibson, The commentaries of Ishoʿdad of Merv, bishop of Hadatha (c. 850 A.D.) in Syriac and English, 5 vols. (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 1911–1916), vol. 4, 25; translation: ibid., Syriac 34. Regarding the references given for niṭupta in E.S. Drower and R. Macuch, A Mandaic Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), 298, the only one establishing a connection to sperm is W. Brandt, “Mandæans”, in Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. 8, p. 382; I would like to express my gratitude to one of the reviewers for pointing me into this direction. In general, this suggests a lively transcommunal discussion of the unborn in the context of creation and resurrection in early Islamic times, which will need further research. A possible echo of this interaction can be seen in Barhebraeus’s reference to the “foul drop” (nuṭptā ndidtā) in his Book of the Dove, I.4 (text: Paul Bedjan, ed., Ethicon, seu Moralia Gregorii Barhebraei (Paris: Otto Harrassowitz, 1898), 527; translation: A.J. Wensinck, ed. and trans., Bar Hebraeus’s Book of the Dove: Together with some chapters from his Ethikon (Leyden: E.J. Brill, 1919), 9). Here, Barhebraeus likely draws on al-Ġazālī’s expression nuṭfah qaḏirah in his Revival of the Religious Sciences, cf. ibid., 9, n. 2.

37 An analysis of this Quranic material by the ERC-Project Contemporary Bioethics and the History of the Unborn in Islam (University of Hamburg) will be available in Thomas Eich and Doru C. Doroftei: Adam und Embryo (Ergon: Baden-Baden, forthcoming). My research on Barhebraeus was part of this larger project.

38 This ‘Islamic’ embryology is distinct in that key terms and notions are employed throughout. However, it should not be conceived as totally self-contained and uniform. See the references in n. 22 above and also Nahyan Fancy, “Generation in Medieval Islamic Medicine,” in Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day, 129–140.

39 In case of the On the Generation of Animals, there was a Syriac translation that is no longer extant, but it is not considered to be an intermediary for the Arabic translation; see Remke Kruk, ed., The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Parts of Animals. Book XI–XIV of the Kitāb al-Ḥayawān: A Critical Edition with Introduction and Selected Glossary (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1979), 24–31 and Lourus S. Filius, ed., The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Historia Animalium. Book i–x of the Kitāb Al-Hayawān, in collaboration with Johannes den Heijer and John N. Mattock (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 4–6, 8–14. In the case of the Book of the Secret of Creation, the exact Vorlage is not known; see Ursula Weisser, Das „Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung“ von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1980), 48–54.

40 Pseudo-Apollonios of Tyana, Book of the Secret of Creation IV.3.2 (text: Ursula Weisser, ed., Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung und die Darstellung der Natur (Buch der Ursachen) (Aleppo: Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo, 1979), Arabic 318.11–319.2; German paraphrase: id., Das „Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung“, 117). Further accounts of nuṭfah can be found in the comprehensive index of the edition.

41 Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana, Book of the Secret of Creation Prologue (text: Weisser, Darstellung der Natur, Arabic 3; German Paraphrase: id., Das „Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung“ , 74).

42 Aristotle, On the Generation of Animals (premodern Arabic translation) IV.4 (769b31–770a23 Bekker). In three more cases, nuṭfah is used to translate Greek sperma and kuēma (772a10, 772a19 and 772b18 Bekker, respectively). For the translation of Aristotle’s zoological works, see the introductions in J. Brugman and H. J. Drossaart Lulofs, eds., Generation of Animals. The Arabic Translation commonly ascribed to Yaḥyâ ibn al-Biṭrîq (Leiden: Brill, 1971); Kruk, The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Parts of Animals, and Filius, The Arabic Version of Aristotle’s Historia Animalium.

43 Weisser dates the Book of the Secret of Creation to the 8th century; Weisser, Darstellung der Natur, 3. Comparing its more fluid usage of nuṭfah with the slightly later writings by John of Dara (cf. n. 35 above) and the Arabic translation of the On the Generation of Animals (dated at around 850), one is tempted to assume a gradual consolidation of the meaning of ‘drop’ meaning specifically ‘the human semen.’ This will need further research.

44 This is not to say that the content of Avicenna’s ideas of embryology can be conceived as ‘Islamic’ in a narrower, religious sense. However, his usage of terms such qarār for the womb (cf. Quran 23:12–14), which he uses in the context of text [8] below, clearly betray his Islamic background.

45 Avicenna, Book of the Healing: Book on Demonstrative Proof 2.9 (text: Ibn Sīnā, Kitāb aš-Šifāʾ, al-manṭiq 5, al-Burhān, ed. Abū al-ʿAlā ʿAfīfī and Ibrāhīm Maḏkūr (Cairo: Dār al-kātib al-ʿarabī li-ṭ-ṭibāʿah wa-n-našr, 1956), 182.8–9).

46 On this topic in Avicenna’s philosophy see McGinnis, Avicenna, 27–52.

47 Avicenna, Book of the Healing: Physics 1.11 (text + translation: McGinnis, The Physics of The Healing, Arabic 73, 73). McGinnis translates al-ḥāṣil fī n-nuṭfah as what “exists in the semen.” This is misleading, as the semen itself does not have human form. A more accurate translation would be “exists in the semen [potentially].”

48 I add one last example from Avicenna’s Book of the Salvation, where, again, the connection of demonstrative proofs and causal theories is discussed. Here, a carpenter and a father are presented as effective cause and principle of movement for the chair and the child (ṣabī), respectively. Accordingly, the material cause is the wood or the menstrual blood: Avicenna, Book of the Salvation: Book of Demonstrative Proof “On the Divisions of Causes and on the Proof of their Introduction into Definition and Demonstrative Proof” (text: Ibn Sinā, Kitāb an-Naǧāh fī l-ḥikmah al-mantiqiyyah wa‑ṭ‑ṭabiʿiyyah wa-l-ilāhiyya, ed. Māǧid Faḫrī (Beirut: Dār al-āfāq al-ǧadīdah, 1985), 119). In each case, examples from the technical field and from nature are provided. In what follows, Avicenna also uses nuṭfat al-insān as an example of a specific case in natural causation. The semen is conceived by Avicenna as an effective cause (or, if the mixture of female and male contribution is implied, as material cause as well?) which can be used as a middle term in demonstrative proofs. This is because what is becoming already exists (yūǧad al-kāʾin) with no division (lā farqa bayna l-qismayn) between cause and effect (?). For the Book of the Salvation, see Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition, 115–117.

49 See Hidemi Takahashi, “The Influence of al-Ghazālī on the Juridical, Theological and Philosophical Works of Barhebraeus,” in Islam and Rationality, ed. Georges Tamer (Leiden: Brill, 2015). For the Doctrines of the Philosophers see Ayman Shihadeh, “New Light on the Reception of al-Ghazālī’s Doctrines of the Philosophers (Maqāṣid al-Falāsifa),” in In the Age of Averroes: Arabic Philosophy in the Sixth/Twelfth Century, ed. Peter Adamson (London: Warburg Institute, 2011).

50 Al-Ġazālī, Doctrines of the Philosophers “Teaching (qawl) regarding the Human Soul” (text: al-Ġazālī, Maqāṣid al-falāsifa, ed. Sulaymān Dunyā (Cairo: Dār al-maʿārif bi-Miṣr, 1961), 370).

51 An example from a Christian-Arabic author shows that there might be further instances, where nuṭfah/nuṭptā is used for sperm drop in figurative speech in the writings of later Christian authors in an Islamic milieu: Paul of Antioch, in his Response regarding the Miracles of Christ, attributes Jesus Christ to originate “neither from intercourse (ǧamāʿ) nor from a drop (nuṭfah):” Paul of Antioch, Response regarding the Miracles of Christ (text: Louis Cheikho, ed., Vingt traités théologiques d’auteurs arabes chrétiens (IXe–XIIIe siècle) (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1920), 43; translation: Georg Graf, “Philosophisch-theologische Schriften des Paulus al-Râhib, Bischofs von Sidon: Aus dem Arabischen übersetzt,” Jahrbuch für Philosophie und spekulative Theologie 20 (1906): 55–80, 160–179, here 166). The translation by Max Horten is free and does not include an exact match for nuṭfah, cf. his “Paulus, Bischof von Sidon (XIII. Jahrhundert). Einige seiner philosophischen Abhandlungen,” Philosophisches Jahrbuch 19 (1906): 144–166, here 161.

52 Florian Jäckel, “Re-Negotiating Interconfessional Boundaries through Intertextuality: The Unborn in the Kṯābā ḏ-Huddāyē of Barhebraeus (d. 1286),” Medieval Encounters 26 (2020): 95–127, especially 103–106.