David Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, Vol. 582, Subsidia 104. Leuven: Peeters, 2000. Pp. xii + 864. Paper, € 160. ISBN 90-429-0876-9. Some Annotations on David Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, Vol. 582, Subsidia 104. Leuven: Peeters, 2000.

[1] David Wilmshurst first became interested in the Church of the East when working as an administrator in the Hong Kong Government. He completed a doctoral thesis in 1998 at Oxford University under the supervision of Sebastian Brock and published ‘a significantly expanded version’ of his thesis in the Subsidia series of the Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium (Leuven 2000). It is a book of imposing bulk, which only partially corresponds to the wide scope set out in the title: The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. What the author in facts does is to catalogue very scrupulously an impressive amount of documentary material relating to the history of the Church of the East.

[2] Chapter 1 (p. 1-15) provides the reader with general information on the book and a survey of the sources. It is remarkable how scanty the original Syriac historiography is in most of the centuries under study. After Bar Hebraeus’ Chronography and the History of Rabban Sawma and Mar Yahballaha (date of composition 1317-1319) and the additions to the Chronography in the Bodleian Ms. 52 (relating the Timurid invasion of Mesopotamia in 1394), Syriac historiography seems to fade out until the 19th century.

[3] Wilmshurst mentions here and there East-Syrian poetry composed on historical subjects (wars, famine, Kurdish assaults). It is probably among those poems written in Classical or Vernacular Syriac—few of them are published and even fewer carefully studied—that we should look for an East-Syrian perception of history from the Mongolian period to the 19th-century. Wilmshurst, however, does not appear to be interested in literature other than historical narrative as an indirect source for his reconstruction. For instance, Macuch’s Geschichte der spät- und neusyrischen Literatur (Berlin-New York, 1976) does not appear in his bibliography.

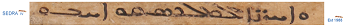

[4] The silence of (East-)Syrian historians is partly compensated for by other sources: colophons, inscriptions and—especially after the intensification of diplomatic contacts with Rome in the 16th century—the official correspondence between the Vatican and the East-Syrian Patriarchs, reports from missionaries, diaries of European travellers. Wilmshurst’s research focused on manuscript colophons, since, as the author states, ‘in many cases, the name of a priest or a deacon is the only evidence for Christian activity in a particular village’ (p. v).

[5] The author presents a fair discussion on the terminology used (p. 4). Nevertheless, expressions such as ‘schism’, ‘conversion to Catholicism’ or ‘to become a Catholic’ used for describing the facts of 1552 and their consequences might have been more accurately pondered and discussed from the juridical and historical points of view. Was it really a schism? Who called/calls it a ‘schism’? Who converted/was converted to what? What did it mean ‘to became a Catholic’ in various circumstances? The same holds for ‘traditionalist’ used to distinguish those in the Church of the East who did not accept the union with Rome. Together with its counterpart ‘non-traditionalist’ used for the Catholic Chaldeans, the term ‘traditionalist’ may be a useful label for a Western scholar, but it risks introducing an external and questionable point of view onto dangerous ground. Which side tradition takes is often a moot point.

[6] The author presents a fair discussion on the terminology used (p. 4). Nevertheless, expressions such as ‘schism’, ‘conversion to Catholicism’ or ‘to become a Catholic’ used for describing the facts of 1552 and their consequences might have been more accurately pondered and discussed from the juridical and historical points of view. Was it really a schism? Who called/calls it a ‘schism’? Who converted/was converted to what? What did it mean ‘to became a Catholic’ in various circumstances? The same holds for ‘traditionalist’ used to distinguish those in the Church of the East who did not accept the union with Rome. Together with its counterpart ‘non-traditionalist’ used for the Catholic Chaldeans, the term ‘traditionalist’ may be a useful label for a Western scholar, but it risks introducing an external and questionable point of view onto dangerous ground. Which side tradition takes is often a moot point.

[7] In Chapters 3 to 6 (p. 38-341), the author arranges the information that he has collected according to geographical criteria. The result very much resembles Fiey’s Assyrie Chrétienne (Beirut 1965-68), the corresponding paragraphs of which are quoted in square brackets beside Wilmshurst’s titles. Of each of the regions examined (Nisibis and Beth ‘Arabaye, Amid, Egypt-Syria-Palestine-Cilicia-Cypros, Mardin, Seert, Gazarta, ‘Amadiya, Berwari, ‘Aqra, Erbil, Kirkuk, Mosul, Hakkari, Urmia), the author sketches a brief ‘Ecclesiastical History’—in reality a survey of the various dioceses—and a detailed ‘Topographical Survey’ with copious information on districts, villages, monasteries etc. Wilmshurst reports in detail and organizes the data provided by more than 2500 East-Syrian colophons: number of manuscripts copied in a given place, names of scribes and genealogical reconstruction of their families, occasional historical information recorded by the copyists, ecclesiastical title of the persons mentioned in the colophons as copyist, copyist’s family or purchaser(s), etc.

[8] The evidence provided by manuscript colophons is integrated with information coming from secondary sources. Whenever available, from the 19th century onwards, demographic data (number of Christian believers or families, priests, monks, churches; distribution of the population according to ethno-linguistic or religious criteria) are presented in clear tables. The use of secondary literature, however, turned out to be a little superficial in a number of cases into which I was able to inquire.

[9] In 1654 the Belgian Carmelite Fr. Dionysius of the Crown of Thorns visited the village of Telkepe, in the Mosul plain, to visit the Patriarch Mar Ilyas. In his diplomatic discussion with the Patriarch he received help from a ‘well-disposed’ priest Joseph. Fiey (Assyrie Chrétienne 359-360) identifies this priest Joseph with a Joseph mentioned in a colophon as malpana ‘teacher, professor’, together with another priest Joseph qankaya ‘sacristan, curate’. We know, thus, of the existence of at least two priests called Joseph in Telkepe in 1654. Fiey suggests that the priest who met Fr. Dionysius was probably none other than Joseph son of Jamāl al-Dīn (‘Ce prêtre Yūsif est probablement le même que...’), author of a number of poems in Vernacular Syriac (see Macuch, Geschichte, p. 99-100). Wilmshurst presents this identification as a fact, without providing further evidence: ‘Denys [Fr. Dionysius] tried unsuccessfully to persuade him [the Patriarch] to become a Catholic, with the help of the influential Telkepe priest Joseph, son of Jamāl al-Dīn. Joseph, who composed several religious poems…’ (p. 223-224).

[10] About the famous East-Syrian author and scribe Israel of Alqosh, Wilmshurst writes: ‘He remained a traditionalist [sic!] throughout his life, remarking in 1611 that he had preserved the old faith of the Church of the East, ‘corrupted by the Jacobites’ (p. 243. quoting H.L. Murre-van den Berg, ‘A Syrian Awakening. Alqosh and Urmia as Centers of Neo-Syriac Writing’, unpublished paper). The text by Israel of Alqosh runs in fact: ‘This is the profession of the faith of the maddenhāyē (Fiey: ‘Orientaux’). We have kept it truthfully from the time of the first apostles, and grace dwelled in it, and the ya‘qubāyē (Fiey: ‘Nestoriens’) changed it’. I quote from the same paper by H.L. Murre-van den Berg, published in R. Lavenant (ed.), VII Symposium Syriacum (1996), Orientalia Christiana Analecta 256, Rome 1998, 499-515. It is difficult to find in these verses a conscious and explicit attempt to defend the ‘traditional’ faith of the Church of the East against the Catholic sympathies of others, unless we read a text such as that translated by Fiey, where ‘Jacobites’ (attested in all manuscripts available to me) was mysteriously or, better, ideologically replaced by ‘Nestorians’. Pace Wilmshurst (and Murre-van den Berg), Israel of Alqosh or whoever wrote those lines probably had no Catholics in mind at that moment.

[11] Chapter 7 (p. 342-370) is an attempt to summarize and arrange chronologically the material that in the previous chapters is presented geographically, region by region, district by district, village by village. Important issues come to the fore in this chapter:

- the situation in the outlying provinces of the Church of the East (Persia, Central Asia, India, China) which, ‘with the important exception of India, collapsed during the second half of the fourteenth century’ possibly because of ‘a combination of persecution, disease, and isolation’ (p. 345);

- the patriarchal succession, which is not documented by reliable evidence in the period 1318-1552, while from 1552 to the 19th century it is certain in the case of the Mosul patriarchate, but less exact for the successors of the rebellious Sulaqa;

- the population of the Church of the East (clergy and believers) throughout the centuries, with comparative statistics of the faithful to the Chaldean and Qudshanis Patriarchates in the last period relevant for the study (p. 363): ‘With a membership of around 100,000 in 1913, the Chaldean church was only slightly smaller than the Qūdshānīs patriarchate (probably 120,000 East Syrians at most, including the population of the nominally Russian Orthodox villages in the Ūrmī region)’;

- an attempt at comparison of ‘the resources and influence of the Mosul, Qūdshānīs and Āmid patriarchates at different periods’ (p. 343).

[12] In 4 appendixes, David Wilmshurst provides the reader with the corpora used as evidence in his study. Appendix One (p. 371-377) contains ‘a concordance of manuscript catalogue numbers’. The concordances provided includes manuscript catalogues from ‘Aqra, Alqosh, Mosul, Telkepe, and Dohuk. Appendix Two (p. 378-732) is ‘a list of East-Syrian manuscript colophons and inscriptions’. The 2450 records are listed in chronological order from 615 to 1984 A.D. and arranged in five columns giving: catalogue number, date, place where the manuscript was copied, name of scribe(s), and other details useful as historical information. From the point of view of a Syriac scholar, possibly not of a historian, it is regrettable that no reference is made to the contents of the manuscripts. Appendix Three (p. 733-738) contains ‘extracts from the correspondence of the East-Syrian patriarchs’ in the Italian or Latin translation preserved in Rome and published by Giamil (Rome 1902) and Assemani (Rome 1719-1728). Appendix Four (p. 739-746) contains a brief biography (4-9 lines) of 41 Chaldean bishops of the 19th century.

[13] The bibliography (p. 747-757) is divided into three sections: books, articles, manuscript collections and notes on manuscripts and inscriptions. In the third section of the bibliography (and in the study), manuscript collections containing texts in Vernacular Syriac (M. Lidzbarski, Die neu-aramäischen Handschriften der Kgl. Bibliothek zu Berlin, 2 vol., Weimar 1896 and Y. Habbi, “Udabā’ al-sūrith al-awā’il”, Majallat al-majma‘ al-‘ilmī al-‘irāqī al-hay’a al-suryānīya 4 (1978) 97-120) have not been included.

[14] The work is complete with maps of the territories covered by the study. ‘The details given in these maps have been taken from the 1921 British G.S.G.S. map series ..., revised from an earlier I.D.W.O. map series of 1916, which has recently been used as the basis for an atlas of East Syrian settlement in Kurdistan [J.C.J. Sanders, Assyro-chaldese christenen in oost-Turkije en Iran. Hun laatste vaderland opnieuw in kaart gebracht, A.A. Brediusstichting, Hernen 1997]’ (p. 8).

[15] The quantity of material that the author has analyzed is immense. The amount of information he has managed to include in 370 pages of discussion, 51 tables, 4 genealogical trees, 5 concordance tables of manuscript catalogues, 350 pages of data-base on manuscript colophons and inscriptions, 2 indexes (of places, p. 758-795 and proper names, p. 796-845), and 7 excellent maps is really impressive. This book will certainly become an indispensable research tool for students of the Church of the East and Syriac scholars.

[16] Two important East Syriac works by ‘Abdisho‘ bar Brikha (Kunasha d-qanone sunhadiqaye—ed. by A. Mai, Rome 1838—and Tukkās dine 'edtanaye, composed respectively in 1284 and 1315-1316) do not appear among the sources used by Wilmshurst. Their content is canonical and provides a picture of the ecclesiastical structure of the Church of the East at the beginning of the 14th century.

[17] The facts of 1552, which eventually led to the East-Syrian Uniate movement, represent an important change in the history of the Church of the East. In this connection, it would have been worth mentioning the fact that the primatus Petri was a canonical principle fairly well established in the East-Syrian milieu a couple of centuries before Sulaqa’s rebellion. ‘Abdisho‘ bar Brikha, e.g., attributes the shultanutha over all the patriarchs to the successor of Peter, the bishop of Rome (Kunasha d-qanone sunhadiqaye—ed. by A. Mai, Scriptorum veterum nova et inedita collectio X, Rome 1838, 327, 165). The patriarch Mar Yahballaha III addressed the Pope in similar terms in an Arabic letter dated 1304 (L. Bottini, ‘Due lettere inedite del patriarca Mar Yahballaha III (1281-1317)’, Rivista degli studi orientali 1992, 239-256).

[18] In Chapter 2, some statements about the history of the 14th century need to be corrected or at least toned down. When the author comments upon the diplomatic mission of Rabban Sawma (1287-1288, not 1284-1285 as stated on p. 17) and says that ‘the Church of the East worked... to encourage a Mongol-Christian alliance against the Mamluk’ (p. 16-17), he is probably going too far. As far as we know, there is no evidence to support such an interpretation. The role of ecclesiastical ‘ambassadors’ sent by the Ilkhans was not a consequence of a specific interest of the Church in political and military alliance, and their position was subordinated to that of other ambassadors—Western, mainly Genoese, guests at the Ilkhanid court—who were sent with them. Of course, the History of Rabban Sawma and Mar Yahballaha might give us a different impression, due to the origin and character of the narrative. But it should not be forgotten that, even though Rabban Sawma’s mission is ‘the best known Mongol initiative towards the Christian powers’ (p. 17), it was only one of many and not necessarily the most successful.

[19] The hypothesis that the synod of 1318 had to cope with the corruption and illiteracy of the clergy ‘perhaps because Yahballaaha III, who knew little Syriac himself, had been unable to control his bishops and visitors effectively’ (p. 18) does not appear to be based on solid grounds. It was precisely during the partiarchate of Mar Yahballaha III that ‘Abdisho‘ bar Brikha wrote his canonical works, which may bear witness to the patriarch’s interest in setting up an ‘up-dated’ set of rules for the Church of the East, although he personally was not a scholar, an exegete, or a canonist as his predecessors and successor were. Wilmshurst refers to probable difficulties in the relationship between Mar Yahballaha and (some of) his bishops. This conjecture is in fact supported by evidence provided by Ricoldo da Montecroce, who attended a debate in Baghdad between Mar Yahballaha and some bishops about the permission to preach that the patriarch had given to the Latin missionaries (Riccold de Monte Croce, Pérégrination en Terre Sainte et au Proche Orient. Texte latin et traduction, Lettres sur la chute de Saint-Jean d’Acre. Traduction par R. Kappler, Paris 1997, 152-155).

[20] The ‘humane emir Choban’ had much more than ‘an important moderating influence on the il-khan Abu Said’. Choban was in fact the real ruler at the beginning of the reign of Abu Said, who came to the throne as a boy. Indeed Amir Choban was a Muslim, and the good will he showed to the Christians according to the History of Rabban Sawma and Mar Yahballaha may have sprung more from political calculation than from ‘humane’ disposition.

[21] Finally, the note about the Ms. Vat. Syr 622 (p. 390) needs correction: the princess Sara was not the daughter, but the sister of Giwargis, king of the Önggüd (autoptical check in Rome, 21-06-2002).