Generous Devotion: Women in the Church of the East between 1550 and 1850

In the centuries following the Ottoman conquest of northern Mesopotamia and Kurdistan, the Church of the East showed a remarkable vitality, which was expressed among other things in a considerable manuscript production and the restoration of churches and monasteries. This article intends to highlight the contribution of women to this revival. It is based mainly on a study of manuscript colophons and a few inscriptions, which testify to the large number of women who were involved in financing the production of manuscripts and to their reasons for doing so. A closer reading of the colophons also reveals details about the social position of these women, the role of their fathers, brothers, and husbands, as well as about their position within the church—varying from incidental references to daughters of the convenant, deaconnesses and nuns, to highly-esteemed mothers and well-doers in the Christian community. Finally, the article asks for a closer reading of the colophons in order to enlarge our knowledge of the Church of the East in this period of history.

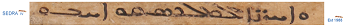

[1] In the early summer of 1707, the priest Yosep, son of the priest Giwargis, son of the priest Israel Alqoshaya from the Shikwana family, one of the famous scribes’ families of Alqosh of the period, in his hometown finished writing a taksā d-kāhnē, a priests’ office book which included the regular Sunday eucharistic liturgies, a few special liturgies and a number of huttāmē by various authors. In his colophon he notes: “This book of the taksā d-kāhnē was written thanks to the money and labor of Belgan, a believing woman from Alqoshta, and she bestowed it upon the holy church of Mar Yohannan in the blessed village of Dawedaya, in the region of Sapna (Amadiah region). From now on, everyone is required to read from it.”1

[2] Belgan from Alqoshta (a little village in the mountains of Berwari, about 65 miles north of Alqosh in what is now southeastern Turkey) is not the only woman of the Church of the East who makes her appearance in the Syriac manuscript colophons of the Ottoman period. In David Wilmshurst’s list of colophons and inscriptions, more than eighty women are mentioned in sixty-six entries made between 1500 and 1830.2 On the total number of colophons and inscriptions of this period, numbering about 1350, this already constitutes a significant group of about six percent, but when compared with the number of colophons that mention commissioners and sponsors (the roles in which women occur most frequently), the percentage goes up to about eighteen percent.3 Although most of the colophons are edited only partially, the information available in the catalogues already provides us with a wealth of information on the women of the Church of the East in this period. It is this information that is used for the present contribution.4

[3] The period of about 1500 to 1830 is the period in which the Church of the East, after a century of almost complete silence following Timur Leng’s raids in the late fourteenth century, slowly recovered from the destruction and ravages wrought by the plague. The great majority of the East-Syriac manuscripts that have survived to our day date from this period, in which apparently a great effort was made to restore the classical heritage. Especially between 1670 and 1760 the large village of Alqosh was the center of an enormous manuscript production. Its scribes provided new manuscripts for village churches and monasteries in northern Mesopotamia and northwestern Iran that in this period were also often restored. Three famous families dominated life in this village: the Shikwana and Nasro families, to which most of the scribes belonged, and the Abuna family, from which metropolitans and patriarchs were selected.5 The patriarchs had their official see in the famous monastery of Rabban Hormizd, not far from Alqosh, and so added to the importance of the region. The importance of the Alqosh region (including the monastery of Rabban Hormizd and the village of Telkepe) is also reflected in the colophons of the manuscripts in my list: thirty-five of the fifty-eight manuscripts were produced here. Smaller centers of manuscript production were found in villages and monasteries in the west (Amida, Gazarta), in the Hakkari mountains (Gissa) and western Iran (Darband, Tergawar). In addition to the copying of older texts, this period also saw a limited production of new texts, both in Classical Syriac and in Modern Aramaic, the spoken language of the majroity of the members of the Church of the East.6

[4] Politically, the region became more and more part of the Ottoman Empire, although it took until the middle of the nineteenth century before the Ottomans were able to exercise any kind of effective control over the Hakkari Mountains with its independent Kurdish and Assyrian tribes. Roman Catholicism also made its influence felt in the region. In 1552, Yuhannan Sulaqa established official links with the papacy and in doing so created the uniate counter-patriarchate in 1553. Although his successors severed links with the papacy towards the end of the sixteenth century and continued as the Church of the East patriarchate of Qodshanis, both this line (whose patriarchs took the formal name Shimcun) and the line of Rabban Hormizd (whose patriarchs took the formal name Eliya) had occasional contacts with Roman Catholic missionaries. In 1681, a new Catholic patriarchate (whose holders took the name of Yosep) was created in Amida (Diyarbakır), under the influence of Capuchin missionaries. In 1830, this patriarchate merged with the by then Catholic patriarchate of Alqosh.7

[5] Despite occasional setbacks caused by wars (between Turkey and Persia as well as between local rulers), outbreaks of the plague and looting by local robbers or rival tribes, the considerable manuscript production and the restoration of churches testify to the vitality of the Church of the East in the Ottoman period. However, so far hardly any attention has been paid to the role of women in this ‘awakening’. This study focuses on the question to what extent and in what way women participated in it. The following themes will be discussed: the position of these women within their families [6-8]; the geographical origin of the women and the manuscripts [9-10]; their names [11], money and status [12-13]; and the reasons for commissioning, sponsoring8 and donating9 [14-16]. I will end with a few concluding remarks [17-18].

[6] There can be little doubt that the women in the colophons are first and foremost identified by their family relationships. The most common way to introduce a woman is to add her father’s name to her own: Kanzadeh, daughter of the deacon Sulaiman (c. 1660, no. 14), Gozal, daughter of the smith Hanna of Mosul (1707, no. 31), Shmuni, daughter of the priest Hoshaba (1722, no. 37), and many more. In the one case of a female scribe, an extended genealogy is given, extending to five generations: Teresa, daughter of the priest Khadjodor, son of the deacon cAbdelkarim, son of the priest Bakos, son of the priest Khadjo, son of the priest Bet Sabrishoc of cAyn Tannur (1767, no. 53). This usage is exactly parallel to that regarding the men in the colophons: a brief genealogy (usually only the father) in the case of donors, sponsors and commissioners, long genealogies in case of scribes. In one case, a woman is identified by giving the name of her mother only: Naze, daughter of Shmuni (1766, no. 52), whereas one woman is identified first by her mother, than by her husband: Maryam, daughter of Elisabeth and wife of Maroge, of Nisibis (1586, no. 7).10 In addition, in quite a few cases a mother and daughter sponsored or commissioned together, for instance Shona, daughter of Oshacna and her mother Nasrat (1706, no. 29), Hatun and her mother Sette, daughter of the priest Eliya of Telkepe (1710, no. 32), as well as cAzize and her mother Baghdad, together with their father and husband Isaac, son of Giwargis (1705, no. 28).

[7] In this list, the second most important way of identifying a woman is by giving her husband’s name. However, of only twenty-one of the eighty-four women in the list a husband is mentioned, often in addition to the father, e.g. in the case of a manuscript donated by a couple such as Auraham, son of Mako, and his wife Shmuni, daughter of the priest Quriaqos (1682, no. 19), or by two couples together: “the money was given by the believers Hanne, Kammo, and their righteous wives Sara and Maryam” (1723, no. 38). An eighteenth-century inscription in the church of Mar Quriaqos in Salmas simply says: “This church was renovated by the wife of Amr, may the Lord give her rest” (18th c., no. 36). In addition to these twenty-one cases where a woman’s husband is explicitly mentioned, in eleven instances marriage can be inferred from the mentioning of a dowry, (grand)sons or daughters. The two instances of dowry (māhrā) probably both date to the early eighteenth century. In the first case the manuscript itself constitutes the dowry, taken for the daughter of the priest cAbdishoc son of Zangish (no. 23), in the second, the manuscript contains a note of a dowry taken by the priest Hanna for his daughter (no. 24). Both women remain anonymous.11

[8] A total of thirty-two married women among the more than eighty women in the list is a strikingly low number, which requires an exploration of the possible reasons. The most obvious one, although explaining only a minority of the cases, is that women remained unmarried for religious reasons. In five instances, there is little doubt: women are referred to as a nun (rāhiba, Maryam, daughter of priest Hormizd of 1542, no. 2, and Hatun in Mar Yohannan Nahlaya, 1629, no. 12), as a daughter of the covenant (ba(r)t qyāmā, Seltana, daughter of Belgana, c. 1600, no. 8), as a deaconess of the monastery of Mar Augin (mshammshānītā, Maryam, 1739, no. 45) and as a distinguished virgin (btultā zāhyā, Shmuni, daughter of Marqos, 1824, no. 63).12 In a number of other cases one may perhaps assume that the women were not married yet, as in the case of the first colophon in our list, in a manuscript copied by a priest Aprem son of the priest Yacqub for “his own and learned daughters Tamar and Shmuni” (1521, no. 1), or our female copyist, the girl Teresa, daughter of the priest Khadjador, who was fifteen years old when she wrote her manuscript in 1767 (no. 53).13 In this respect, one also wonders to what extent the custom described by Surma d’Bait Mar Shimun (a member of the patriarchal family of Qodshanis) in the early twentieth century might explain the fact that for some women no husband is mentioned. She notes: “Often girls and youths live as virgins in their parents’ house. They are called Rabbanyati [the usual title for nuns, MvdB] although they have not received the blessing of the Bishop, so they are not officially recognized.”14 With perhaps a number of widows among them, it seems not unreasonable to assume that a significant part of the remaining fifty-two women were not married. In addition, there is the distinct possibility that even if a woman was married, it was not always necessary to mention that fact in the colophon, especially if the husband had not been personally involved in the commissioning or sponsoring. Whatever the reasons for the low number of husbands in the colophons, it seems to me that at the very least this indicates that husbands in the majority of cases were not the defining factor in deciding whether women could or would donate valuables or commission and sponsor the writing of a manuscript.

[9] It is worthwhile to take a closer look at the place names mentioned in these colophons. The dominance of Alqosh as a center of manuscript production has been mentioned above, but for a study of the involvement of the women, the location of the monasteries and churches benefiting from their generosity seems to be more important. Surprisingly enough, it is usually only the church and its location, rather than the hometown or village of the commissioner or sponsor, that is mentioned in the colophon. It seems to me that the reader of the colophon is meant to understand that the commissioner or sponsor lived in the vicinity of that particular church. One of the few colophons to mention the woman’s home village, is the one naming Belgan from the village of Alqoshta (no. 30), who bestowed a manuscript to a church in Dawedaya, a village about fifteen miles south.

[10] When we look up the churches and monasteries that profited from the generosity of the women of the Church of the East on a map, we find that most of these are situated in a rather circumscribed area: a small band stretching northwards from Mosul, via Telkepe, Alqosh, and Dohuk towards Dawedaya, and a little eastwards from there, towards Aqra, via Tella, Artun, Geppa and Barzane.15 Regions that benefited to a lesser extent were the monasteries around Mardin, Nisibis, Seert and Gazarta in the west. The Hakkari mountains and the Persian territories of the country of the Church of the East are represented only by the inscriptions of Salmas,16 and by the reference to the place of origin of a few women.17 Although a comparison with the larger collection of colophons will perhaps refine this picture somewhat, these data suggest that in the southern and western regions the Christians were wealthier and church life was more active. It was not only churches and monasteries close to home that benefited: the Church-of-the-East community in Jerusalem and particularly the monastery of Mart Maryam also shared in the relative prosperity, which confirms the importance of this city in the spiritual life of the time.18

[11] Of the seventy-five woman’s names in the colophons, only about twenty-six can be considered traditional Syriac names. Most of these are biblical and one is Greek. These twenty-six women, however, share among them only nine different names, of which the most popular are Shmuni and Maryam (eight times each), and Helen (five times).19 All other names will probably be identified as Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish and perhaps a few as more recent Aramaic/Syriac names, but much further research is required here. Note also here the interesting case of two women named after illustrious cities: Baghdad (1705, no. 28) and Stambul (1773, no. 55), a custom that may be observed also among present-day Christians from the region who name their daughters, e.g., after the city of Edessa.20

[12] The most interesting aspect of these colophons is the fact that they show that at least some women of this period had the independent use of money or other possessions. Twenty-three women in this list are mentioned as the single donor or commissioner of a manuscript, whereas seven more are listed as having donated other valuables such as land or buildings. Some examples of individual commissioning are Belgan from Alqoshta, mentioned above (no. 30), Putta, daughter of chief cAtallah of Harab Olma (ca. 1550, no. 3), Shmuni, daughter of Nacazar (1701, no. 25) and Alpo (1808, no. 58). Thirty-one women donated land or commissioned manuscripts together with others: their husbands, mothers, other women or other men. The deacon Bako and his wife Rihana commissioned a gazza together (1686, no. 20), while the two couples Hanne and Sara and Kammo and Maryam (1723, no. 38) provided the money for a manuscript. In 1706, Shona and her mother Nasrat commissioned a Gospel lectionary (no. 29), while in 1744, Amat, her daughter Maryam, Helen, Teka, and Elfiya together paid for a manuscript that was commissioned by the priest cAbdishoc from Telkepe (no. 48).21 Some women made individual donations in other ways: around 1613, Shazemana, the wife of Yazdan, donated a “silver cup worth a hundred drachmas” and “a house in Sharukhiya” to the church of Mar Pethion in Amida (Diarbakir, no. 9), whereas Kanzadeh, daughter of the deacon Sulaiman, ransomed a gazza that was looted from the church of Mar Yareth in Barbitha and donated it to the church of Mar Shemcon, Mar Giwargis and Ma(r)t Meskinta in Mosul (around 1660, no. 14). So far no concrete indications of the price of manuscripts as compared with other goods have been found, and only in a few instances prices are mentioned, in a variety of different currencies.22

[13] Whereas it seems reasonable to assume that the sums involved were quite considerable, especially when women were paying and commissioning on their own, there is another indication that many of the women in this list did not come from the lower strata of the Church-of-the-East communities of the time. Although in a considerable number of cases futher details about their fathers are lacking, a large number of women appear to come from the more important families; many of the fathers are priests, and a few are chiefs.23 Among the husbands, hardly any priests are mentioned; the large majority of them come without title.24 Not surprisingly, in the few cases when other family members are mentioned (sons, brothers) the number of priests or even a patriarch, like the Lady Azdiah, mother of Mar Eliya (1738, no. 44) is relatively high.25 The last case also indicates that it is possible that a father or a husband was a priest but was not referred to as such in the colophon. We know from other sources that Azdiah’s husband, Hoshaba son of Giwargis was indeed a priest, although the colophon makes no mention of it.26 Although we do not have much to go by to compare the numbers of priests and chiefs with the total numbers of men, it is unlikely that these would constitute more than fifty percent of the male population. It seems safe, therefore, to assume that women from priestly and other types of leading families were more likely to have some money available and to be involved in manuscript production.

[14] The final question to be asked is what was the most likely reason for these women to spend money on manuscripts or church buildings. Although there is little hard evidence, it seems possible that some of these women wanted to possess manuscripts for private use within their families or (religious) community. The one example of a female scribe, Teresa, daughter of the priest Khadjador (1767, no. 53), is the most convincing proof that at least some women were able to read, and it is likely that she copied the works of John of Damascus for her own education. I am inclined to assume that the already mentioned “learned girls Tamar and Shmuni”, were able to read the miscellaneous work that their father for copied for them, including the ‘Discourse on the monk Mar Shamli’ and the ‘Book of the Centuries’ (1521, no. 1). The same might be assumed of the deaconess Maryam, living in the monastery of Mar Augin, who ordered a ‘Life of Mar Augin’ (1739, no. 45).27 Another book that was commissioned for private use was the ‘Hexaemeron’ of Rabban Emmanuel (ktābā d-shettat yāumē), which the daughter of cAbdishoc of Alqosh ordered “for her brother the priest Yohanna, to read from it” (1701, no. 26). Perhaps also for use within the family was the ktābā d-hermē d-natturē (‘book of charms of protection’), which was ordered by cIsa and Sanam in 1770 (no. 54).28

[15] In all other cases we may virtually rule out the possibility that manuscripts were commissioned for private use. In fact, it seems unlikely that these women (as most of the lay men) were able to read at all, since reading skills in general seem to have been restricted to the deacons and priests.29 The colophons, however, provide us with two important hints as to the reason for commissioning and sponsoring. The first is that the majority of the manuscripts are said to have been copied ‘for’ a particular church or monastery. That is, if a commissioner, sponsor or donor is mentioned, a particular location for the manuscripts is usually also given, as in the very first example I quoted – Belgan bestowing a manuscript on the church of Mar Yohannan in the village of Dawedaya. The large number of such references indicates that this was indeed the most important reason for women to commission a manuscript.30 This is also confirmed by the contents of these manuscripts. The large majority of these are of a liturgical nature and belonged to the essentials of every village church: the lectionaries (the Psalter, Gospel lectionary, Epistle lectionary, and the ktābā qeryānē mparrshē, i.e. OT and other NT readings),31 the taksā d-kahnē or the taksē d-quddāshā (the liturgies of Addai and Mari, Theodore and Nestorius), and the other office books, the ktābā d-hudrā (office book with hymns and other variable parts of the liturgy for all Sundays and feast days of the year), the ktābā d-gazzā (later additions to the hudrā), the kashkol (extract from the hudrā),32 the ktābā d- c unyātā,33 and the liturgies for funerals and the Rogation of the Ninevites.34 Among the books dedicated to churches, there are few non-liturgical works.35 Despite the fact that a further interpretation of the selection of books that were commissioned and donated is still awaiting a study of the larger context of manuscript commissioning in this period, there can be little doubt that the prime purpose of sponsoring the production of manuscripts was to enlarge the number of liturgical books in the churches and monasteries of the region, thereby contributing to the rebuilding of church life in the Ottoman period. The Gospel lectionary and the office books of the hudrā and gazzā were the most popular contributions, presumably because these were considered the most important books of the regular Sunday liturgy.

[16] I assume, therefore, that it is first and foremost religious devotion that inspired these generous donations made by the women of the colophons. These women, like the men that were involved in the commissioning and production of the manuscripts, must have believed that such material support to the life of the church constituted an essential act of piety, which would benefit them here and in eternal life. One of the few colophons to give us some information on this subject36 is the one about Kanzadeh who redeemed a manuscript from robbers (around 1660, no. 14). Of her the scribe says: “May Christ our Lord and God give her reward and repay her hundred to one, and let her inheritance be with Martha and Maryam and with all the companions of the virgins and the just and righteous women, Amen.”37 A similar phrase refers to Alpo in 1808: “may Christ give her an inheritance with Sara, I say, Ripqa and Rachel […] and with all the holy righteous women, Amen.” (no. 59).38 In at least two cases, the donation is given in connection with a deceased person: the first by Dormlik, daughter of Harun of Nisibis, who donated a Gospel lectionary to the church of Mar Yacqub in Nisibis “on behalf of her late husband Darwish” (1569, no. 5), the second in a manuscript that was commissioned by Hanna, son of cAbd Allah, his wife Hane, daughter of Maqsud, and their relatives Kanun, cIsa, Jemca, and Hormizd, to commemorate the death of Hanna and Hane’s son cAbd al-Masih on 25 August 1726, for the church of Mart Maryam in Karamlish (1727, no. 40). It is likely that such donations were supposed to secure peace after death for the deceased, as one might also from two inscriptions in which the phrase “may the Lord give her rest” occurs.39 Apart from the spiritual benefits centering on the expectation of blissful life after death, it seems likely that immediate social benefits also resulted from generous contributions to the life of the church. The mere fact that these acts of piety were recorded in the manuscripts or on the church walls indicates that public knowledge and recognition of these gifts constituted an essential part of the economy of giving.

[17] The above overview of some of the most salient features of women’s presence in the literary remains of the years between 1500 and 1830 indicates that women, especially those from the more influential and literate families, took an active part in the religious life of the era. Not only did a significant number of them choose to live a celibate, religious life, and do we know of a few that were able to read and contribute to the religious literature of the time, many others contributed to the reawakening of the life of the church by paying for repairs of churches and monasteries, by donating money or land to the church, and, most importantly, by commissioning and sponsoring liturgical manuscripts that were essential to the worship-life of the church of this region. In this way they not only sought to secure religious benefits for themselves or their kin, they also confirmed the importance of their role in the community as a whole.40

[18] The study of the colophons raises one more important issue, that of the literary genre of the colophons themselves. The colophons constitute the largest body of Classical Syriac texts of this period,41 but so far they have been studied and edited mainly from a strictly historical point of view: what names, dates and incidents are referred to. The literary genre of the colophons with its flowery language of praise and humility, as well as the colophons’ possible function in the social and ecclesiastical structures of the times have hardly been considered worthy of separate attention. It seems to me that a verbatim edition of the colophons would help us to expand our knowledge of the period considerably, not only in the field of Classical Syriac linguistics and literary forms, but also in the field of the religious life of the Church of the East.

Appendix: Women in the colophons of the Church of the East between 1500 and 1830The list is set up as follows:

| (No.) | date |

name of the woman [pg no. Wilmshurst]

|

| (1) | 1521 |

Tamar and Shmuni, daughters of the

priest Ephrem (Aprem), son of the priest

Yaʿqub [97]

|

| (2) | 1542 |

Maryam, nun, daughter of the priest

Hormizd, son of Sulaiman [259]

|

| (3) | 1550 ca. |

Putta, sister of the priest Daniel,

daughter of chief ʿAttallah of Harab Olma

[404]

|

| (4) | 1559 |

Maryam, daughter of Mima, of Erbil

[260]

|

| (5) | 1569 |

Dormlik, daughter of Harun of Nisibis,

wife of the late Darwish [44]

|

| (6) | pre-1581 |

anonymous woman, buying East Syrian

hospice in Jerusalem [69]

|

| (7) | 1586 |

Maryam, daughter of

Elisabeth and wife of Maroge, of Nisibis

[77]

|

| (8) | 1593 ca. |

Seltana, ba(r)t

qyāmā

, daughter of Belgana from

Bet Megali (Gazarta) [71, 124]

|

| (9) | 1613 ca. |

Shazemana, wife of Yazdan [60]

|

| (10) | 1624 |

Lady Ahlijan, wife of Aspania son of

Yannan, daughter of Nahma, son of Hanna, brother of Mar Eliya bar Tappe

[96]

|

| (11) | 1624 |

Maani Gioerida of Mardin [185]

|

| (12) | 1629 |

Hatun, nun

(‘religieuse’) in Mar Yohannan Nahlaya

[92]

|

| (13) | 1631 |

Lady Naze (or: Nazekhatun), daughter of

the glorious Aumig of Salmas and wife of

Masʿud, son of Denha [327]

|

| (14) | 1660 ca. |

Kanzadeh, daughter of the deacon

Sulaiman [466, 216]

|

| (15) | 1667 |

Asmar, daughter of

Nasimo and Haushep, mother of the scribe

ʿAbdishoʿ, who is

married to Naubar [441]

|

| (16) | 1671 |

Maryam, mother of the priest and chief

David of Barbitha [118]

|

| (17) | 1671 |

Maryam, believer [120]

|

| (18) | 1681 |

Kuli, wife of the deacon Abraham, son of

superior Hormizd [234]

|

| (19) | 1682 |

Shmuni, daughter of the priest Quriaqos,

wife of Abraham, son of Mako [224]

|

| (20) | 1686 |

Rihana, wife of the deacon Bako

[224]

|

| (21) | 1690 |

Elfiya, mother of chief Kina [238]

|

| (22) | 1697 |

Zize, a believing woman from Alqosh

[143]

|

| (23) | 1700 ca. |

anonymous daughter of the priest

ʿAbdishoʿ son of

Zangish [300]

|

| (24) | 1700 ca. |

anonymous daughter of the priest

Hanna of Shah [119]

|

| (25) | 1701 |

Shmuni, daughter of

Naʿazar [146]

|

| (26) | 1701 |

anonymous lady, daughter of

ʿAbdishoʿ

Alqoshaya, sister of the priest Yohanna [251]

|

| (27) | 1704 |

Gozal, mother of the copyist the deacon

Giwargis [472]

|

| (28) | 1705 |

ʿAzize, daughter of,

and Baghdad, wife of Isaac son of

Giwargis [143]

|

| (29) | 1706 |

Shona, daughter of

Oshaʿna and Nasrat

[164]

|

| (30) | 1707 |

Belgan from Alqoshta (Berwari)

[139]

|

| (31) | 1707 |

Gozal, daughter of the smith

Hanna of Mosul [222]

|

| (32) | 1710 |

Hatun and her

mother Sette, daughter of the priest

Eliya, of Telkepe [222]

|

| (33) | 1710 |

Eddne (Ezdne), daughter of the priest

Maroge [262]

|

| (34) |

Shmuni, daughter of the chief and the

deacon Gabriel of Semmer, wife of Safar, and her

mother-in-law Dalle [141]

|

|

| (35) | 1718 |

Hazmi, daughter

of the priest Hoshaba, and her

daughter Dalle, daughter of the priest

Israel [246, 262]

|

| (36) | 18th ca. |

anonymous wife of Amr [326-7, 488]

|

| (37) | 1722 |

Shmuni, daughter of the priest

Hoshaba (of the Abuna Family)

[250]

|

| (38) | 1723 |

Sara and Maryam, wives

of Hanne en Kammo [160-1]

|

| (39) | 1723 |

anonymous women from Urmi region

[313]

|

| (40) | 1727 |

Hane, daughter of

Maqsud, wife of

ʿAbd Allah, mother of

ʿAbd al-Masih

[219]

|

| (41) | 1731 |

Helen, daughter of Nisan [146]

|

| (42) | 1732 |

Helen, daughter of

ʿArbo [239]

|

| (43) | 1735 |

Lady Shahmalak, daughter of Habash [235]

|

| (44) | 1738 |

Lady Azdiya, daughter of Safar, married

to Hoshaba son of Giwargis, mother

of patriarch Mar Eliya [250, 262, 507]

|

| (45) | 1739 |

Maryam, the deaconess

(mshammshanita) of the monastery of Mar Augin,

Nisibis [47]

|

| (46) | 1740 |

Merot, daughter of the priest Hormizd

[161]

|

| (47) | 1740 |

Shahzo, daughter of

Jemʿa [143]

|

| (48) | 1744 |

Amat, her daughter

Maryam, Helen,

Teka, and Elfiya, the

believing women [222]

|

| (49) | 1745 |

Helen, daughter of the deacon Kazum

[232]

|

| (50) | 1751 |

Maryam, daughter of the priest David

[226]

|

| (51) | 1755 |

Kandi, daughter of the priest Yalda

[518]

|

| (52) | 1766 |

Naze, daughter of

Shmuni [162]

|

| (53) | 1767 |

Teresa, daughter of the priest

Khadjador, son of the deacon

ʿAbdelkarim, son of the priest Bakos,

son of the priest Khadjo, son of the priest Bet

Sabrishoʿ of ʿAyn

Tannur, fifteen years old [61]

|

| (54) | 1770 |

Sanam, mother of

ʿIsa, of

Daralik [523]

|

| (55) | 1773 |

Lady Stambul and her daughter

Anisa [215]

|

| (56) | 1774 |

Elfiya, daughter of Yagmur [226]

|

| (57) | 1777 |

Qudsiya Hormez, grandmother of Giwargis

son of Zahor [215]

|

| (58) | 1778 |

believing ladies of Telkepe [222]

|

| (59) | 1808 |

Alpo, probably from Hassan [119]

|

| (60) | 1809 |

Marta, daughter of Haye [139]

|

| (61) | 1809 |

Bane, daughter of the priest Sabro and

sister of the priest Giwargis, from the Tiari village of

Darosh (Dadosh) [292]

|

| (62) | 1813 |

Daris Sargis and

Banusheh (vocalization uncertain)

[338]

|

| (63) | 1820 |

Helen, daughter of Yonan [141]

|

| (64) | 1824 |

Shmuni, nun, daughter of Marqos, of the

Kubyar family [555]

|

| (65) | 1826 |

Gozal, daughter of Kafo of Bidwil

[146]

|

| (66) | 1850 ca. |

Shmuni, daughter of Hormizd

Denha, of Artun [163, 578]

|

Assemani, S.E. and J.S. Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae codicum manuscriptorum catalogus, vol. ii. Rome: 1758.

Sanjian K. Avedis Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480. A Source for Middle Eastern History. Harvard Armenian Texts and Studies 2. Cambridge (Mass): Harvard University Press, 1969.

G. P. Badger The Nestorians and their Rituals. London: Joseph Masters, 1852, vol. ii.

Bello, S. La congregation de S. Hormisdas et l’église chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle. OCA 122. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1939.

Brock, S.P. “The Syriac Manuscripts in the National Library, Athens.” In Le Muséon 79 (1966), 165-85.

Chabot, J.B. “Notice sur les manuscrits syriaques conservés dans la bibliothèque du patriarcat grec orthodoxe de Jerusalem.” In Journal Asiatique 3 (1894), 92-134.

Chevalier, M. Montagnards chrétiens du Hakkâri et du Kurdistan septentrional. Publications du Département de Géographie de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne no. 13. Paris: 1985.

Duval, R. “Inscriptions syriaques de Salamas en Perse.” In Journal Asiatique 8/5 (1885): 39-62.

Fiey, J.M. Mossoul chrétienne. Essai sur l'histoire, l’archéologie et l’état actuel des monument chrétiens de la ville de Mossoul. Recherches publiées sous la direction de l’Institut de lettres Orientales de Beyrouth 12. Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique Beirouth, 1959.

Fiey, J.M. Assyrie chrétienne. Contribution à l'étude de l'histoire et de la géographie ecclésistiques et monastiques du nord de l'Iraq. Recherches publiées sous la direction de l’Institut de lettres Orientales de Beyrouth 22, 23, 42. Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique Beirouth, 1965-1986, 3 vols.

Fiey, J.M. “Sanctuaires et villages syriaques orientaux de la vallée de Sapna.” In Le Muséon 102 (1989), 43-67.

Giamil, S. Genuinae Relationes inter Sedem Apostolicum et Assyriorum Orientalium seu Chaldaeorum Ecclesiam. Rome: 1902.

Habbi, J. “Manuscripts of Talkaif Church.” In Haddad, Fahāris al-makhtūtāt, 21-50.

Haddad, P. (e.a.) Fahāris al-makhtūtāt al Suryānīya fī’l cIrāq (‘Catalogues of Syriac Manuscripts in Iraq), 2 vols. Baghdad: Syriac Academy, 1977-1981.

Haddad, P., and Isaac, J. Al-Makhtūtāt al-Suryānīyā wa’-l-cArabīyā fī khizānat al-rahbānīya al Kaldānīya fī Baghdad (‘Syriac and Arabic Manuscripts in the Library of the Chaldean Monastery, Baghdad’), Bagdad: Iraqi Academy Press, 1988 (= Dawra Syr.)

Haddad, P. “Manuscripts of Batnaya Church.” In Haddad, Fahāris al-makhtūtāt, 161-186.

Haddad, P. “Manuscripts of Telleskef Church.” In Haddad, Fahāris al-makhtūtāt, 187-198.

Ashbrook Harvey, S. “Women’s Service in Ancient Syriac Christianity”. In Kanon XVI. Yearbook of the Society for the Law of the Eastern Churches: Mother, Nun, Deaconess, Images of Women according to Eastern Canon Law. Egling: Edition Roman Kovar, 2000, 226-241.

Maclean, A.J.East Syrian Daily Office. London: Rivington, Percival & Co., 1894.

Magdasi, M. “Manuscripts of the Chaldean Archbishopric in Mosul.” In Haddad, Fahāris al-makhtūtāt, 7-20.

Mateos, J. Lelya-Sapra. Essai d’interprétation des matines chaldéennes. OCA 156. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1959.

Mengozzi, A. Israel of Alqosh and Joseph of Telkepe. A Story in a Truthful Language, Religious Poems in Vernacular Syriac (North Iraq, 17th century) 2 vols. CSCO 589, 590, Scryptores Syri 230, 231. Louvain: Peeters 2002.

Mingana, A. Catalogue of the Mingana Collection of Manuscripts, now in the Posession of the Trustees of the Woodbrooke Settlement, Selly Oaks, Birmingham. Cambridge: Heffer, 1933-1939.

Murre-van den Berg, H.L. “A Syrian Awakening. Alqosh and Urmia as Centres of Neo-Syriac Writing.” In Symposium Syriacum VII, Uppsala University, Department of Asian and African Languages, 11-14 August 1996. OCP 256, ed. R. Lavenant, S.J. Rome, 1998: 499-515.

Murre-van den Berg, H.L. “The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries.” In Hugoye, Journal of Syriac Studies 2,2 (1999), www.syrcom.cua.edu/Hugoye/index.html

Nau, F. “Notice des manuscripts syriaques, éthiopiens et mandéens, entrés à la Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris depuis l’édition des catalogues.” In Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 6/16 (1911), 271-310.

Şevket Pamuk, “Evolution of the Ottoman Monetary System”, in Halil İnalcik and Donald Quataert, An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, vol. ii, 947-980.

Perkins, J. Missionary Life in Persia: being glimpses of a quarter of a century of labors among the Nestorian Christians. Andover: Allen, Morill & Wardwell, 1863.

Rosen, V., and Forshall, J. Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum orientalium qui in Museo Britannico asservantur; Pars I, Codices syriacos et carshunicos amplectens. London: 1838.

Sana, H. (e.a.). “Manuscripts of Al-Qosh Church.” In Haddad, Fahāris al-makhtūtāt, 209-73.

Sachau, Eduard. Verzeichniss der Syrischen Handschriften der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin. Die Handschriften-Verzeichnisse der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin 23, Berlin: A. Asher & Co., 1899, 2 vols.

Scher, A. “Notices sur les mss. syriaques et arabes conservés à l’archevêché chaldéen de Diarbekr.” In Journal Asiatique 10 (1907), 332-62.

Scher, A. “Notices des manuscrits syriaques et arabes conservés dans la bibliothèque de l’évêché chaldéen de Mardin.” In Revue des bibliothèques 18 (1908), 64-95.

Scher, A. “Notices sur les manuscrits syriaques conservés dans la bibliothèque du couvent des Chaldéens de N.D. des Semences.” In Journal Asiatique 7 (1906), 479-512 and 8 (1906), 55-82.

Scher, A. “Notice sur les manuscrits syriaques conservés dans la bibliothèque du patriarcat chaldéen de Mossoul.” In Revue des bibliothèques 17 (1907), 237-60.

Scher, A. Catalogue des manuscrits syriques et arabes conservés dans la bibliothèque épiscopale de Seert (Kurdistan). Mosul: Imprimerie des pères dominicains, 1905.

Surma d’Bait Mar Shimun, Assyrian Church Customs and the Murder of Mar Shimun, Vehicle editions, ca. 1920.

Vosté, J.M. Catalogue de la bibliothèque syro-chaldéene du couvent de N.D. des Semences, près d’Alqosh (Iraq). Paris, Librarie Orientaliste P. Geuthner: 1929 (reprint from Angelicum 1928).

Vosté, J.M. “Catalogue des manuscrits syro-chaldeens conservés dans la bibliothèque épiscopale de cAqra (Iraq).” In OCP 5 (1939), 368-406.

Voste, J.M. “Catalogue des manuscrits syro-chaldéens dans la bibliothèque de l’archevêché chaldéen de Kerkouk (Iraq).” In OCP 5 (1939), 72-102.

Vosté, J.M. “Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.D. des Semences.” In Le Muséon 43 (1930), 263-316.

Wilmshurst, David. The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. CSCO 582, Subsidia 104. Louvain: Peeters, 2000.

Wright, William, A Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts preserved in the Library of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: University Press, 1901, 2 vols.

Footnotes

1 See appendix, no. 30.

2 The appendix contains a list of women’s names taken from the primarily Syriac colophons in MSS. written by Church of the East copyists between 1500 and 1830. The list is gleaned from David Wilmshurst’s list of colophons of Syriac manuscripts, in The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913, CSCO vol. 582, Subsidia 104 (Louvain: Peeters, 2000). When the catalogues were available to me and provided extra information on the women and the MSS., such information has been added. Note that Wilmshurst did not include the Arabic MSS. produced by Church of the East writers in this period. Note also that my timeframe is considerably shorter than that of Wilmshurst, who covers the period from 1318 to 1913. I have limited myself to the ‘Ottoman period’, but with the exclusion of most of the nineteenth century, because of the largely different circumstances (considerable western influence) and abundance of sources from about 1830 onwards.

3 My numbers are based on the colophon descriptions in Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation. Although he seems to have taken into account all manuscripts that are described in the catalogues, the often rather concise way in which the MS. colophons are edited suggests that a study of the MSS. itself would yield additional information.

4 To my knowledge, women in the colophons in similar manuscript traditions have not been studied in extenso, cf., e.g., the absence of any particular reference to women in the study by Sanjian K. Avedis: Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480. A Source for Middle Eastern History, Harvard Armenian Texts and Studies 2 (Cambridge (Mass): Harvard University Press, 1969), p. 9-14.

5 Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation, 244, 249, 251.

6 See H.L. Murre-van den Berg, “A Syrian Awakening. Alqosh and Urmia as Centres of Neo-Syriac Writing”, in Symposium Syriacum VII, Uppsala University, Department of Asian and African Languages, 11-14 August 1996, OCP 256, ed. R. Lavenant, S.J. (Rome: 1998), 499-515, and Alessandro Mengozzi, Israel of Alqosh and Joseph of Telkepe. A Story in a Truthful Language, Religious Poems in Vernacular Syriac (North Iraq, 17th century), 2 vols. CSCO 589, 590, Scryptores Syri 230, 231 (Louvain: Peeters 2002).

7 See H.L. Murre-van den Berg, “The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries” [Hugoye, Journal of Syriac Studies 2:2 (1999), ].

8 The difference between commissioning (ysep), and sponsoring (‘giving money’ – cf. no. 38) is unclear. In many cases only commissioning is mentioned and we are left to assume that commissioning in those cases included providing the money. In other cases commissioners and sponsors are mentioned separately, which might suggest a different role for each.

9 I use the term donor/donating in the case of already existing MSS. or other valuables, such as land and/or houses.

10 In at least two cases I have not been able to ascertain whether the name of the parent refers to a man or a woman: Maryam, daughter of Mima of Erbil (1559, no. 4), and Seltana, daughter of Belgana of Bet Megali (ca. 1593, no. 8). There is also one instance of a male scribe who gives only the name of his mother (the deacon Giwargis, son of the believing woman Gozal, 1704, no. 27).

11 Curiously enough, the copyist of the second MS. seems to be the same cAbdishoc of Zangish who accepted a MS. as his daughter’s dowry. In both cases, the names of three or four witnesses (all men, different in each case) are added.

12 The presence of these different types of religious women raises some issues that cannot be adequately treated in this article. One is the apparent survival of the earlier offices of both ‘deaconess’ and ‘daughter of the covenant’, although we learn next to nothing about the content of these offices (on these in the early days, see S. Harvey Ashbrook, “Women’s Service in Ancient Syriac Christianity”, in Kanon XVI. Yearbook of the Society for the Law of the Eastern Churches: Mother, Nun, Deaconess, Images of Women according to Eastern Canon Law (Egling: Edition Roman Kovar, 2000, p. 226-241). The other interesting issue is the possibility that the nun Shmuni was involved in the early stages of the Chaldean monastic movement, initiated in 1808 by Gabriel Danbo in Alqosh; cf. S. Bello, La congregation de S. Hormisdas et l’église chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle, OCA 122 (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1939), although Bello does not mention female involvement.

13 Although I do not have direct evidence for the age at which girls generally were married, somewhere between twelve and sixteen seems likely.

14 Surma d’Bait Mar Shimun, Assyrian Church Customs and the Murder of Mar Shimun, Vehicle editions, ca. 1920, p. 32.

15 For detailed maps, see Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation.

16 This is probably due to the fact that inscriptions from other regions have not been edited, whereas the Salmas inscriptions were edited by Rubens Duval.

17 Sanam of Daralik in Sulduz (1770, no. 54) and Banusheh from Gulpashan in Baranduz (1813, no. 62).

18 See no. 6 (pre-1581), no. 8 (ca. 1593) and no. 33 (1710).

19 Syriac/traditional names: Tamar, Shmuni (8x), Maryam (8x), Helen (5x), Qudsiya Hormez, Meskinta, Marta, Sara, and Elisabeth. I wonder whether Elfiya (3x) and Nasimo (<Onesima?) should be added here as well. Popular non-traditional names are: Hatun (2x), Naze (2x), Maya (2x), Gozal (2x) and Dalle (2x).

20 As was observed also by J.M. Fiey, Mossoul chrétienne. Essai sur l'histoire, l’archéologie et l’état actuel des monument chrétiens de la ville de Mossoul. Recherches publiées sous la direction de l’Institut de lettres Orientales de Beyrouth 12 (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique Beirouth, 1959), 114.

21 In this respect, compare also no. 58, another MS. from Telkepe, which was commissioned thirty-four years later (1778) by a group of “believing women” whose names are not given. This MS. was copied by the same scribe and donated to the same monastery of Giwargis Bet cAwire.

22 For a better insight in the prices of manuscripts, a separate study of all prices in the colophons would be needed. Prices for MSS. in connection with women donors are: 10 shahiye (ca 1593, no. 8), 60 msrt’ (not identified), 12½ qarushe (1660, no. 14), 5 “piasters” (ca. 1700, no. 24). Around 1700 one manuscript constituted a dowry (no. 23). A qurush (or akçe) was the Ottoman standard silver currency, while the shahi (or dirham) was a similar coin minted in the eastern provinces with a view to the Persian market. For further details, see Şevket Pamuk, “Evolution of the Ottoman Monetary System”, in Halil İnalcik and Donald Quataert, An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), vol. ii, 947-980.

23 Of the women’s fathers, three are chiefs (two of them also being a priest or a deacon), seventeen are priests, one a merchant. Three women are called ‘lady’ (khatun) which probably indicates an important family, and one father is called ‘glorious’, which gives a total of twenty-four women that probably come from important families, compared to sixteen cases where the colophon does not give additional information on the father’s status. In addition, one father is a smith and two are deacons.

24 Two priests, two deacons, and eight without title.

25 Two priests, one deacon-copyist, one patriarch and three without title.

26 Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation, 251.

27 However, she ordered it together with a certain Hoshaba, which may exclude the possibility that she actually wanted it for her own use.

28 Four more MSS. could have been commissioned for private use: no. 3 (ca. 1550 “collections diverses”), copied “for Putta, the sister of the copyist”; no 61 (1813), commissioned “for the believing woman Daris Sargis; no. 63 (1824, ‘Book of the seven hours’), commissioned by the nun Shmuni; no. 65 (1826, funeral offices for priests), “commissioned by Kafo of Bidwil for his daughter Gozal”.

29 To what extent women (including religious women) in this period were able to read is difficult to ascertain. The missionaries in Urmia believed that in the early nineteenth century only the sister of the patriarch, Helena, could read, cf. Justin Perkins, Missionary Life in Persia: being glimpses of a quarter of a century of labors among the Nestorian Christians (Andover: Allen, Morill & Wardwell, 1863), 10. However, it is possible that it was not always widely known when women were able to read, whereas it is also possible that in the Alqosh region literacy among women was higher than in the Urmi region. In general, considering the fact that priests and deacons were able to read, one should not be surprised to encounter some degree of literacy among their daughters as well as their sons.

30 Thirty-nine MSS. were copied for, three others were donated to churches and monasteries. In addition, seven donations were made to churches and monasteries, varying from paying for repairs (no. 38), restoration of a MS. (no. 59), and donating money and goods directly (nos. 9 and 10). Only eight colophons do not indicate for which church or monastery the MS. was intended, although three of these did end up in church collections (no. 33 in Jerusalem, no. 51 in the Chaldean monastery in Baghdad, no. 63 in Dohuk), whereas one is in London (no. 61). The four others may be interpreted as commissioned for private use, although it is not impossible that the persons for whom these MSS. were copied were supposed to donate them to a particular church or monastery (for these, see note 28).

31 Of these the Gospel lectionary was the most popular: it occurs seven times (nos 2, 5, 15, 21, 27, 29, 43).

32 Of these, the taksā d-kahnē occurs five times in our list (nos. 30, 44, 47, 48, 60), the hudrā six times (9, 10, 12, 18, 40, 57), the gazzā five times (14, 20, 31, 55, 38), and the kashkol once (no. 33). Note that the hudrā is by far the largest of all liturgical books, but despite its size (and presumably its considerable price), it is almost as popular as the Gospel lectionary. On the difference between the various office books, cf. J. Mateos, Lelya-Sapra. Essai d’interprétation des matines chaldéennes, OCA 156 (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1959), 3-14, on the liturgy see further G. P. Badger, The Nestorians and their Rituals (London: Joseph Masters, 1852, vol. ii), and A.J. Maclean, East Syrian Daily Offices (London: Rivington, Percival & Co., 1894).

33 Various hymn books (church hymns of a later date than those included in the hudrā or gazzā) occur five times in the list (nos. 7, 37, 44, 49, 52).

34 Funeral madrashe (nos. 41, 65), bacuta [d-Ninwāyē] (nos. 16, 51).

35 A commentary on the Psalms for a monastery (1710, no. 32), a ‘Book of Saints’ Lives’ for the church of Mar Miles in Tel-Hash (1697, no. 22), the ktābā d-rīshānē (‘Book of Governors’) of Thomas of Maraga for the church of Mar Isaac in Tella (1701, no. 25).

36 Most editors of the colophons did not bother to give the extensive and detailed information on the donors; much more will probably be found when the original MSS. are studied.

37 V. Rosen and J. Forshall, Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum orientalium qui in Museo Britannico asservantur; Pars I, Codices syriacos et carshunicos amplectens (London: 1838), 56.

38 A third example might be found in no. 62 (1813).

39 Nos. 13 and 35. In the last case, this phrase follows immediately on the reference to her financial contribution.

40 Such a contribution to the community is lovingly described in the funeral inscription of Nazekhatun (1631, no. 13).

41 Note that only very few traces of Neo-Aramaic occur in the colophons. Although the modern language was used for poetry in the same period, it was hardly used in correspondence or other types of ‘free writing’ such as the colophons.