Priests, Laity and the Sacrament of the Eucharist in sixth century Syria†

The Eucharist formed the visible boundary between Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians in the fifth and sixth centuries. Non-Chalcedonian texts emphasize the difference of the Eucharists, but this does not necessarily imply that it was a widely accepted view. This paper analyzes the understanding of the Eucharist among parish priests and the laity.

[1] At the end of the fifth century, the non-Chalcedonian John Rufus, allegedly the bishop of Maiuma in Palestine, wrote about his deceased spiritual father Peter the Iberian who had been bishop of Maiuma in 452/3 CE:1 "And he celebrated the entire [liturgy of the] Eucharist: when he came to the breaking of the almighty bread, with continuous [lit. entirely] weeping and disturbance of his heart and many tears, as it was custom to him, so much blood burst forth when he broke [the bread] that the entire holy altar was sprinkled [with blood]." When he turned around he saw Christ next to him who told him: "‘Bishop, break [it]! Don’t fear. For my glory I did this, and not for yours; that everyone learns of what manner the truth is, and who are those that hold the glory of the right faith.’"2

[2] Peter was a famous non-Chalcedonian bishop and saint who spent most of his life wandering from place to place in Egypt and Palestine. His follower and hagiographer John Rufus wrote Peter’s life shortly after Peter’s death in 491 CE.3 In a recent article, Vincent Déroche points out that this story does not illustrate any theology of the Eucharist, but the Eucharistic miracle is used here in an instrumental fashion.4 The hagiographic texts should demonstrate to the non-Chalcedonian reader or listener that Christ is on the side of the non-Chalcedonians and that communion forms the visible boundary between Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians. Taking the Eucharist from the hands of an "orthodox"—i.e., a non-Chalcedonian—priest is part of practicing the right faith—and this is described as necessary for salvation.5 John bar Qursus was the bishop of Tella, a small town in the province of Osrhoene east of the Euphrates, and one of the prominent Syrian non-Chalcedonian leaders after 519 CE. He demonized the Chalcedonians when he wrote that their Eucharist should be avoided like "the poison of death."6

[3] However, these texts reflect only how the clergy, especially the bishops, wanted to present the sacrament of the Eucharist to the laity, not what the supposed recipients thought of it. It may be therefore worthwhile to circumvent the idealized image of the Eucharist that hagiographic texts present by analyzing the interactions of the average non-Chalcedonian layperson with his (parish) priest. The local priest represented the church, and what he taught the laity would certainly shape their understanding of the Eucharist.7

[4] Although also bishops wrote the sources used here, Severus’ letters, in which the non-Chalcedonian patriarch of Antioch (512-518 CE) dealt mainly with ecclesiastical problems, and John of Ephesus’ Lives of the Eastern Saints, written in 566/8 CE, give some hints concerning the average priest and the laity.8 Furthermore, a mainly unexplored source for the 6th century constitute the canons and decisions given in form of questions and answers: these are legal texts, rules for the life of the church preserved in ecclesiastical synodica.9 Several of these texts were written between 521 and 538 CE—a time when the emperor Justin I exiled non-Chalcedonian bishops because they refused to sign the papal libellus which became the cornerstone of Orthodoxy for the Chalcedonians after 518 CE.10 These canons originated as exchange between the exiled non-Chalcedonian bishops and their flock, which approached their shepherds with questions concerning the ecclesiastical life of their communities.11 Other canons suggest that bishops perceived problems among the priests or in the church communities and tried to correct them by sending admonishing letters or reminding their communities of the appropriate church canons.12 This paper suggests that between 510 and 540 CE the laity and to a certain extent also the priests had only a vague understanding of the Eucharist if any.

[5] Some villages did not have a priest at all who could instruct the laity about the importance of the Eucharist. In that case, the canons ruled that the deacon should take the offerings from the villagers, and go to the nearest village in which a priest lived. He should ask the priest to consecrate the bread, and on his return the deacon should hand it out to the villagers.13 However, according to John of Ephesus’ story of Simeon the Mountaineer, not every village had its own deacon, and was also not enthusiastic to change this. When in 515 CE Simeon reached a quite prosperous village near the Euphrates, bordering to the territory of Claudias, and inquired about their church and how they would receive communion, some of the villagers laughed at him and said: "‘How, blessed sir, does the oblation that a man receives profit him? For what [purpose] is the oblation?’"14 Nevertheless, these shepherds felt quite offended when Simeon asked them if they were Jews. They wholeheartedly considered themselves to be Christians although they had been cut off from the sacraments for years. The shepherds even related to the saint that people lived in the mountains who did not know what a church was, and most of their fellows had only seen one at the time they were baptized as children or when their own children were baptized. The neighboring village still had a church, but it was no longer in use, and one of the villagers told Simeon that they would receive the Eucharist only if they had business in a village which had a priest: "‘If not, no one here has this concern for the oblation.’" John of Ephesus, of course, intends to point out the villagers’ outrageous unchristian behavior in order to make the achievement of his saint—who installed himself as priest in the second village—even greater. Nevertheless, it is obvious that not every village had a priest and it is necessary to ask why.

[6] An answer may be found if it is possible to find out who became a priest and how. It was important that prospective members of the clergy be taught the Scriptures, and John of Ephesus, recording the achievements of John of Tella, was anxious to point out that the bishop of Tella was very careful in selecting his candidates for the priesthood. John of Tella was "performing the ordinations after careful investigation and many testimonies given, subjecting every man to a careful examination and test in reading the Scriptures and repeating the psalms, and ability to write their names and signatures."15 This statement is hard to reconcile with the biographer’s claim that John ordained sometimes fifty or even a hundred priests a day. Even basic knowledge about the Scripture and the canons of the church may have not been known by all priests. However, as it is reasonable to assume that John of Tella’s Canons—which were written for priests "particularly [for] those who are in the villages"—supplemented his practical work of performing ordinations, it seems that John of Tella had perceived this problem and tried to enhance his candidates’ education.16

[7] Nevertheless, when village priests are mentioned in the texts they often appear as "of great ignorance" and making "many transgressions" at best—or fornicating, having two wives, and defecting from the true faith at worst.17 There may be several explanations for the low educational level or improper conduct of the priests.18 The villagers reminded Simeon the Mountaineer that their children "have not time to leave the goats and learn anything."19 Aristocratic parents probably sent their children often to secular places of learning instead of preparing for the priesthood.20 A specific non-Chalcedonian problem at this time might have been that the non-Chalcedonian monasteries—an obvious place of learning especially of the orders of the church21—were shut down for years in the regions around Amida and Edessa.22

[8] However, in many villages able candidates might have been available, but it seems that nevertheless inept candidates were often chosen for this office instead. John of Tella complained that suitable, but poor candidates were not ordained because a richer candidate had paid a bribe in order to be ordained to the office.23 It seems unlikely that money changed hands as such an obvious form of bribery could be easily condemned by long established church canons.24 However, a more subtle form of bribery may have been quite common: well-to-do candidates would "give certain precious gifts to the church as ‘offerings of the priesthood’; and again to the villagers they give another present in exchange for the banquet of joy of the [recent] ordination [lit. priesthood]."25 The gifts to the church might have been, in exceptional cases, expensive liturgical vessels like the chalice which is part of the Beth Misona Treasure and which was donated by a priest.26 Although it is unlikely that the average village priest could afford such offerings, the gifts given on his installation to the church might have been an opportunity for the new priest to present himself as a benefactor of the church and his village. It might have been a gift to embellish the church or add to its equipment, or an endowment which would then allow the newly ordained to fulfill his duties as village priest—like hosting strangers or protecting the poor, orphans and widows.27

[9] Therefore a well-to-do man who became priest would make the local church more powerful, while at the same time he would increase his own social status. As priest he became a respected figure in the village and might have been treated as a guest of honor at banquets or feasts in the village.28 In a society which believed that people could be possessed by demons and would not allow them to take part in the communion, the priest was influential as he could suspend people from communion temporarily, or even excommunicate or anathematize them. The canons show that priests abused this power in order to anathematize people out of vengeance or for other personal reasons.29

[10] The villagers must have been aware of these problems. Therefore the question remains: why did the villagers nevertheless accept rather unsuitable candidates for the priesthood? An answer may lie in the advantages a well-to-do priest brought to the villagers. They would be rewarded twice: immediately after the installment as the new priest would enable the villagers to arrange a banquet in order to celebrate the recent ordination. In fact, they could profit also in the long run as the well-to-do priest may have endowed the church with his own money and therefore lighten the burden of the villagers who usually had to contribute to the church’s expenses. As John of Tella reminds the priests, the hospitality for strangers, but also the care of the poor, orphans and widows was a joint-partnership of church, priest and villagers.30 The more the priest could come up with and had endowed the church, the less the villagers had to contribute.31

[11] On the other hand, a poor and dedicated priest was likely to pester the villagers more often to spend money on the church to finance its duties. He would always be on the payroll of the villagers as priests were entitled to "take the tenth and the first-fruits, and receive the offering from the people, and offer [them] for them [i.e., the people] to God."32 In a worst case scenario, this poor priest would be a zealous man like Simeon the Mountaineer. Deceiving the villagers, Simeon took away one third of their children and dedicated them to the church.33 The villagers reacted with pure hatred for having lost a much needed work force, and only a miracle could save Simeon’s work.34

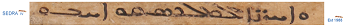

[12] Outside hagiography, the zealous priest does not show up, but in the canons only the type of well-to-do and inept priest can be found.35 Although he was not a burden for the villagers, such a priest could not bring any spiritual profit to them either. Some of the priests were not aware of which things were supposed to be in the sanctuary and on the altar. John of Tella’s rule that martyr bones—although profitable for the sick—should not lie around on the altar shows that negligent priests left them there.36 Worse, however, some priests were apparently even unable to consecrate the Eucharist:37

[13] It came to our attention that [certain] people [i.e., priests] from the villages, not having learned completely38 the offering of the Eucharist, transgress boldly39 and ascend [to the altar] at the awe-inspiring moment: they offer the Eucharist, and when they pray they are confused and a cause of laughter and improper talk40 at [this] moment for those who are gathered for prayer.41

[14] Mistrusting the character of these local non-Chalcedonian priests might have led some more privileged non-Chalcedonian laypersons write to Severus, the patriarch of Antioch, to ask him to send them the Eucharist.42 Severus denied most requests since Gregory Nazianzus had already condemned the custom of some laypersons who preferred to receive the sacraments from clergy whom they believed to be morally sound, or maybe even holy.43 Severus assured his addressees that the priest "fulfils a mere subsidiary function only, [and] makes no addition whatever to the rites that are performed, although he be an angelic and heavenly man in his character, nor does he detract anything from the divine grace, if he has lived a degraded and low life."44

[15] The dark image of the village priest can be balanced by two documents that suggest that at least some clergy cared for proper instructions. Sergius, a priest, asked John of Tella forty-eight questions concerning liturgical issues which the bishop answered meticulously.45 What was he to do with a vessel which could no longer be used for the liturgy? What was he to do with a sponge that could no longer be used for cleaning? What should Sergius do with the water that was used for cleaning the vessels?46 The majority of the questions concern the Eucharist: What was to be done when a particle of the Eucharist or some of the holy blood fell to the ground?47 Could a layperson bring the Eucharist to the sick, and could someone who had eaten or someone whose "blood goes from his nose into the throat" take the Eucharist?48

[16] The second document provides an answer by John of Tella to a deacon’s inquiry about how he had to prepare the Eucharist, and what his tasks were in the sanctuary.49 John explained only the physical steps, but remained silent about what the deacon actually had to say in the liturgy. It may well be that the village in which the deacon served had a book of the liturgy available where the deacon could look that up.50

[17] These texts demonstrate the need for basic knowledge concerning the sacramental life of the church as well as some clerics’ desire to learn what they needed to know. The essential problem remains that priests and deacons could not learn their profession in the cathedral of their bishops because their bishops were in exile. Bishops like John of Tella had to send instructions by letter from exile. These letters also show the concern of the exiled non-Chalcedonian bishops: would the priests stand by their bishops or convert under pressure from the Chalcedonians? Several canons deal in part with clergy who had been at some point in the service of the Chalcedonians; they distinguish between clergy who were ordained by non-Chalcedonians and "joined the heretics […] by necessity or by transgression,"51 and clergy who had been ordained by Chalcedonians and later joined the non-Chalcedonians. The former seem to have been quite common, but the priests had ample reason to defect. They were on the front lines when the papal libellus was enforced in the east 519-522 CE, but not prepared to face this challenge.

[18] When Severus escaped Antioch and went into exile in Egypt in September 518 CE, he left at least part of his clergy behind, which probably then had to deal with Severus’ successor, the Chalcedonian Paul "the Jew."52 The clergy in Tella seemed to have been in an even more difficult situation. At a time when the emperor Justin already enforced Chalcedon west of the Euphrates, John became bishop of Tella in 519 CE. Part of the nobles and clergy thought "‘[i]f the imperial edict should also come here requiring that we accept the Council of Chalcedon, then we would easily persuade him [John of Tella] to accept it, since this is nothing. There are none who can really stand against the imperial order.’"53 However, John surprised the nobles and clergy of Tella with his willingness to oppose the imperial will.54 He erased from the diptychs all Chalcedonian names—probably bishops of Tella.55 When two years later Chalcedon was enforced also in Osrhoene, John had to leave the city, and there can be no doubt that the new Chalcedonian bishop erased John from the diptychs.

[19] If Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian bishops alternated several times, as had certainly been the case in Tella, then this instability must have left theologically less trained lower clergy numbed and confused about which Eucharist was orthodox. They may have accepted the different christological preferences of their overlords without opposition.56 The non-Chalcedonians were threatened by the fact that Chalcedon was now backed up by an imperial edict which, as quoted above, made an impact on the nobles and clergy of Tella. It is highly likely that the lower clergy in most towns in the East—left behind by their non-Chalcedonian bishop—first accepted the libellus as the canons also forced them to obey their bishops.57 That would mean that "defections," or rather the shifting of loyalty, may have been more common among the average priests than it was among bishops and monks. In this situation the average priest may not have been able to live up to his supposed duty to give spiritual guidance to the laity and advise them on the sacrament of the Eucharist.

[20] In conclusion, the high cosmological boundary between Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians drawn in hagiography was more permeable in everyday life in the cities and villages in the East. Some villagers were completely cut off from the sacrament, and did not have the desire to get a priest who would take away the tenth of their harvest. In their understanding, baptism was crucial and would make them Christians regardless of whether they took the Eucharist or not. Other villagers probably did not know much about the Eucharist because it is likely that their priests did not know much about this sacrament either.

[21] The addressees in Severus’ letters were certainly not the average laity, but aristocrats who obviously cared for the Eucharist. They wanted to receive the sacrament from someone who was like the saints they knew from reading the non-Chalcedonian hagiographic accounts—someone like Peter the Iberian. They believed that this would ensure the validity of the sacrament, certified by the celebrant who, like Severus of Antioch, lived up to the standards set in hagiographic accounts. Other non-Chalcedonians may have also seen a division between Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians but, like the nobles and clergy in Tella, considered the imperial edict paramount. It was therefore the bishops who tried to draw a clear line, and enforce the understanding of the "orthodox" Eucharist as necessary for salvation, but the demarcation often had less impact on their followers than the bishops may have wished.

_______ Notes

† I would like to thank Peter Brown, Manolis

Papoutsakis, Craig Caldwell, Brooke Blower and an anonymous

reviewer for helpful comments.

Banaji, J., Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity. Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance, Oxford: Oxford University Press, c2001.

The Biography of John of Tella by Elias, trans. J. R. Ghanem. Diss. Madison/WI, 1970.

The Chronicle known as that of Zachariah of Mitylene, trans. by F.J. Hamilton and E.W. Brooks. London: Methuen & Co., 1899.

The Chronicle of Zuqnin Pars III and IV A.D. 488-775, trans. A. Harrak. Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies: Toronto, c1999.

Corpus Iuris Civilis, Vol.3: Novellae, ed. R. Schoell and G. Kroll, Dublin: Weidmann, 1972.

Déroche, V. "Représentations de l’eucharistie dans la haute époque Byzantine." in Mélanges Gilbert Dagron, Travaux et Mémoires 14 (2002): 167-180.

The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius, ed. J. Bidez and L. Parmentier. London: Methuen, 1898.

The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus, trans. M. Whitby. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, c2000

Elias, Life of John of Tella, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks in Vitae virorum apud Monophysitas celeberrimorum, CSCO 7-8. Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae, 1907.

Fortescue, A. The Reunion Formula of Hormisdas. Garrison, N.Y.: National Office, Chair of Unity Octave, 1955.

Gregory of Nazianzus Discours 38-41, ed. and trans. C. Moreschini and Paul Gallay, SC 358. Paris: CERF, 1990.

Haacke, W. Die Glaubensformel des Papstes Hormisdas im Acacianischen Schisma, Analecta Gregoriana 20. Rome: Apud Aedes Universitatis Gregorianae, 1939.

Harvey, S. Ashbrook Asceticism and Society in Crisis. John of Ephesus and The Lives of the Eastern Saints. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990.

Honigmann, E. "The original Lists of the members of the Council of Nicaea, the Robber-Synod and the Council of Chalcedon." Byzantion 16 (1942/3): 20-80.

—, Évêques et Évêchés Monophysites d’Asie antérieure au Vie siècle, CSCO 127, Subsidia 2. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1951.

Horn, C. Beyond Theology: the Career of Peter the Iberian in the Christological Controversies of Fifth-Century Palestine. Diss. Washington D.C., 2001.

Incerti Auctoris Chronicon Pseudo-Dionysianum Vulgo Dictum, ed. I.-B. Chabot, CSCO 104. Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae, 1933.

John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks, in PO 17-19. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1923-25.

John Moschus. Pratum Spirituale 26, ed. Migne in PG 87:3: 2852-3112.

John Moschus. The Spiritual Meadow, trans. J. Wortley, CS 139. Kalamazoo: Cistercian, c1992.

John Rufus. Plérophories, ed. and trans. F. Nau, in PO 8. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1912: 1-208.

Kuberczyk, C. Canones Iohannis bar Cursus, Tellae Mauzlatae Episcopi, e Codicibus Syriacis Parisino et Quattuor Londiniensibus editi. Leipzig: Guil. Drugulini, 1901.

Lamy Th. Dissertatio de Syrorum Fide et Disciplina in Re Eucharistica. Louvain: Vanlinthout, 1859.

Mango, M. Mundell. Silver from early Byzantium. The Kaper Koraon and Related Treasures. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1986.

Moore, R.I. The first European Revolution, c. 970-1215. Blackwell: Oxford, c2000.

Nau, F. Les Canons et les Résolutions Canoniques. Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1906.

Petrus der Iberer. Ein Charakterbild zur Kirchen-und Sittengeschichte des fünften Jahrhunderts, ed. R. Raabe. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1895.

Noethlichs, K.L., "Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Fehlverhalten und Amtspflichtverletzungen des christlichen Klerus anhand der Konzilskanones des 4. bis 8. Jahrhunderts." ZSRG.K 76 (1990): 1-61.

Philoxenus. Lettre aux Moines de Senoun, ed. and trans. A. de Halleux, CSCO 231, 232. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1963.

Poggi, V. and Mar Grigorios, "Il commento al Trisagio di Giovanni Bar Qūrsūs." OCP 52 (1986): 202-210.

Rahmani, I. Studia Syriaca III: Vetusta Documenta Liturgica. Typis Patriarchalibus: Sharfeh, 1908.

Schwartz, E. Johannes Rufus, ein monophysitischer Schriftsteller, SHAW.PH 3.16. Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1912.

—, Publizistische Sammlungen zum Acacianischen Schisma, ABAW.PH N.F. 10. München: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1934.

Selb, W. Orientalisches Kirchenrecht, Vol.1: Die Geschichte des Kirchenrechts der Westsyrer (von den Anfängen bis zur Mongolenzeit), SÖAW.PH 543. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1989.

The Sixth Book of the Select Letters of Severus, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks, 4 Vols. London: Text and Translation Society, 1902-4.

Steppa, J.-E. John Rufus and the World Vision of Anti-Chalcedonian Culture. GDECS 1. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002.

The Synodicon in the West Syrian Tradition, ed. and trans. A. Vööbus, 2 Vols., CSCO 367, 368. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1975.

Vööbus, A. Syrische Kanonessammlungen. Ein Beitrag zur Quellenkunde, 2 Vols., CSCO 307, 317. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1970.

Vries, W. de Sakramententheologie bei den syrischen Monophysiten, OCA 125. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1940.

Wright, W. Catalogue of Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. 2. London: British Museum, 1871.

Wright, W. A Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts preserved at the Library of the University of Cambridge, Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901.

Footnotes

1 About Peter the Iberian see C. Horn’s dissertation Beyond Theology: the Career of Peter the Iberian in the Christological Controversies of Fifth-Century Palestine, Diss. Washington D.C. 2001; for John Rufus and the question of whether he was bishop of Maiuma see J.-E. Steppa, John Rufus and the World Vision of Anti-Chalcedonian Culture, GDECS 1 (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002), 18f.

2 Life of Peter the Iberian, ed. R. Raabe, Petrus der Iberer. Ein Charakterbild zur Kirchen-und Sittengeschichte des fünften Jahrhunderts (Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1895), 56 (English translation mine). The authorship of John Rufus for Peter’s Life, which survived anonymously, was established by E. Schwartz, Johannes Rufus, ein monophysitischer Schriftsteller, SHAW.PH 3.16 (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1912).

3 For the date of Peter’s death see E. Schwartz, Publizistische Sammlungen zum Acacianischen Schisma, ABAW.PH N.F. 10 (München: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1934), 211 note 2.

4 V. Déroche, "Représentations de l’eucharistie dans la haute époque Byzantine," in Mélanges Gilbert Dagron, Travaux et Mémoires 14 (2002), 167-180, here 170f. See also W. de Vries, Sakramententheologie bei den syrischen Monophysiten, OCA 125 (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum 1940), 142-155.

5 For right communion as necessary precondition for salvation: the non-Chalcedonian John Rufus, Plérophories, 87 ed. F. Nau, PO 8 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1912), 140f; the Chalcedonian John Moschus, Pratum Spirituale 26, ed. Migne in PG 87, 2872; trans. into English by J. Wortley, The Spiritual Meadow, CS139 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian, c1992), 17-19. Cf. also S. Ashbrook Harvey, Asceticism and Society in Crisis. John of Ephesus and The Lives of the Eastern Saints (Berkeley: University of California Press c1990), 101.

6 Communis opinio is that John of Tella and John bar Qursus (with various spellings in the manuscripts), bishop of Tella de-Mauzelat, were the same person. He is called John of Tella in his two biographies by Elias and John of Ephesus, and an unpublished letter in which he states his faith (BL Add. 14549, fols. 219b-226b; W. Wright, Catalogue of Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. 2 (London: British Museum 1871), 431). He is called John bar Qursus in his Canons (see note 16), Questions and Answers (see below), Comment on the Trisagion (V. Poggi, Mar Grigorios, "Il commento al Trisagio di Giovanni Bar Qūrsūs," OCP 52 (1986), 202-210) and an unpublished letter to a deacon (Cambr. Add. 2023, fols. 250b-252b; cf. W. Wright, A Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts preserved at the Library of the University of Cambridge, Vol. 2 [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901], 622.). See also E. Honigmann, Évêques et Évêchés Monophysites d’Asie antérieure au Vie siècle, CSCO 127, Subsidia 2 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1951), 51f. "Poison of death:" John of Tella, Questions and Answers 44. The text is difficult to date (sometime between 521 and John’s death in 538 CE), and survived in several different versions. For an overview see A. Vööbus, Syrische Kanonessammlungen. Ein Beitrag zur Quellenkunde, Vol. 2, CSCO 317, (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1970), 263-5. It was first edited with Latin translation by Th. Lamy in Dissertatio de Syrorum Fide et Disciplina in Re Eucharistica (Louvain: Vanlinthout, 1859), 61-97. A slightly different version which is more accessible (with English translation) can be found in The Synodicon in the West Syrian Tradition, ed. and trans. A. Vööbus, 2 Vols., CSCO 367, 368 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1975), Ed. in CSCO 367, 211-221 [Trans. in CSCO 368, 197-205].

7 Although certainly very influential on a local level, village priests are not well represented in the sources. As R.I. Moore, The first European Revolution, c. 970-1215 (Blackwell: Oxford, c2000), 60 rightly states for the village priest in Europe: "At most periods in European history the parish priest is a figure as poorly documented as he is obviously influential."

8 The Sixth Book of the Select Letters of Severus, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks, 4 Vols. (London: Text and Translation Society 1902-4); John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks, in PO 17-19 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1923-25).

9 Fundamental are A. Vööbus, Syrische Kanonessammlungen. Ein Beitrag zur Quellenkunde, 2 Vols., CSCO 307, 317, (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1970) and W. Selb, Orientalisches Kirchenrecht, Vol. 1: Die Geschichte des Kirchenrechts der Westsyrer (von den Anfängen bis zur Mongolenzeit), SÖAW.PH 543 (Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1989), here especially 88-92. Edition and translation of one version of the synodicon see: The Synodicon, ed. and trans. Vööbus (as note 6).

10 Canons of Ordinations were probably written earlier, at the end of fifth/beginning of sixth century; Vööbus, Kanonessammlungen I.1, 146-156. Every bishop in the East had to sign the libellus, but fifty-four non-Chalcedonian bishops preferred exile. For the libellus see: W. Haacke, Die Glaubensformel des Papstes Hormisdas im Acacianischen Schisma, Analecta Gregoriana 20 (Rome: Apud Aedes Universitatis Gregorianae, 1939) and A. Fortescue, The Reunion Formula of Hormisdas (Garrison, N.Y.: National Office, Chair of Unity Octave, 1955).

11 Therefore they may be preserved in different forms: Extracts from a letter by John of Tella (Cambr. Add. 2023, fols. 250b-252b) seem to bear the same content as six canons which are preserved in Sharfeh 4/1 (cf. Vööbus, Kanonessammlungen I, 236-240. I did not have a chance to see the Sharfeh manuscript). The letter may have been the original form of the text although today the canons seem to preserve the text more complete.

12 For example John of Tella’s Canons (see note 16).

13 Canons of Ordinations, [4], ed. and trans. by Ignatius Rahmani, Studia Syriaca III: Vetusta Documenta Liturgica, Typis Patriarchalibus: Sharfeh, 1908, kw [=26] [Trans. 57].

14 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, in PO 17, 233 (for the date see 245).

15 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, in PO 18, 518. Cf. Harvey, Asceticism and Society in Crisis, 100-103.

16 John of Tella Canons, easily accessible with English translation in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 145 [Trans. 142]. First edited from other manuscripts by Carolus Kuberczyk, Canones Iohannis bar Cursus, Tellae Mauzlatae Episcopi, e Codicibus Syriacis Parisino et Quattuor Londiniensibus editi (Leipzig: Guil. Drugulini, 1901); French translation: F. Nau, Les Canons et les Résolutions Canoniques (Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1906). If John of Tella started to ordain priests sometime before 527 CE (Harvey, Asceticism and Society in Crisis, 101), the Canons can be roughly dated to the same time; see also Vööbus, Kanonessammlungen I, 156-164, but he does not suggest a date.

17 Ignorance: From a Letter which one of the venerable Bishops wrote to his Friend, 2, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 180f [Trans. 171f ]; transgressions: John of Tella, Canons post scriptum, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 156 [Trans. 151]; fornicating: Severus, Select Letters I. 41, ed. Brooks, 130 [Trans. 116]; two wives: From a Letter which one of the venerable Bishops wrote to his Friend, 8, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 182 [Trans. 173]; defecting: Ecclesiastical Canons which were given by the Holy Fathers during the time of persecution 1; Chapters which were written from the Orient 32 and 36; From a Letter written by the Holy Fathers to the Presbyters and Rishai Dairata Paula and Paula 1, all in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 159f [Trans. 154]; 173f [Trans. 165f], 174f [Trans. 166f]; 177 [Trans. 168f]. These texts were written c. 532-535CE; see Vööbus, Kanonessammlungen I-II, 269-273, 167-175, 164-167.

18 Complaints about priests are almost as old as the office; for a thorough compilation of transgressions of clergy in the ancient and early medieval world according to Greek and Latin accounts see K.L. Noethlichs, "Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Fehlverhalten und Amtspflichtverletzungen des christlichen Klerus anhand der Konzilskanones des 4. bis 8. Jahrhunderts" (ZSRG.K 76 [1990]), 1-61.

19 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, in PO 17, 241.

20 As John of Tella in his Canons 27, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 156 [Trans. 151], complains that children were sent "to far off countries because of the instruction of this world."

21 See From a Letter which one of the venerable Bishops wrote to his Friend, 2, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 180f [Trans. 172f], in which it is ruled that a priest who did not know the order of the church should preferably learn them in a monastery.

22 For a decade around Edessa, for at least two decades around Amida; see Incerti Auctoris Chronicon Pseudo-Dionysianum Vulgo Dictum, ed. I.-B. Chabot, CSCO 104 (Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae, 1933), 21-24, 27-30 (trans. into English: Amir Harrak, Chronicle of Zuqnin Pars III and IV A.D. 488-775 (Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies: Toronto, c1999), 53f, 57-59); John of Ephesus’ account on the Amidean monasteries, in his Lives of the Eastern Saints in PO 18, 607-623; see also Ps.-Zachariah Rhetor, H.E. 8.5, ed. and trans. E.W. Brooks, Historia ecclesiastica Zachariae rhetori vulgo adscripta, 4 Vols. CSCO 83-84, 87-88 (Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae 1919-24), here CSCO 84 [Trans. CSCO 88], 80f [Trans. 55f] also translated as The Chronicle known as that of Zachariah of Mytilene, trans. by F.J. Hamilton and E.W. Brooks (London: Methuen & Co., 1899), 209-211.

23 John of Tella, Canons 14, see also 5, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 152f [Trans. 148]; 148 [Trans. 144]. Severus also complained about priests (or bishops?) who bought their office from Flavian, Severus’ predecessor as patriarch of Antioch: Select Letters I. 48, ed. Brooks, 145 [Trans. 131].

24 See John of Tella, Canons 5, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 148 [Trans. 144], referring back to Acts 8:20: "May your silver perish with you, because you thought you could obtain God’s gift with money!"

25 John of Tella, Canons 14, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 152f [Trans. 148]. The translation is my own as Vööbus’ translation is a bit problematic, but seems to be pretty much the same as F. Nau’s French translation (see note 16).

26 The inscription does not say why the priest donated the chalice; M. Mundell Mango, Silver from early Byzantium. The Kaper Koraon and Related Treasures (Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1986), 228. Mango locates Beth Misona south of Antioch and Beroea.

27 John of Tella, Canons 12, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 151f [Trans. 147].

28 See John of Tella Canons 15, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 153 [Trans. 149]. The priests were invited as special guests to banquets to bless the hosts of the banquet, and it seems reasonable to assume that they also stayed as special guests. However, to linger there is exactly what John of Tella requests priests not to do.

29 Chapters which were written from the Orient, 26-29, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 171f [Trans. 164f]: priests suspended or anathematized people out of personal reasons. For suspension from communion see also the story of Simeon the Mountaineer in The Lives of the Eastern Saints in PO 17, 241; for anathema: John of Tella, Canons 3, The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 147 [Trans. 144].

30 See note 27 above.

31 From Justinian’s Novellae it is clear that at least in Chalcedonian churches people paid bribes in order to receive ordination because they would then be paid by the church. In the end, the churches had too many priests to feed and became poor; Novella VI.4 and 8 (and also Novella 3, introduction): Corpus Iuris Civilis, Vol.3: Novellae, ed. R. Schoell and G. Kroll, Dublin: Weidmann 1972, 42 and 45f (18-20). John of Tella, however, seems to write his rules for a different audience.

32 John of Tella Canons 14, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 153 [Trans. 148] (Translation mine).

33 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, in PO 17, 241.

34 For the availability of work force see J. Banaji, Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity. Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, c2001), 180ff.

35 A fact that is of course inherent to this genre in the same way as hagiography only remembers the "good" priest or saint.

36 John of Tella, Questions and Answers 12, The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 213 [Trans. 199].

37 John of Tella Canons 13, in Canones Iohannis bar Cursus, ed. Kuberczyk, 29f which seems to be more reliable than the edition in The Synodicon by Vööbus (Translation mine).

38 Vööbus’ edition, 152 reads "well."

39 Vööbus’ edition, 152 reads "with Authority, particularly," which must be a misprint as he also translates "audaciously."

40 Vööbus’ edition, 152 reads only "talk," but he also translates "improper murmurs."

41 Vööbus’ edition and translation misses "for prayer" which may be due to the manuscript. As John of Tella does not complain the lack of proper ordination, but of instruction for the celebration of the Eucharist, it is reasonable to suppose that "people from the villages" means village priests.

42 Severus dealt with people who asked him to send them the Eucharist in several letters: Severus, Select Letters III.1-4, ed. Brooks 261-282 [Trans. 231-249].

43 Severus, Select Letters III.2, ed. Brooks 265-7 [Trans. 235f] quotes from Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 40.26, ed. with French translation C. Moreschini and Paul Gallay, Discours 38-41, SC 358 (Paris: CERF, 1990), 256-259.

44 Severus, Select Letters III.3, ed. Brooks 269f [Trans. 238f].

45 John of Tella, Questions and Answers in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus 211-221 [Trans. 197-205]. Cf. also Vööbus, Kanonessammlungen II, 263-269.

46 John of Tella, Questions and Answers 1-3, 14; in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 211, 213 [Trans. 197, 199].

47 John of Tella, Questions and Answers 4, 6; in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 211f [Trans. 197f]

48 John of Tella, Questions and Answers 8, 16, 20; in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 212-215 [Trans. 198-200].

49 Cambr. Add. 2023, fols. 240b-252b. See note 6 above.

50 A Church should have books: John of Tella, Canons 14, in: The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 152f [Trans. 148].

51 Canons written during the time of persecution 1; in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 159f [Trans. 154f].

52 Severus, Select Letters IV.8, ed. Brooks 302-304 [Trans. 268-270]. For the date of Severus' flight see: The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius. IV.4, ed. J. Bidez and L. Parmentier (London: Methuen 1898), 155 [English translation by M. Whitby, The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 2000), 203]; for the cognomen of Paul see Philoxenus, Lettre aux Moines de Senoun, ed. and trans. A. de Halleux, CSCO 231, 232 (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO 1963), 75 [Trans. 61].

53 Elias, Life of John of Tella, ed. E.W. Brooks in Vitae virorum apud Monophysitas celeberrimorum, CSCO 7-8 (Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae, 1907), 55 [Trans. from Joseph R. Ghanem, The Biography of John of Tella by Elias (Diss. Madison/WI, 1970), 64f]. Although it is only stated that "some people, those attached to material things, who shunned and despised spiritual things" said the quotation given above, it seems reasonable to conclude that these "people" were part of the nobles and clergy as only those had been gathered by John.

54 John of Tella’s strong opposition to Chalcedon is clearly visible in his—unpublished—letter to the monks around Tella which he probably wrote on his installment as bishop of this city: BL Add. 14549, 219b-226b (see note 6 above).

55 Only Sophronius is mentioned by name; for Sophronius see E. Honigmann, "The original lists of the members of the Council of Nicaea, the Robber-Synod and the Council of Chalcedon" (Byzantion 16 [1942/3]), 51 and 70.

56 Nothing is said about non-Chalcedonian names in the diptychs, but as John apparently erased "only" some names from the diptychs, there must have been also non-Chalcedonian bishops before John who did not erase Chalcedonian names.

57 It is not clear, however, if clergymen who remained in the city were always employed under the new bishop. For obedience to higher clergy, intended of course only for non-Chalcedonians towards a non-Chalcedonian bishop, see John of Tella, Canons 25, in The Synodicon, ed. Vööbus, 155 [Trans. 151].