Jacob of Edessa's version of Exodus 1 and 28†

At the end of the seventh century and into the beginning of the eighth, the Syriac Orthodox scholar Jacob of Edessa produced his own Syriac version of the Old Testament. According to the colophons of the extant manuscripts, this was explicitly a combination of the Syriac and Greek textual traditions. This is in fact borne out by a close study of Jacob's versions of Samuel, Genesis and Exodus. However, it is less obvious what criteria Jacob used for the inclusion or exclusion of the different strands available to him, including the Peshitta, the Syrohexapla, and different recensions of the Septuagint. This paper examines two very different passages in the book of Exodus from the unpublished manuscript of Jacob's version of the Pentateuch.1

[1] By the end of the seventh century the Greek tradition of Scripture was well known among the Syriac churches, and in the West, it was particularly influential. The "separated" gospels in the Old Syriac and Peshitta forms had of course first been translated from Greek. The Philoxenian and Harklean versions of the New Testament were revisions of the Syriac to reflect the Greek original text more closely. In contrast, the Peshitta Old Testament had been translated from Hebrew (and Aramaic), but the loss of the knowledge of Hebrew in the Syriac Church coupled with the dominance of the LXX in the Greek-speaking world, meant that revisions of the Old Testament were made towards the Greek, not the Hebrew. Thus there may be traces of a Philoxenian version of the Old Testament,2 but much more importantly there is the Syrohexapla, translated in 615-17 by Paul of Tella at the Ennaton in Egypt, from Origen's revised text of the LXX in the Hexapla.3 The Syrohexapla attained real importance in the Syriac churches, and readings from it were cited even in the Church of the East by the commentators of the eight and ninth centuries, such as Isho'dad of Merv.4

[2] Driving this production of Syriac scriptural versions reflecting the Greek texts was the great influence of Greek Christianity in the spheres of politics, theology and general culture.This influence also resulted in an enormous number of translations of commentaries and exegetical works from Greek into Syriac.5 The obvious problem withbible commentaries translated from Greek was the type of biblical text they cited: adjusting the citations to the Peshitta form, as the first translations did, often meant that they did not match the author's exegesis which was based on the LXX text. Reproducing in Syriac the LXX form of the original Greek commentary meant presenting the reader with a bible quotation to which they were unaccustomed, and thus the interpretation would be less convincing.6 However, the increasing use of Scripture revisions towards the Greek by such versions as the Philoxenian and Syrohexapla no doubt made Syriac readers more familiar with the Greek tradition of Scripture, and to some degree they must have accepted certain Greek readings alongside those of the Peshitta.

[3] Nevertheless, there is also evidence that Greek aroused mixed feelings among Syrians loyal to their native traditions and bible versions. Notably, although the monks of Eusebona had fetched Jacob of Edessa from Kaisum in order to revive the teaching of Greek Scripture, he was attacked by some of the brothers who hated "the Greeks", and this is how he ended up at Tel 'Ada, where he produced his revision of the Old Testament.7 Given this hostility in certain quarters, and the existence of the Philoxenian and Syrohexapla versions, why did Jacob want to produce yet another version of the Old Testament that, according to some colophons was revised according to the Syriac and Greek traditions? For instance, the colophon at the end of 1 Samuel8 says that the First Book of Kingdoms was "corrected from the different traditions, namely from that of the Syrians and those of the Greeks." Since it is in the singular, the tradition of the Syrians can only refer to the Peshitta and not the Syrohexapla, which may even be included among "those of the Greeks," perhaps alongside the Lucianic recension whose influence is clear in Jacob's version of Samuel.9 However, the wording of the colophon at the end of Numbers differs slightly: "It was corrected from the two traditions, from that of the Syrians and from that [note the singular] of the Greeks."10 Perhaps the Syrohexapla and the LXX texts were regarded as co-terminous in this case, or perhaps the writer was being imprecise. The date and place of the version given by each manuscript is the same, 1016 AG, i.e. 705 CE, in the monastery of Tel 'Ada.

[4] Though small portions of the surviving manuscripts of Jacob's biblical version were already being reproduced and studied more than two centuries ago,11 there is much work still to be done. At present the most work has been done on Jacob's version of Samuel, for which there is a detailed study and also an edition of the text.12 A particular desideratum would be a complete edition of Jacob's version of the Pentateuch. This is preserved in a single manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale Paris 26. Until someone is able to take on such a large project, it may be legitimate to take soundings of the individual books.13 Jacob's version of Genesis has already received a limited amount of attention, but the rest of Jacob's Pentateuch has been largely passed over.

[5] The biblical book of Exodus includes quite disparate material, covering narrative, legal prescriptions, and the description of the Tabernacle. I have chosen two different passages for analysis. The first example, taken from the story of the bondage of the Israelites in chapter 1, is illustrative of Jacob's general approach elsewhere (it can hardly be termed a method).

Exod 1.8 -21 (folios 108 col. a-109 col. a)

[6] Italics indicate the use of identical Syriac wording to that in the Syrohexapla; bold font indicates material that has been translated directly from LXX. Plain type indicates close proximity to the Peshitta text.

- But a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.

- He said to his people, "Look, the people of the children of Israel are more numerous and stronger than us."

- "Come, therefore, let us act wisely towards them, lest they increase, and whenever war befalls us they also be joined to our enemies, and when they make war on us they leave our land."14

- They appointed evil ruling officers over them, to enslave and humiliate them with works and treat them badly (=LXX ίνα κακώσώσιν). They built fortified cities for Pharaoh, Pithom, Ra'amsis and On, which is Beth Shemesh (=LXX ήλίου πόλις).15

- As much as they enslaved and humbled them, thus they grew stronger, and to such a degree they were increasing that the Egyptians wearied of the children of Israel.

- The Egyptians were oppressing and enslaving the children of Israel with cruelty.16

- They embittered (= LXX κατωδύνων) their lives with hard labour, with clay and with bricks and with all types of agricultural work, with every slavery with which they enslaved them by force (= LXX μετά βίας).

- The king of Egypt said to the midwives of the Hebrews,

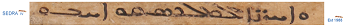

of whom the name of one was Zephora (= LXX

)

and the name of the other was Pu'a,17

)

and the name of the other was Pu'a,17

- He said to them, "Whenever you are assisting the Hebrew women to give birth, you see when they kneel to give birth, and if it is a male, kill him, and if it is a female, preserve her."

- The midwives feared God, and they did not do as the king of the Egyptians commanded them. They saved the males.

- The king summoned the midwives and said to them, "Why have you done this deed and kept alive the male children?"

- The midwives said to Pharaoh, "Not as the Egyptian women are the Hebrew women, because they are lively.18 Before the midwives come in to them, they give birth."

- God treated the midwives well because they did this deed, and the people increased and grew very strong indeed.

- It happened that since the midwives feared God, he made houses for them/they made houses for themselves.

[7] Compared with the situation in other passages in Jacob's versions of Samuel, Genesis and Exodus, much of the additional material Jacob uses seems to be from the Syrohexapla rather than translated directly from LXX as is often the case elsewhere, for instance in Samuel.19 Jacob has effectively expanded the story recounted in the Peshitta, while preserving the Peshitta's wordplay on 'midwives', 'keeping alive', and 'lively'. The latter is a feature only partly present in the Hebrew and not at all in the LXX and Syh versions (it is actually an inner-Aramaic feature found only in the Peshitta and Targums). Aside from that, the reason for Jacob's alterations to his base text of the Peshitta is not clear His approach seems rather casual, in fact, and probably was. In this particular passage his aim seems to be to include as much information as possible from the two traditions, Greek and Syriac, in order to fill out and expand the account. There seems to be no more scientific explanation (in the modern text-critical sense) for changing this particular passage than the one of expanding and including more material in the account.

[8] We might have expected Jacob to explain or defend his version somewhere. However, nowhere in Jacob's work is there an explicit comment from Jacob on what his general criteria are for choosing some readings and not others from the Greek, or Syrohexapla, and whether they replace or only expand on what the Peshitta provides. The colophons mentioned above are too vague in the information they provide about his working methods.

[9] One feature of Jacob's version in both Samuel and the Pentateuch is the provision of marginal notes that give an alternative reading from the other tradition than the one included in his main text. There are also several scholia in both manuscripts that elucidate specific names or problems in the text. Thus in the course of Exodus 28 there is an extensive scholion that sheds some light on Jacob's procedure in one particular passage. It occurs between verses 30 and 31, and occupies most of the top half of a page before the text of the chapter resumes. The subject of the scholion is the high priest's breastpiece and ephod, and it immediately follows the passage in Jacob's version that deals with these very items. The purpose of the scholion is to draw attention to the confusion that has arisen in the text (i.e. that of the Peshitta) concerning the proper terminology for the items called pedtho and perisa. The scholion is positioned between Jacob's version of Exod 28.30 and 28.31, at the top of folio 164, and occupying over one third of the page. Thus it is a prominent and deliberate note that the scribe has written before continuing on with the biblical text. Perhaps the scholion appeared in the autograph of the manuscript, or perhaps it was added from a collection of Jacob's scholia that was circulating separately.

[10] "One should know that many have erred not a little over these terms pedtho and perisa, being unaware of what a pedtho is and what a perisa is. While sometimes they call 'pedtho' the perisa of the judgments that is borne on the priest's breast and contains the twelve gems, at other times they use the term 'pedtho' for the kebinta with which the priest covered (kabben) his shoulders, and in which were the two emeralds on both his shoulders at the front, and to which was also bound the perisa of judgments of the twelve gems.

This perisa is called by the Hebrews an ephod, but by the Greeks 'word of judgments', and in Greek is pronounced 'logion'. On it was placed the Revelation or Sign, and Truth [i.e. δήλωσις and άλήθεια], which are written 'Light and Perfection' by the Syrians. Therefore, from that term pronounced 'ephod' by the Hebrews, the Syrians call it sometimes 'ephodo and at other times pedtho. In the book of Kingdoms, when David says to Abiathar the priest, 'Bring me the ephod (i.e. the pedtho)',20 the priest had two items to bear, the kebinta and the perisa that was attached to it, and it is unknown which of them David referred to as ephod/pedtho. For it seems that he called the combination of the two an ephod/pedtho. But here, in this book of Exodus, where God commands Moses to make both of them, namely the kebinta and the perisa, and the words of the account of each of them are known, an unfortunate and perplexing confusion has been created by this term pedtho which was set down instead of the term kebinta, since it [the pedtho] is the name indicating the perisa of judgment, being called logion i.e.'Word', the item on which was placed the Sign and Truth.'"

[11] Though the scholion is hardly remarkable in itself, Jacob may be punning on the Syriac words for "error", "making a mistake" and "ephod" (note that he retained the word play in Exodus chapter 1). Jacob gives the Hebrew, Greek and correct Syriac words for the breast-piece, and the Greek and Syriac words for the Urim and Thummim, and refers to the passage in 1 Sam 23.9 where David asks Abiathar to bring the ephod to him.

[12] As might be expected, Jacob's version of the biblical passage that immediately preceded this scholion accords completely with Jacob's definition of the correct usage of the terms perisa and kebinta. Jacob's version also diverges from the confusing terminology of the Peshitta, which uses pedtho and husoyo for the same item, and he rejects the Syrohexapla's use of pedtho.

[13] (Underlining indicates material that is unparalleled in existing witnesses to the Peshitta, Syrohexapla or LXX, and thus is apparently unique to Jacob's version in that particular place.)

Exod 28.22-30- You shall make upon the perisa 21 paired chains, braided work of pure gold.

- You shall make for the perisa 22 two clasps of pure gold and you shall bind the two clasps to the two sides of the perisa.

- You shall lay the two braids of gold in the two clasps on the two sides of the perisa.

- and the two ends of the two braids you shall tie to the two settings. You shall fasten them on the shoulders of the kebinta,23 opposite its face in front.

- You shall make two clasps of gold and place them on the two sides of the perisa, on the edge that is opposite the edge of the kebinta, inside.

- You shall make two clasps of gold and place them on the two shoulders of the kebinta beneath, squarely [= Syh] opposite its face, opposite its seam above the girdle24 of the kebinta.

- He shall attach the perisa by its links, to the links of the kebinta by a blue thread, to be over the girdle of the kebinta, lest the perisa move and come apart [= Syh] from the kebinta.

- Aaron shall bear the names of the children of Israel in the perisa of the judgments upon his breast, when he enters the place of [= Syh] the sanctuary, as a memorial before God continually.

- And you shall place upon the perisa of judgements the Revelation and the Truth [= Syh]25 , and they shall be on Aaron's breast whenever he enters the place of (= Syh) the sanctuary before the Lord. And Aaron shall bear the iniquity of the children of Israel on his breast, when he enters before the Lord always [= Syh].

[14] Ultimately, while preserving the Peshitta as a base text, Jacob uses the Greek LXX as a guide to the items, rendering λόγιον as perisa and έπωμίς as kebinta. It should be noted that Exod 28.23-28 does not appear in the Old Greek (meaning the oldest stratum of the Septuagint) of Exodus, since the original Greek form was probably translated from a Hebrew Vorlage that was shorter than the one behind the present Hebrew Masoretic Text. These particular verses were added to the church's LXX by Origen from a later translation, probably that of "Theodotion", in order to represent what appeared in the current Hebrew text.26 They appear in the Syrohexapla, because it was translated from Origen's LXX text, but there they are marked by a series of asterisks in the right hand margin to indicate that they had been added in by him.27 Jacob would have understood only that Origen had corrected the LXX against the Hebrew text, and that therefore he should include those passages. Jacob omits (or never knew) the material that appears as vv. 24, 25/(29) in Wevers' edition.28 These verses also appear in Lagarde's text of the Syrohexapla and are marked with the obelus, but in the Midyat manuscript of the Syrohexapla (SyhT) they occur unmarked He may have left it out deliberately because it was obelized by Origen as not being in the Hebrew, but this cannot be proved.

[15] The Peshitta, on the other hand, follows MT very closely, but is inconsistent with its use of equivalents for Hebrew hoshen. It uses perisa for hoshen in vv.22,282, 29, 30, but husaya in vv.232, 24, 26. It is such confusion in the Peshitta that Jacob was primarily setting out to correct or adjust in this particular passage, with the help of the Greek tradition. We have confirmation of this in the scholion appended to this section in ch.28. His aims here are therefore in contrast to his procedure in the first passage from Exodus chapter 1, where the motive seemed to be solely to expand on what the Peshitta provided, using material from the Greek directly or via the Syrohexapla.

[16] Looking at the passage in more detail, Jacob has made several minor alterations, such as changing the imperative verbs to the second person singular indicative of the Greek and Syrohexapla. He has also changed the Hebraistic verbs δώσεις and hab, adapted them to the context and replaced them with his own words 'bind' and 'tie'. The phrase "And Aaron shall bear the iniquity of the children of Israel on his breast" in the last verse is very curious. The use of 'iniquity' ( cawla) is unprecedented in the Peshitta, Syrohexapla and LXX at this point. All three witnesses have 'judgment' or 'judgements'. The reading is very clear in the manuscript of Jacob's version. Scribal error through association with another similar passage has to be ruled out, since there is to be no other place in the Bible, in Syriac or Greek, that has quite this combination of words— especially with cawlo—that could lead a scribe to make an unconscious error. One can only conclude that it is deliberate, and that Jacob extrapolated the idea of iniquity from the idea of judgement. It is not unknown for Jacob to add his own glosses to the biblical text, but this is probably the most striking instance I have come across in his version of Genesis or Exodus.29

[17] Overall, the structure and most of the terminology in these verses, apart from that concerning the perisa and pedtho, remain recognisably those of the Peshitta. The passage reflects more care and attention than Jacob often gives to the text of his own version. It is notable that there are several, rather briefer, scholia in the manuscript on other items in the Tabernacle account such as the hangings of the court of the Tabernacle,30 the order of the gems on the high priest's breast piece,31 the turban,32 the settings,33 how much 20 oboloi are worth.34 In Jacob's version of Samuel he rewrote 1 Samuel 21 very carefully: this passage about David asking for the shewbread from the priest at Nob also concerns priestly activity,35 and it is tempting to speculate that Jacob was rather interested in vestments and rules for the sanctuary. It should go without saying that in his scholia in Exodus Jacob is only concerned with the sense of passage and what all these items were: there is no attempt to use typology or allegory, and his approach is solidly historical and literal.

Conclusion[18] In contrast to the findings of Goshen Gottstein and Baars, who believed that Jacob's version was an eclectic combination of the Peshitta and Syrohexapla,36 it is very clear in these two passages from, Exodus that whether Jacob was expanding a particular passage or correcting details, Jacob's text base was certainly the Peshitta. Furthermore, he preferred to add to the Peshitta base text rather than make major changes, unless it was inadequate or confusing. Importantly, it also appears that on the whole he avoided depending too much on the Syrohexapla, preferring to make his own renderings of words directly from the Greek.37 Perhaps Jacob thought the kind of text he had created would appeal to those who disliked the Syriac style of the Syrohexapla and the way in which it completely ignored the wording of the Peshitta. Maybe Jacob's version also enabled its readers to connect with Greek exegesis without abandoning their native Syriac scripture. The result of Jacob's work was or create a kind of hybrid that amplified and clarified both the Peshitta and Greek texts of Scripture, and from a purely exegetical viewpoint it could even be considered to be superior to either tradition on its own.

_______

Notes

† An earlier version of this paper was

presented at the IX Symposium Syriacum in Kaslik, Lebanon,

September 2004.

_______

BibliographyAbbeloos, J.B. and T.J. Lamy (eds.) Gregorii Barhebraei Chronicon Ecclesiasticum. Tom. I. Louvain: Peeters, 1872.

Baars, W. "Ein neugefundenes Bruchstück aus der syrischen Bibelrevision des Jakob von Edessa." Vetus Testamentum 18 (1968): 548-54.

Brock, S.P. "From Antagonism to Assimilation: Syriac Attitudes to Greek Learning." In East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the formative period. Dumbarton Oaks Symposium 1980, ed. Nina G. Garsoïan, Thomas F. Mathews, and Robert W. Thomson. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University, 1982. 17-34.

— "Towards a history of Syriac translation technique", III Symposium Syriacum, ed. R. Lavenant. OCA 221. Rome: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1983. 1-14.

— The Bible in the Syriac Tradition. SEERI Correspondence Course (SCC) on Syrian Christian Heritage I. Kottayam, Kerala: SEERI, 1989.

— "Mingana Syr. 628: A folio from a revision of the Peshitta Song of Songs." JSS 40 (1995): 39-56.

— The Recensions of the Septuaginta Version of I Samuel. Quaderni di Henoch 9. Turin: Silvio Zamorani, 1996.

Bugati, C. Daniel secundum editionem LXX. interpretum ex tetraplis desumptum. Milan: 1788.

Ceriani, A.M. Monumenta sacra et profana, II/1. Milan: 1863.

— Monumenta sacra et profana, V/1. Milan: 1868.

— Monumenta sacra et profana ex codicibus praesertim bibliothecae Ambrosianae tom. VII. Codex Syro-hexaplaris Ambrosianus, photolithographice editus. Milan: J.B. Pogliani, 1874.

Eichhorn, J.B. Allgemeine Bibliothek 2 (1789): 270-293.

Fraenkel, D. "Die Quellen der asterisierten Zusätze im zweiten Tabernakelbericht Exod 35-40," in Studien zur Septuaginta-Robert Hanhart zu Ehren aus Anlaß seines 65. Geburtstages. eds. D. Fraenkel, U.Quast, and J.W. Wevers. MSU XX. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1990. 140-86.

Gottstein, M.H. "Neue Syrohexaplafragmente." Biblica 37 (1956): 162-183.

Hjelt, A. Études sur l'Hexaméron de Jacques d'Edesse, notamment sur ses notions géographiques contenues dans le 3ième traité. Helsingfors: J.C. Frenckell, 1892.

L'Abbé Martin, "L'Hexaméron de Jacques d'Édesse." Journal Asiatique, 8ème sér., 11 (1888): 155-219; 401-90.

Michaelis, J.D. Orientalische und exegetische Bibliothek 18 (1782): 180-183.

O'Connell, K. G. The Theodotionic Revision of the Book of Exodus : a contribution to the study of the early history of the transmission of the Old Testament in Greek. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972.

de Sacy, S. "Notice d'un Manuscrit syriaque, contenant les livres de Moïse." Notices et extraits des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale IV (1798-99): 648-668.

Saley, R.J. The Samuel Manuscript of Jacob of Edessa. A Study in Its Underlying Textual Traditions. MPIL 9. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1998.

Salvesen, A.G. "Hexaplaric Sources in Isho'dad of Merv", in The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation, ed. J. Frishman and L. Van Rompay. TEG 5. Louvain: Peeters, 1997. 229-53.

— "An edition of Jacob of Edessa's version of Samuel" in Symposium Syriacum VIIum, ed. R. Lavenant, S.J., OCA 256. Rome: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1998. 13-22.

— The Books of Jacob in the Syriac Version of Jacob of Edessa. MPIL 10. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1999.

— "The Genesis Texts of Jacob of Edessa: a Study in Variety", forthcoming.

Ugolini, M. "Il Ms. Vat. Sir. 5 e la recensione del V.T. di Giacomo d'Edessa." OrChr 2 (1902): 412-413.

Wevers, J.W. Text History of the Greek Exodus MSU XXI. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992.

Wevers, J.W., with U. Quast, Septuaginta. Vetus Testamentum Graecum auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum. Exodus. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1991.

Zotenberg, H. Manuscrits orientaux. Catalogues des manscrits syriaques et sabéens (mandaïtes) de la Bibliothéque Nationale. Paris, 1874.

Footnotes

1 I am grateful to the Peshitta Institute, Leiden, for lending me a microfilm of this manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale 26.

2 Notably in the margin of the eighth century Ambrosian Syro-Hexapla to Isa 9.6 (A.M. Ceriani, Monumenta sacra et profana ex codicibus praesertim bibliothecae Ambrosianae tom. VII. Codex Syro-hexaplaris Ambrosianus, photolithographice editus (Milan: J.B. Pogliani, 1874), folio 176r. For another, anonymous, revision based on the Greek, see S.P. Brock, "Mingana Syr. 628: A folio from a revision of the Peshitta Song of Songs" (JSS 40 [1995]), 39-56.

3 See A.G. Salvesen, "Hexaplaric Sources in Isho‘dad of Merv", in The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation, ed. J. Frishman and L. Van Rompay. TEG 5 (Louvain: Peeters, 1997), 229-53.

4 See S.P. Brock, The Bible in the Syriac Tradition. SEERI Correspondence Course (SCC) on Syrian Christian Heritage I (Kottayam, Kerala: SEERI, 1988), 20-23. However, perhaps the statement on the version of Jacob of Edessa, that Jacob "undertook another translation from Greek, but also keeping some elements from the Peshitta" should now be nuanced, at least with regard to the versions of Genesis, Exodus and Samuel.

5 On the increasing prestige of Greek learning among Syriac-speakers, see S.P. Brock, "Towards a history of Syriac translation technique", III Symposium Syriacum, ed. R. Lavenant. OCA 221. (Rome: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1983), 4-5, and idem, "From Antagonism to Assimilation: Syriac Attitudes to Greek Learning" in East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the formative period. Dumbarton Oaks Symposium 1980, eds. Nina G. Garsoïan, Thomas F. Mathews, and Robert W. Thomson (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University, 1982) 17-34.

6 S.P. Brock, "From Antagonism to Assimilation: Syriac Attitudes to Greek Learning" in East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the formative period. Dumbarton Oaks Symposium 1980, eds. Nina G. Garsoïan, Thomas F. Mathews, and Robert W. Thomson (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University, 1982) 18.

7 Gregorii Barhebraei Chronicon Ecclesiasticum, ed. J.B. Abbeloos and T.J. Lamy (Louvain: Peeters, 1872) I, cols. 291-3.

8 A.G. Salvesen, The Books of Jacob in the Syriac Version of Jacob of Edessa. MPIL 10 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1999): edition p.90 and translation p.67.

9 R.J. Saley, The Samuel Manuscript of Jacob of Edessa. A Study in Its Underlying Textual Traditions. MPIL 9 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1998), 19-38.

10 Bibliothèque Nationale 26, folio 339.

11 J.D. Michaelis, Orientalische und exegetische Bibliothek 18 (1782) 180-183 [Gen 49.2-11]; C. Bugati, Daniel secundum editionem LXX. interpretum ex tetraplis desumptum (Milan, 1788), xi-xvi, 150-151, 157-158 [Gen 11.1-9; Gen 49.2-11; Dan 1.1-6; Dan 9.24-27; Sus 1-6] (reprinted in J.B. Eichhorn, Allgemeine Bibliothek 2 [1789] 270-293); A.M. Ceriani, Monumenta sacra et profana II/1 (Milan, 1863), x-xii [Gen 4.8-16; Gen 5.21- 6.1]; A.M. Ceriani, Monumenta sacra et profana, V/1 (Milan, 1868) 8-12; 21-23; 25-38 [Isa 28.1-21; 45.7-16; 46.2-49.25]; L'Abbé Martin, "L'Hexaméron de Jacques d'Édesse" (Journal Asiatique (8ème sér.) 11 [1888] 155-219; 401-90; A. Hjelt, Études sur l'Hexaméron de Jacques d'Edesse, notamment sur ses notions géographiques contenues dans le 3ième traité (Helsingfors: J.C. Frenckell, 1892) [Gen 1.9-10]; M. Ugolini, "Il Ms. Vat. Sir. 5 e la recensione del V.T. di Giacomo d'Edessa" (OrChr 2 [1902]), 412-413 [Ezek 7.1-13]; M.H. Gottstein, "Neue Syrohexaplafragmente" (Biblica 37 [1956]) 162-183 [1 Sam 7.5-12; 20.1-23, 35-42; 2 Sam 7.1-17; 21.1-7; 23.13-17]; W. Baars, "Ein neugefundenes Bruchstück aus der syrischen Bibelrevision des Jakob von Edessa" (Vetus Testamentum 18 [1968]), 548-554 [Wis 2.12-24].

12 M.H. Gottstein, "Neue Syrohexaplafragmente"(Biblica 37 [1956]), 175-183, R.J. Saley, The Samuel Manuscript of Jacob of Edessa. A Study in Its Underlying Textual Traditions. MPIL 9 (Leiden:E.J. Brill, 1998), and A.G. Salvesen, The Books of Jacob in the Syriac Version of Jacob of Edessa. MPIL 10 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1999).

13 Sylvestre de Sacy, "Notice d'un manuscrit syriaque, contenant les livres de Moïse", Notices et extraits des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale, vol. IV (Paris 1798-99) 648-668. For a description of the manuscript, see the catalogue of H. Zotenberg, Manuscrits orientaux. Catalogues des manuscrits syriaques et sabéens (mandaïtes) de la Bibliothéque Nationale (Paris 1874) 10. See also A.G. Salvesen, "The Genesis Texts of Jacob of Edessa: a Study in Variety" [forthcoming].

14 Margin: "and fight us and go up from the land" = Peshitta.

15 Margin: "Heliopolis" = Syh.

16 Margin: "by force" = Syh.

17 The order of names is in accordance with the Greek tradition, and also to the Peshitta MS 5b1.

18 Jacob preserves the wordplay of the Peshitta, "midwives", "keep alive" and "lively", which is lost in Greek and thus in Syh also.

19 R.J. Saley, The Samuel Manuscript of Jacob of Edessa. A Study in Its Underlying Textual Traditions. MPIL 9 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1998), 19-38, 118-22.

20 Jacob's own version of this phrase in 1 Sam 23.9 (as also 23.6) uses the word 'ephod. However, he uses pedtho in 1 Sam 22.18 "priests bearing the linen ephod", and kebinta to describe the location of Goliath's sword, hidden behind the ephod (1 Sam 21.10). At 2 Sam 6.14 Jacob has cestla, perhaps because David was not a priest.

21 The same word appears in the Peshitta of this verse. LXX has λόγιον and Syh pedtho. The underlying Hebrew word is hoshen, NRSV "breast piece".

22 Here and in the next two occurrences in this verse the Peshitta uses the term husaya, which is most confusing. Jacob, Syh and LXX all maintain their equivalents from the previous verse.

23 The Peshitta uses the term pedtho in each case where Jacob employs Syh's kebinta, which itself follows LXX έπωμίς.

24 hemyana: the word is the same in the Peshitta. LXX has μηχάνωμα and Syh methaqnutha. The Hebrew word is hesheb, translated as "decorated band" in NRSV.

25 I.e. the Urim and Thummim.

26 J.W. Wevers, Text History of the Greek Exodus MSU XXI (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992), 9, 125; K. G. O'Connell, The Theodotionic Revision of the Book of Exodus: a contribution to the study of the early history of the transmission of the Old Testament in Greek (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972); cf. also D. Fraenkel, "Die Quellen der asterisierten Zusätze im zweiten Tabernakelbericht Exod 35-40," in Studien zur Septuaginta- Robert Hanhart zu Ehren aus Anlaß seines 65. Geburtstages. eds. D. Fraenkel, U.Quast, and J.W. Wevers. MSU XX (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1990), 140-86.

27 SyhT misplaces the asterisks so that they run beside vv.24-29.

28 J.W. Wevers, with U. Quast, Septuaginta. Vetus Testamentum Graecum auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum, II, I. Exodus.(Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1991), 320.

29 The nearest similar expressions in a comparable context occur in Lev 22.16 "they shall bear upon them the iniquity and sins", and Num 18.1 "bear the iniquity of the sanctuary... bear the iniquity of your priesthood", also Ezek 4.5,6 "you shall bear the iniquity of the house of Israel". But it is hard to see how these passages could have caused an unconscious error in Jacob's version of Exod 28.30. Exod 28.38, which occurs close to the passage under discussion, has the phrase "Aaron shall bear the sins of the holy things" in both the Peshitta and Jacob's version of Exod, but the use of "sin-offerings" seems to exclude it as a possible influence.

30 At the bottom of folio 161 column a, in the middle of Exod 27.16, where the column has been left one line short to accommodate it.

31 At the bottom of folio 163 column a, where two lines have been left to accommodate it.

32 Towards the bottomof folio 165 column a, where the scholion has been inserted into the biblical text.

33 On folio 162, added in the bottom margin.

34 In the bottom margin of folio 169 column a (to Exod 30.13).

35 See A.G. Salvesen, "An edition of Jacob of Edessa's version of Samuel" in Symposium Syriacum VIIum, ed. R. Lavenant, S.J., OCA 256 (Rome: Pontificium Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1998),13-22.

36 M.H. Gottstein, "Neue Syrohexaplafragmente" Biblica 37 (1956) 162-83, compared some texts in Samuel with the Syrohexapla, and in passing with the LXX and Peshitta. W. Baars, "Ein neugefundenes Bruchstück aus der syrischen Bibelrevision des Jakob von Edessa" VT 56 (1968) 548-554, compared the fragments of Jacob in Wisd with the Syrohexapla and the Peshitta.

37 Note that these findings are in line with those of S.P. Brock, The Recensions of the Septuaginta Version of I Samuel. Quaderni di Henoch 9 (Turin: Silvio Zamorani, 1996), 26-27.