Revisiting the Daughters of the Covenant: Women’s Choirs and Sacred Song in Ancient Syriac Christianity†

The Daughters of the Covenant held a distinctive office in Syriac Christianity, notable (and possibly unique) for its public ministry of sacred music performed for liturgical purposes in civic churches. Syriac tradition ascribed the establishment of these choirs of consecrated virgins to Ephrem Syrus. Jacob of Serug’s Homily on St. Ephrem presents these choirs as modeling soteriological as well as eschatological significance for the larger church community. This paper examines the context and content of what these choirs sang, in order to assess what authority this ministry carried for the ancient Syriac churches, and to suggest possible social implications.

[1] Among modern scholars, one of the best known characteristics of ancient Syriac Christianity is the institution of the Sons and Daughters of the Covenant, the Bnay and Bnat Qyama. Apparently originating in the third century CE, the office was characterized by vows of celibacy, voluntary poverty, and service to the local priest or bishop. Members were supposed to live separately with others of the same office, or with their families. The office appears to have been wide-spread in Syriac-speaking territories both east and west by the fourth century.1 The early fourth century Acts of the Edessan Martyrs Shmona and Guria note that Daughters of the Covenant were being specially targeted, along with priests and deacons, for public torture and execution during the Diocletianic persecution, attesting their public prominence.2 The Acts of the Persian Martyrs shortly thereafter recall similar treatment of Daughters of the Covenant during the persecutions of Shapur II.3 Among the first group of Demonstrations written by Aphrahat the Persian Sage in 337 is the renowned Demonstration 6, on the Members of the Covenant.4 The treatise is a lengthy exhortation addressed particularly to the men of that group on the importance of maintaining their vows of celibacy, and on the eschatological significance of those vows. In the fifth century, evidence increases with references from canonical legislation, historical chronicles, homiletic and hagiographical literature all contributing to form a picture of a church office of men and women actively engaged in civic ecclesiastical activity, in terms that rendered it quite distinct from the contemporaneously developing monastic movement. Indeed, monasticism did not replace this office. References continue certainly until the tenth century and more rarely into the middle ages.5

[2] On closer examination, however, evidence for the office of Covenanter is frustratingly thin. References may abound, but they are often only that: passing mention that Members of the Covenant were included in an incident. Most frustrating of all, at least for the historian of women, is that the majority of references to this office specifically refer to the men—the Sons of the Covenant. These are the primary addressees and concern of Aphrahat’s Demonstration 6 in the fourth century; they are the primary target of Rabbula’s canonical legislation in the fifth century, and they are the most frequently mentioned in historical texts. If we want to understand this office as it was exercised by women, we have precious little with which to work.

[3] Given the elusive nature of the evidence, recent scholarship—notably by Robert Murray, Sidney Griffith, and Naomi Koltun-Fromm—has focused on understanding the nature of the vow that underlay the office, and the perceived meaning or role of the Members of the Covenant within the larger congregation of Christian believers.6 From a different vantage point, other scholars, including Joseph Amar, Kathleen McVey, and myself, have drawn attention to an important but little considered aspect of the work of the female members of this office: that of the liturgical choirs of the Daughters of the Covenant.7 For one thing we do know is that Daughters of the Covenant were charged with the task of singing psalms and various kinds of hymns in certain liturgical celebrations of the civic churches. This practice contrasted sharply, for example, with the normal pattern of Greek and Latin civic churches to the west. These areas permitted women’s singing in convent choirs, to be sure. But with the possible exception of Ambrose’s cathedral in Milan, women’s voices were excluded from choral participation in civic liturgical celebration.8 In other words, one of the most visibly concrete forms of public ministry conducted by the Daughters of the Covenant was that of sacred music, performed in the congregational gatherings of the larger church community, male and female, ordained and lay. In this study, I would like to consider what we know about this musical ministry of the Daughters of the Covenant, and what the implications of that ministry may have been for the public place of women in late antique Syriac Christianity.

Singing Women[4] The first explicit reference we have for the liturgical singing of the Daughters of the Covenant comes in the fifth century Rabbula Canons.9 Canon 20 of this collection assigns the Daughters of the Covenant the mandatory task of singing the Psalms and especially the doctrinal hymns (madrashe) of the church. Further, canon 27 requires the Daughters of the Covenant to observe the worship services of the church, including the daily offices, together with the other clergy and the Sons of the Covenant. Other canons of this collection prohibit the clergy and Sons of the Covenant from requiring non-religious services of the Daughters of the Covenant (e.g., housekeeping or weaving), and restrict the social and economic activities available to these women. Canons 12, 15, and 19 call for village and town churches to provide the economic support necessary for poor Sons and Daughters of the Covenant, thereby safeguarding their liturgical duties on behalf of the church community.

[5] It is interesting to note that the liturgical role assigned to the Daughters of the Covenant, of psalmody and singing the madrashe, granted these women a more central function in the ritual life of the Christian community than that accorded deaconesses or widows at this time. Church orders and canon collections of the period severely limit the devotional activities of widows, confining them largely to prayer practices in their homes or in churches. Deaconesses were accorded more socially substantive duties. They were allowed to visit and instruct female catechumens and women who were ill; they assisted at the baptism of women, and were charged with keeping order in the women’s sections of the churches during liturgies. However, their ministry was clearly marked as one by women, for women.10 By contrast, the role of civic liturgical singing placed the Daughters of the Covenant in the midst of the entire worshipping community.

[6] Around the same time the Rabbula Canons were collected, the Synod of 410 was convoked by Maruta of Maipherqat for the Church of the East in Persia. Among the canons of this Synod, a number address the importance of cultivating the order of the Members of the Covenant particularly in the villages, to provide a pool for clergy and to assist in the maintenance of a devotional life for the churches in sparsely populated regions.11 Further canons clarified the ordering of women's ministry: "It is the will of the general synod that the town churches shall not be without the order [taxis] of sisters" (canon 41).12 The Daughters of the Covenant were to be under the direction of a superior chosen from among them and made a deaconess for service at baptisms; under her supervision, they were to be instructed in Scripture and in psalmody. These canons appear to have been widely used among western and eastern Syriac communities, and similar instructions are found in the sixth century canons attributed to John of Tella (Iohannan bar Qursos).13

[7] An example of the situation envisioned here is the case recorded by John of Ephesus in the sixth century, of the holy man Simeon the Mountaineer.14 Wandering the eastern borders between Roman and Persian territory as a recluse, Simeon stumbled on a remote, widely scattered semi-nomadic community that had no apparent Christian presence. Immediately Simeon set about evangelizing and baptizing the villagers, building a church, and establishing a canonically governed ecclesiastical life for the people. One of his first tasks was to round up the children, lock them inside the church (under the pretense of giving them special gifts!) and tonsure them as Sons and Daughters of the Covenant. When some families protested, their children were struck dead in divine punishment. But those who remained in their new office, Simeon instructed in a special school in scripture and psalmody, and "thenceforward loud choirs were to be heard at the service." As the years went by, these children grew to become "readers and Daughters of the Covenant, and they were themselves teaching others also." Thus Simeon did not fear his old age and approaching death when the time came, for through these Members of the Covenant the Christian life of the villagers would continue in proper order.15

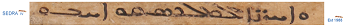

[8] It is often the case, however, that Syriac writers refer to virgins singing psalms or hymns without explicitly identifying them as Daughters of the Covenant. Whether this is due to a pragmatic flexibility of terminology, or to diversity of ecclesiastical practice—or simply to a looser mode of institutionalization than characterizes later practice—is unclear. Scholars have tended to read all references to consecrated virgins as indicating Daughters of the Covenant; perhaps the terms could be inclusive of all “virgins” who might participate, including the young unmarried girls who were not necessarily dedicated to life-long celibacy. In his hymns, Ephrem Syrus (d. 373) occasionally refers to choirs of women, apparently consecrated virgins, singing his compositions. For example, in Hymns on Nativity 4:

“ May the chant of chaste women please You, my Lord, May the chant of the chaste women dispose You, my Lord, To keep their bodies in chastity.16 ”Similar references are sprinkled throughout subsequent Syriac hymnography.17 In a homily on the Visitation of Mary to Elizabeth, Jacob of Serug (d. 521) presents Mary exhorting a women’s choir to song:

“ Let all the multitude of virgins praise Him with wonder, Because the great savior shines forth from them to the whole world. Let the voice of the young women be lifted up in praise, Because by one of them, behold, hope is brought to the world.18 ”[9] Ephrem and Jacob are in fact the most important sources for our understanding of the Daughters of the Covenant as liturgical singers. Perhaps the most cautious reading would be to see a certain melding of traditions that becomes settled in the sixth century. In the passage I just quoted, Jacob purports to speak in the voice of the Virgin Mary as she addresses her cousin Elizabeth. Her words summon forth the women’s choirs who would come to sing the hymns assigned by the canonical sources. It is from Jacob that we have our most extensive description of these choirs, which he does not name as Daughters of the Covenant. In his panegyric homily in commemoration of Ephrem,19 Jacob claims that Ephrem himself had founded the choirs of consecrated virgins. Jacob defends the tradition, boldly citing sacramental authority for the justification of women’s choirs in the church: by one baptism are men and women cleansed, he declares, and from one eucharist do they receive. Christ offers one salvation for all people, male and female, therefore all are free to sing God's praise. Jacob further argues from Eve-Mary typology, that where Eve had closed the mouths of women in shame, Mary had opened them in glory.

[10] According to Jacob, Ephrem had founded these choirs explicitly to instruct the congregation of Edessa in right doctrine. Roughly contemporary with Jacob's discussion of Ephrem, the Syriac Vita Ephraemi (6th century) identified these women's choirs specifically as composed of the Daughters of the Covenant, whom Ephrem convened for the morning and evening services in the church at Edessa and at the memorial services of saints and martyrs.20 Both depictions are notable for their emphasis on the instructional role these choirs played in educating the larger Christian community in matters of orthodoxy and heresy. Jacob, in fact, frankly names the women in these choirs malpanyatha, teachers.21 The term Jacob uses is the feminine form of malpana (masc. Teacher), one of the most revered titles in Syriac tradition, indicating not only the teaching of the Syriac language, but further, its proper (doctrinal) understanding.22 Its application to women, especially with respect to religious instruction, is startling. According to the Vita, Ephrem trained the Daughters of the Covenant to sing a variety of hymnography: doctrinal hymns (madrashe), antiphons ('ounyatha), and other kinds of songs (seblatha and qinyatha). To these melodic forms, the Vita continues,

“ [Ephrem set words] with subtle connotation and spiritual understanding concerning the birth and baptism and fasting and the entire plan of Christ: the passion and resurrection and ascension and concerning the martyrs. ... [W]ho would not be astounded nor filled with fervent faith to see the athlete of Christ [Ephrem] amid the ranks of the Daughters of the Covenant, chanting songs, metrical hymns, and melodies!23 ”[11] According to the Vita Ephraemi, then, the Daughters of the Covenant were trained to sing on matters explicating the entire salvation drama, as well as the devotional life of Christians, and about the saints—almost the exact list of topics expressly forbidden for widows to teach about in the Syriac Didascalia Apostolorum!24 But thus, by the sixth century, the Syriac practice of women’s choirs and the musical ministry of the Daughters of the Covenant had received the unequivocal authority of Ephrem as founding father.

[12] The musical ministry of the Daughters of the Covenant was further confirmed at the East Syriac Synod of Mar George I in 676, where Canon 9 identifies the most important work of these women as the chanting of the psalms at the offices of the church, as well as the singing of hymns in funeral processions (but not at the cemetery), at the memorial services for the dead, and at vigil services.25 After the seventh century, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between the offices of deaconess and Daughter of the Covenant, whose roles and functions seem eventually combined into a skeleton of their earlier duties. In the ninth century, ps-George of Arbela states (rather grumpily) that congregations must endure women’s choirs because the women represent the Egyptians and Babylonians, under whose domination the Israelites were kept enslaved: the faithful must not forget the role of humiliation in the divine dispensation.26 In the Middle Ages, the term Daughter of the Covenant appears to have become synonymous with "nun".27 However, there is a poignancy in the witness offered by one late manuscript giving a service of ordination for deaconesses in which the terms "deaconess" and "chantress" are used interchangably.28 Perhaps we might see this as a lingering memory of the importance of the choirs of the Daughters of the Covenant in the liturgical life of the larger church community—choirs whose function was not simply to sing the responses (as in the Testament of Our Lord, 40), nor only to chant the Psalms, but further, to instruct the congregation through hymnography in the substance and form of right belief.

Teaching Women[13] What did the Daughters of the Covenant sing? Elsewhere, I have been trying to address this question.29 It is, I think, crucial to consider the types and forms of hymnography sung by these choirs in liturgical settings, for the civic churches.30 I sketch the issues in summary fashion here, but I hope their significance will be clear, in light of the kind of evidence we have just been considering. Syriac Christianity has always placed enormous weight on the instructional role of the liturgy—on the liturgy as the primary teaching context of the church.31 Two areas of the liturgy were explicitly utilized for this purpose: homilies (mimre) and hymns (madrashe). The madrashe were the most important form of hymn used for this purpose, but not the only one; and madrashe themselves were of varied kinds. One of the favorite types of teaching employed by Syriac homilists and hymn writers was the presentation of biblical stories in imaginatively elaborated form, starting from the base of a biblical text and re-telling the story through the eyes—and especially through the imagined words—of its characters.32 The rhetorical technique of imagined speech, sometimes in the form of soliloquies and sometimes in dialogue with other biblical characters, was an often used and brilliantly engaged aspect of Syriac homiletic and hymnographic instruction. Among the vast corpus of such texts surviving to us (by Ephrem, Jacob of Serug, Narsai, and the whole host of anonymous authors and composers), a sizeable portion present the stories of biblical women: Sarah the wife of Abraham, Tamar, Potiphar’s Wife, the Widow of Sarepta, the Virgin Mary, the Sinful Woman who anointed the feet of Christ with her tears (in Syriac tradition, not to be confused with Mary Magdalene). In the hands of Syriac writers, this meant composing long and sometimes elaborate speeches and dialogues for female characters whom the Bible made important, but who in their scriptural texts were silent or barely granted brief comments. Major theological themes were addressed through this means, as well as matters of social and religious tension.33

[14] These different literary forms were performed in liturgical settings in a variety of ways, each carrying different ritual significance. The madrashe—such as Ephrem’s Hymns on the Nativity, in which Mary’s voice is a frequent and extensive feature of the hymns—were often sung by women’s choirs. Some madrashe were stanzaic with a refrain; the male leader (Ephrem) may have sung the stanzas, and the women’s choirs the refrain, or the choirs may have sung the stanzas and the congregation the refrain. Sogyatha, dialogue hymns, were sung antiphonally, apparently by both male and female choirs. These often presented a biblical story through an imagined dialogic exchange between the characters (Sarah and Abraham, Mary and the Archangel Gabriel or Joseph, the Sinful Woman and Satan). In these cases, the woman’s voice was sung by the women’s choir. The verse homilies (mimre), by contrast, would have been chanted by the male preacher. In the case of Jacob of Serug’s homilies on Mary, for example, these would include long passages of Mary’s imagined speech, but presented through the intoned voice of the male homilist. Certainly it is crucial to read and interpret these texts with consideration of their literary forms and constraints (meter, strophes, stanzas, responses; the presentation of narrative, exegetical exposition, speech in monologue or dialogue). Yet I would argue that it is equally critical to consider the performative requirements of the composer’s chosen form, and how performance would have shaped presentation. What was said in an imagined dialogue, in the retelling of a biblical story, in the recalling of a saint’s holy life (as in Jacob’s homily on Ephrem), was qualitatively changed by who said it, from what narrative perspective, in what ritual context, and with what performative features.

[15] In performance, Syriac hymns and homilies differed in the degree to which they were inclusive of women’s voices in the ritual context of their presentation. In content, they also differed in where and when they located the voices of female characters. Ephrem often elided biblical past and historical present, locating women’s sacred speech from the mythic (biblical) past in the midst of the gathered congregation in its present worship. The dialogue hymns performed women’s voices as liturgical drama, setting women’s voices in high relief; yet these hymns placed their voices within specific narrative moments of the church’s salvation story, as characters from a past event. A homilist such as Jacob of Serug would enclose women’s voices within the clear boundaries of narrated story and right interpretation, and within that narration construct the socially and culturally appropriate constraints on female speech. Intoned in the spaces of civic ritual through the mediation of a male priest, these words would then be echoed by the ritually authorized and ritually contained voices of women’s choirs.34 I suggest that these different modes of performance all contributed substantially to the teaching presented through the story at hand. Women’s voices imagined and real were necessary to that teaching. How were those voices heard?

Redeeming Women[16] The only extensive discussion we have of these women’s choirs is found in Jacob of Serug’s homily on Ephrem. Indeed, the space alone that Jacob allots to the matter is striking: in a panegyric composed a century or more after the great saint’s death, nearly one third is devoted to women’s choirs and their singing, 47 couplets out of a possible 187. His discussion merits closer scrutiny.35

[17] In contrast to other panegyrical homilies that Jacob composed on saints—for example, his homilies on the Edessan Martyrs Shmona, Guria, and Habib, or the one on Simeon the Stylite—this one contains virtually no narrative of the saint’s life. Instead, Jacob praises Ephrem for his extraordinary skill as hymnographer, dwelling at length on the unparalleled beauty and profundity of his theological teaching. Amidst this general exaltation of Ephrem’s craft, Jacob claims that Ephrem founded choirs of women where there had been none. Ephrem was initially prompted to do so, Jacob says, because in the task of composing hymns and homilies adequate for teaching God’s truth, he realized the eschatological significance of women’s participation.

“40. Our sisters also were strengthened by you [O Ephrem] to give praise, For women were not allowed to speak in church. [cf. 1 Cor 14:34]

41. Your instruction opened the closed mouths of the daughters of Eve; And behold, the gatherings of the glorious (church) resound with their melodies.

42. A new sight of women uttering the proclamation (karuzutha); And behold, they are called teachers (malpanyatha) among the congregations.

43. Your teaching signifies an entirely new world; For yonder in the kingdom (of heaven), men and women are equal.

44. You labored to devise two harps for two groups; You treated men and women as one to give praise.

”[18] According to Jacob, then, Ephrem’s choirs do more than proclaim that with Christianity a new era has dawned for humanity. They enact that new dispensation by the very fact that they include female as well as male voices. The use of these choirs is startling: despite the Pauline admonition for women’s silence, Ephrem presents his church with “a new sight of women uttering the proclamation.” Nor does Jacob pull punches here. The term he uses is karuzutha, the Syriac equivalent for kerygma. These women sing the full doctrinal proclamation of the church. Rightly so, then, are “they called teachers among the congregations”. Here is his term malpanyatha; by Jacob’s reckoning, these women sing the very teaching by which Christianity exists, by which salvation has come. So dramatic is the act of women in this role, that Jacob declares it images “an entirely new world”. In Jacob’s account, just as men and women are equal in the heavenly kingdom to come, so, too, is that kingdom imaged and anticipated in the Syriac liturgy with its male and female choirs.

[19] Jacob’s defense of Ephrem then moves from eschatology to typology. Moses had led the Hebrew women in song at the crossing of the Red Sea, summoning them to celebrate the deliverance of the Hebrews from the Egyptians. So, too, did Ephrem lead the Syrian women in hymns to celebrate the deliverance of humanity from the powers of sin and death. Omitting Miriam’s role in the biblical account, Jacob presents both men as liberators who declare a new freedom of worship for women. For Jacob, Ephrem’s action is a logical result of sacramental mandate, for men and women participate in salvation by the same means, first by baptism, then by the eucharist. He portrays Ephrem calling the women to song:

“105. You [O women] put on glory from the midst of the waters like your brothers, Render thanks with a loud voice like them also.

106. You have partaken of a single forgiving body with your brothers, And from a single cup of new life you have been refreshed.

107. A single salvation is yours and theirs (alike); why then Have you not learned to sing praise with a loud voice?

”Unequivocally justified by the sacramental practices of the church, Ephrem’s choirs themselves represent a further typological fulfillment, soteriological in its impact. For Eve had closed the mouths of women in shame by her disobedience at the Fall. But the Virgin Mary opened them again, loosening their bonds, opening the closed door of their tongues, and restoring the voices of women.

“112. Because of the wickedness of Eve, your mother, you [O women] were under judgment; But because of the child of Mary, your sister, you have been set free.

113. Uncover your faces to sing praise without shame to the One who granted you freedom of speech by his birth.

”[20] By just such exhortations, Jacob declares, did Ephrem establish the women’s choirs, granting them the responsibility of chanting “instructive melodies” (qale d-malpanutha). And by such melodies were the efforts of the heretics laid low, as the church triumphed in orthodoxy through the “soft tones” of the women (vv. 114, 152).

[21] Jacob’s justification of Ephrem’s establishment of the women’s choirs is fourfold: eschatological, typological, sacramental, soteriological. So formidable is his effort, in fact, that Kathleen McVey has argued for reading this homily as a defense of women’s choirs in the wake of an ecclesiastical attack on their validity—whether from Greek churches to the west (Antioch?), or from rivalries within Syriac doctrinal circles locked in fierce debate at the time.36 But we simply cannot know. Greek sources are as silent on these Syriac choirs as were Greek women in their liturgies. In Syriac churches, the women’s choirs have continued to the present day, although Jacob’s homily is rarely remembered.37 We are left, then, with something of a puzzle: how to account for these women’s choirs of the Daughters of the Covenant, and indeed, for Jacob’s extraordinary defense of them.

[22] One other ancient source presents a fairly similar understanding of the significance of male and female choirs: Philo of Alexandria’s account of the Therapeutae, in his treatise On the Contemplative Life. Philo describes this philosophical community and its utopian (or eschatological) existence at some length. Towards the end of the treatise, in section 8, he explicitly mentions the women of the community, “aged virgins” committed as eagerly as the men to the perfect philosophical life of devotion to God. Every seven weeks, Philo says, the men and women gather for a festal banquet, the men sitting on the right and the women on the left (section 9). Following the food, instruction on the scriptures is given by the president (section 10). When the teaching is complete, first the president and then the entire community join in song. In two choirs, the men and women sing sacred hymns all night, of many kinds, of different rhythms, sometimes with clapping or dancing. Here, too, is the typology of the singing at the Red Sea recalled, and Miriam as prototype for the leader of the women’s choir, along with Moses for the men. “Modeled above all on this (the singing at the Red Sea),” Philo states, “the choir of the Therapeutae, both male and female, singing in harmony, the soprano of the women blending with the bass of the men, produces true musical concord. Exceeding beautiful are the thoughts, exceeding beautiful are the words, and august the choristers, and the end goal of thought, words, and choristers alike is piety.”38

[23] It is possible that Jacob knew of Philo’s text. Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History was available in Syriac in the sixth century, and Bk. 2, 16-7 presents a “filtered” account of Philo on the Therapeutae.39 But the descriptions diverge as much as they resonate. Even without the disputed question of whether or not the Therapeutae existed as an historical community, Philo’s account represents the ideal philosophical collective—an elite community, living apart from mundane society. Jacob’s description of the women’s choirs presents an idealized justification for the practice, to be sure. But the practice, as attested not only in Jacob but in dozens of canonical sources, was to be found in every Syriac-speaking village, town, and city of late antiquity, enacted in the civic churches of the collected populus. It offered a vision of the ideal, enacted in the midst of the ordinary.

[24] Very little evidence has survived to us regarding the pre-Christian, indigenous religions of the Syrian Orient that continued into the Christian period.40 We know the names and sometimes the symbols of deities, and occasionally titular offices. But of practices, we know almost nothing. Suggestive models can sometimes be drawn from Greek traditions to the west, however. In her book Performance and Gender in Ancient Greece, Eva Stehle discusses the significance of ancient Greek civic choruses, both male and female, in terms that help to illuminate the issues of women’s choirs in the ancient Syriac churches.41 She argues that civic choruses through their performances in religious festivals provided the embodied expression of the city itself. As such, their role was to vindicate and affirm civic order as just, good, and worthy of admiration (even devotion). The capacity for this expression lay in the chorus’ ability to reflect and model the community’s most idealized self-understanding. Reflection, oriented to the past, was offered by the chorus’ presentation of the city’s sacred past: the great events by which it was formed and bonded into a community under the gods’ protection. Modeling, in turn, was oriented toward the future: by the harmony and beauty of their performance, the chorus represented the community in its ideal form. Gender was essential to the work of these choruses, since male and female choirs performed these tasks in distinct, differentiated ways. It is helpful, I think, to consider the role of women’s choirs in the Syriac churches in these terms. Indeed, Jacob of Serug had stressed the eschatological significance of women’s choirs as signs of the resurrected life to come.

[25] Scholars have given much attention to the capacity of holy women in late antiquity to attain high levels of spiritual authority among the general populace, and to serve as spiritual teachers and counselors.42 The model of holy woman as authoritative spiritual teacher is, however, founded on a pattern of direct, even personal instruction by a mentor to a devotee. The teaching performed by the Daughters of the Covenant differed substantially from this model, both in kind and in nature. The content of their teaching was not the revealed wisdom of a holy individual, but rather the stated, collectively identified corporate doctrines of the church. These choirs through the madrashe represented to the Christian congregation the affirmed, authorized teachings they held in common. Moreover, as liturgical choirs, these women taught by their very performance the substance of their teaching: women as well as men received eschatological hope through sacramental practice.

[26] For the societies of the ancient Mediterranean, religion was the fundamental means of identity and order. In religious rituals, the community could see itself constituted and sustained, renewed and confirmed, time and again. So, too, in ancient Christianity. In his Hymns on Easter, Ephrem exhorts the church to offer fitting worship to God in these terms:

“ Let us plait a magnificent crown for [Christ our Lord]... The bishop weaves into it His biblical exegesis as his flowers; The presbyters their martyr stories; The deacons their lections, The young men their alleluias, The boys their psalms, The virgins their madrashe, The rulers their achievements, And the lay people their virtues. Blessed be the One who has multiplied victories for us.43 ”[27] Here, in splendid array, is the ancient Syriac church in glory. Essential to it is the place of the women’s choir: distinct, separated, included in the proper order, excluded from the clergy, yet uniquely the source of doctrinal truth: of right Christian faith. I suggest that we, as historians, have something more to learn here.

_______ Notes

† Earlier versions of this paper were

presented at the Syriac Symposium IV, Princeton Theological

Seminary, Princeton, New Jersey, July 2003; at the Center for

Early Christian Studies, Catholic University of America,

Washington, DC, Feb. 2004; and to the Brown Seminar on

Culture and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean, March

2004. I am grateful to participants in these occasions for

constructive conversation and helpful suggestions, and above

all to Joseph P. Amar and Sidney H. Griffith.

” _______

Bibliography

” _______

Bibliography

Amar, Joseph P. “A Metrical Homily on Holy Mar Ephrem by Mar Jacob of Serug.” PO 47 (1995): 5-76.

— idem. The Syriac “Vita” Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1988.

Aphrahat. Demonstration 6. D. I. Parisot (ed.), Aphraatis sapientis persae demonstrationes, in PS 1, R. Graffin (ed.), (Paris, 1894), 241-311. J. Gwynn (trans.) in Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers 13: 362-75.

Brock, Sebastian P. “Deaconesses in the Syriac Tradition.” In Woman in Prism and Focus: Her Profile in Major World Religions and in Christian Traditions. P. Vazheeparampil (ed.), Rome: Mar Thoma Yogam, 1996, 205-18.

— idem. Bride of Light: Hymns on Mary from the Syriac Churches. Kottayam, Kerala: SEERI, 1994.

— idem, and Susan Ashbrook Harvey. Holy Women of the Syrian Orient. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Burkitt, F. C. (ed. and trans.). Euphemia and the Goth with the Acts of the Martyrdom of the Confessors of Edessa. London: Williams and Norgate, 1913.

Burrus, Virginia. “The Heretical Woman as Symbol in Alexander, Athanasius, Epiphanius, and Jerome.”Harvard Theological Review 84 (1991): 229-48.

Chabot, J. B. (ed. and trans.). Synodicon Orientale ou Recueil de Synodes Nestoriens. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1902.

Cunningham, Mary, and Pauline Allen, eds. Preacher and Audience: Studies in Early Christian and Byzantine Homiletics. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1998.

Drijvers, H. J. W. “Solomon as Teacher: Early Syriac Didactic Poetry.” In IV Symposium Syriacum 1984. H. J. W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink (ed.). Orientalia Christiana Analecta 229 (Rome 1987), 123-34.

— idem. Cults and Beliefs at Edessa. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1980.

Elm, Susanna. ‘Virgins of God’: the Making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

Griffith, Sidney H. “‘Singles’ in God’s Service: Thoughts on the Ihidaye from the Works of Aphrahat and Ephraem the Syrian.” The Harp 4 (1991), 145-59.

— idem, “Monks, ‘Singles’, and the ‘Sons of the Covenant’: Reflections on Syriac Ascetic Terminology.” In Eulogema: Studies in Honor of Robert Taft. E. Carr et al. (ed.), Studia Anselmiana 110 / Analecta Liturgica 17 (Rome: Centre Studi S. Anselmo, 1993), 141-60.

Harvey, Susan Ashbrook. Asceticism and Society in Crisis. John of Ephesus and the 'Lives of the Eastern Saints'. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

— eadem. “Women’s Service in Ancient Syriac Christianity.” In Mother, Nun, Deaconess: Images of Women According to Eastern Canon Law. Eva Synek (ed.). Kanon 16 (Egling 2000), 226-41.

— eadem. “Spoken Words, Voiced Silence: Biblical Women in Syriac Tradition.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 9 (2001). 105-31.

— eadem. “On Mary’s Voice: Gendered Words in Syriac Marian Tradition.” In The Cultural Turn in Late Ancient Studies: Gender, Asceticism, and Historiography. Patricia Cox Miller and Dale Martin (ed.). Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005, 63-86.

Husmann, Heinrich. “Syrian Church Music.” In New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Stanley Sadie (ed.). London 1980. Vol. 18, 472-81.

Jacob of Serugh. Select Festal Homilies. Thomas Kollamparampil (trans.). Rome: CIIS, 1997.

— idem. On the Mother of God. Mary Hansbury (Trans.). Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998.

— idem. Jacques de Saroug, Homélies contre les Juifs. Micheline Albert (ed. and trans.). PO 38 (1976).

John of Ephesus. Lives of the Eastern Saints. E. W. Brooks (ed. and trans.). PO 17-19 (1923-5.)

Koltun-Fromm, Naomi. “Yokes of the Holy Ones: The Embodiment of a Christian Vocation.” Harvard Theological Review 94 (2001), 205-18.

Martimort, A. G. Les Diaconesses. Essai Historique. Bibliotheca “Ephemerides Liturgicae” Subsidia. Rome, 1982.

Mateos, Juan. Lelya-Sapra: Essai d’interpretation des matines chaldeennes. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1959.

McKinnon, James. Music in Early Christian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

McVey, Kathleen. Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns. New York: Paulist Press, 1989.

— eadem. “Were the Earliest Madrase Songs or Recitations?” In After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honor of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers. G. J. Reinink and A. C. Klugkist (ed.). Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89 (Leuven: Peeters, 1999), 185-99.

— eadem. “Ephrem the Kitharode and Proponent of Women: Jacob’s Portrait of a Fourth-Century Churchman for the Sixth Century Viewer.” (Forthcoming).

Millar, Fergus. The Roman Near East 31 BC – AD 337. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Murray, Robert. “Circumcision of the Heart and the Origins of the Qyama.” In After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honor of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers. G. J. Reinink and A. C. Klugkist (ed.). Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89 (Leuven: Peeters, 1999), 201-11.

Nedungatt, George. “The Covenanters of the Early Syriac-Speaking Church.” OCP 39 (1973), 191-215, 419-44.

Philo. On the Contemplative Life. F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker (ed. and trans.). In Philo: Works 9:112-69, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941. David Winston (Trans.). Philo of Alexandria: The Contemplative Life, The Giants, and Selections. New York: Paulist Press, 1981, 41-57.

Quasten, Johannes. “The Liturgical Singing of Women in Christian Antiquity.” Catholic Historical Review 27 (1941), 149-65.

— idem, Music and Worship in Pagan and Christian Antiquity. Boniface Ramsey (Trans.). Washington: National Association of Pastoral Musicians, 1983.

Robinson, C. The Ministry of Deaconesses. London: Methuen, 1898.

Ross, Steven K. Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114-242 CE. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Ri, Su-Min (ed. and trans.) La Caverne des Trésors les deux recensions syriaques. CSCO 486-7, Scr. Syr. 207-8 (Louvain, 1987).

Smith, J. Payne (Mrs. Margoliouth). A Compendius Syriac Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1903; repr. 1976.

Stehle, Eva. Performance and Gender in Ancient Greece: Nondramatic Poetry in its Setting. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Velimirovic, Milos. “Christian Chant in Syria, Armenia, Egypt, and Ethiopia.” In New Oxford History of Music, Vol. 2: The Early Middle Ages to 1300. Richard Crocker and David Hiley (ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, 3-9.

Vööbus, Arthur (ed. and trans.). Syriac and Arabic Documents Regarding Legislation Relative to Syrian Asceticism. PETSE 11. Stockholm: ETSE, 1960.

— idem (ed. and trans.). The Canons Ascribed to Maruta of Maipherqat and Related Sources. CSCO 439-40, Scr. Syr. 191-2 (Louvain 1982).

— idem (ed. and trans.). The Synodicon in the West Syrian Tradition. CSCO 367/8, Scr. Syr. 161/2 (Louvain 1975).

— idem (ed. and trans.). The Statutes of the School of Nisibis, PETSE 12. Stockholm: ESTE, 1962.

— idem (ed. and trans.). The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac. Vol. 1, CSCO 401-2, Scr. Syr. 175-6. Vol. 2, CSCO 407-8, Scr. Syr. 179-80. Louvain, 1979.

Wright, William, and Norman McLean (trans.). The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius, in Syriac. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898.

Footnotes

1 G. Nedungatt, “The Covenanters of the Early Syriac-Speaking Church,” OCP 39 (1973), 191-215, 419-44. At their earliest, the Daughters of the Covenant may be similar to consecrated virgins (the subintroductae, or canonicae) elsewhere in the Roman Empire, prior to the emergence of monasticism as an institution. For these, see Susanna Elm, ‘Virgins of God’: the Making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994).

2 Shmona and Guria, sec. 1, sec. 70; F. C. Burkitt (ed. and trans.), Euphemia and the Goth with the Acts of the Martyrdom of the Confessors of Edessa (London: Williams and Norgate, 1913).

3 E.g., Martha the daughter of Posi; Tarbo and her maidservant; Thekla, Danaq, Taton, Mama, Mezakhya and Anna, of Karka d-Beth Slokh; Abyat, Hathay, and Mezakhya, from Beth Garmay; Thekla, Mary, Martha, and Emmi, of Bekhashaz. All these are identified by name as Daughters of the Covenant, but more are indicated by the texts. See the episodes collected in Sebastian P. Brock and Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Holy Women of the Syrian Orient (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 63-82.

4 Aphrahat, Dem. 6, D. I. Parisot (ed.), Aphraatis sapientis persae demonstrationes, in PS 1, R. Graffin (ed.) (Paris, 1894), 241-311; J. Gwynn (trans.) in Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers 13: 362-75.

5 S. A. Harvey, “Women’s Service in Ancient Syriac Christianity,” in Mother, Nun, Deaconess: Images of Women According to Eastern Canon Law, Eva Synek (ed.), Kanon 16 (Egling, 2000): 226-41.

6 Robert Murray, “Circumcision of the Heart and the Origins of the Qyama,” in After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honor of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers, G. J. Reinink and A. C. Klugkist (ed.), Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89 (Leuven: Peeters, 1999), 201-11; Sidney H. Griffith, “‘Singles’ in God’s Service: Thoughts on the Ihidaye from the Works of Aphrahat and Ephraem the Syrian,” The Harp 4 (1991), 145-59; idem, “Monks, ‘Singles’, and the ‘Sons of the Covenant’: Reflections on Syriac Ascetic Terminology,” in Eulogema: Studies in Honor of Robert Taft, E. Carr et al. (ed.), Studia Anselmiana 110/ Analecta Liturgica 17 (Rome: Centre Studi S. Anselmo, 1993), 141-60; Naomi Koltun-Fromm, “Yokes of the Holy Ones: The Embodiment of a Christian Vocation,” Harvard Theological Review 94 (2001), 205-18.

7 Joseph P. Amar, “A Metrical Homily on Holy Mar Ephrem by Mar Jacob of Serug,” PO 47 (1995), 5-76; idem, The Syriac “Vita” Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1988); Kathleen McVey, Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns (New York: Paulist Press, 1989), pp. 28; eadem, “Ephrem the Kitharode and Proponent of Women: Jacob’s Portrait of a Fourth-Century Churchman for the Sixth Century Viewer,” (Forthcoming); S. A. Harvey, “Women’s Service;” eadem, “Spoken Words, Voiced Silence: Biblical Women in Syriac Tradition,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 9 (2001), 105-31.

8 Or so we assume. Eusebius, HE 7. 30.10, cites women’s choirs as one of the reasons for Paul of Samosata’s expulsion from Antioch, but the problem was perhaps not the women’s choirs so much as that the hymns they sang were in honor of Paul himself. Cyril of Jerusalem, Procat. 14, exhorts that women should keep absolutely silent in church; but he is speaking about catechumens preparing to receive baptism. It is not clear to me that the passage precludes choirs (although scholars have assumed it does). Ambrose, Explan. Ps. 1.9, mentions women’s singing positively, directly taking issue with the Pauline admonition that women must keep silent in church (1 Cor 14:34); he advocates the singing of psalms as beneficial for all people. Nonetheless, the references to women’s choirs that we have, e.g., in the Cappadocian Fathers, are to convent choirs of women monastics: consider Basil of Caesarea, Letter 2, and Gregory of Nyssa, Life of Macrina. See Johannes Quasten, “The Liturgical Singing of Women in Christian Antiquity,” Catholic Historical Review 27 (1941), 149-65; idem, Music and Worship in Pagan and Christian Antiquity, Boniface Ramsey (trans.), (Washington: National Association of Pastoral Musicians, 1983), 75-86. An extremely useful collection of translations of the relevant primary sources (Greek, Latin, and some Syriac) may be found in James McKinnon, Music in Early Christian Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

9 “The Rules of Rabbula for the Clergy and the Qeiama,” Arthur Vööbus (ed. and trans.), Syriac and Arabic Documents Regarding Legislation Relative to Syrian Asceticism, PETSE 11 (Stockholm: ETSE, 1960), 34-50.

10 Sebastian P. Brock, “Deaconesses in the Syriac Tradition,” in Woman in Prism and Focus: Her Profile in Major World Religions and in Christian Traditions, P. Vazheeparampil (ed.) (Rome: Mar Thoma Yogam, 1996), 205-18; A. G. Martimort, Les Diaconesses. Essai Historique, Bibliotheca “Ephemerides Liturgicae” Subsidia (Rome, 1982), esp. 21-54, 165-70; C. Robinson, The Ministry of Deaconesses (London: Methuen, 1898), esp. 169-96; Harvey, “Women’s Service.”

11 A. Vööbus, The Canons Ascribed to Maruta of Maipherqat and Related Sources, CSCO 439-40, Scr. Syr. 191-2 (Louvain, 1982).

12 Trans. in Vööbus, Canons Ascribed to Maruta, 72.

13 Canons of Iohannon bar Qursos, 27, A. Vööbus (ed. and trans.), The Synodicon in the West Syrian Tradition, CSCO 367/8, Scr. Syr. 161/2 (Louvain 1975).

14 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, ch. 16, E. W. Brooks (ed. and trans.), PO 17 (Paris 1923), 229-47. The incident is discussed in S. A. Harvey, Asceticism and Society in Crisis. John of Ephesus and the 'Lives of the Eastern Saints' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 95ff.

15 John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, ch. 16, PO 17: 246f.

16 Ephrem, Hymns on Nativity 4. 62b-63; K. McVey (trans.), Ephrem: Hymns, 93.

17 Sebastian P. Brock, Bride of Light: Hymns on Mary from the Syriac Churches (Kottayam, Kerala: SEERI, 1994), 11. 1, p. 42; 9. 1, p. 38; Jacob of Serugh, Select Festal Homilies, Thomas Kollamparampil (trans.) (Rome: CIIS, 1997), Hom. Nat. 3.27-8, 353; trans. pp. 112, 127.

18 Jacob of Serug, On the Mother of God, Mary Hansbury (trans.) (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), Homily 3, at p. 83.

19 Amar, “Metrical Homily.” Jacob claims Ephrem founded these choirs because the heretics, especially the Bardaisanites, had been successful at spreading their teachings through hymns. As to why Ephrem chose women’s choirs for this task, Jacob does not say. In the cultural coding of the ancient Mediterranean world, however, the female virgin body was the premier image for perfection, purity, and intactness. Perhaps the female virgin could thus most effectively image the presentation of true doctrine precisely as teaching that was perfect, pure, and intact from any external (unholy) penetration. Heresy was often likened to harlotry by early Christian writers; see, e.g., Virginia Burrus, “The Heretical Woman as Symbol in Alexander, Athanasius, Epiphanius, and Jerome,” Harvard Theological Review 84 (1991), 229-48. The images of Wisdom and Folly from Proverbs 8-9 provide a Biblical background for such gendered imagery.

20 Amar, The Syriac "Vita" Tradition of Ephrem the Syrian, 158f. (Syriac), 298f. (trans.).

21 Amar, “Metrical Homily,” v. 42, pp. 34-5. The passage is quoted and discussed further below.

22 Teaching, especially of sacred doctrine, is in fact a primary theme of Jacob’s Homily on Ephrem as a whole: Amar, “Metrical Homily,” p. 19. As Jesse Margoliouth points out, malpana was also a term used to designate the great doctrinal figures of Syriac tradition, such as Ephrem and Jacob. J. Payne Smith (Mrs. Margoliouth), A Compendius Syriac Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1903; repr. 1976), 278. Compare, also, the use of the term in A. Vööbus (ed. and trans.), The Statutes of the School of Nisibis, PETSE 12 (Stockholm: ESTE, 1962).

23 Amar, The Syriac "Vita" Tradition of Ephrem, 158f. (Syriac), 298f. (trans.).

24 Syriac Didascalia Apostolorum, Ch. 15; A. Vööbus (ed. and trans.), The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac, Vol. 1, CSCO 401-2, Scr. Syr. 175-6, and Vol. 2, CSCO 407-8, Scr. Syr. 179-80 (Louvain, 1979).

25 As discussed in Martimort, Les Diaconesses, 54. The text is ed. and trans. in J. B. Chabot, Synodicon Orientale ou Recueil de Synodes Nestoriens (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1902), 221-2 (Syr.), 486 (Fr.).

26 As cited by Juan Mateos, Lelya-Sapra: Essai d’interpretation des matines chaldeennes (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1959) at p. 408. Is there here a pun on bart qyama for bart qaina, alluding to the story from the Syriac Cave of Treasures, Ch. 11-12, where the Daughters of Cain seduced the Sons of God with their singing? Su-Min Ri (ed. and trans.), La Caverne des Trésors les deux recensions syriaques, CSCO 486-7, Scr. Syr. 207-8 (Louvain, 1987). The episode is especially emphasized in the East Syriac recension. I am indebted to Serge Ruzer for this suggestion.

27 E.g., canon 19 in the ninth century collection of Isho' bar Nun; Vööbus (trans.), The Canons Ascribed to Maruta, 192.

28 Brock, “Deaconesses,” 213-6, where he provides a translation of the service.

29 Harvey, “Spoken Words, Voiced Silence;” eadem, “On Mary’s Voice: Gendered Words in Syriac Marian Tradition,” in The Cultural Turn in Late Ancient Studies: Gender, Asceticism, and Historiography, Patricia Cox Miller and Dale Martin (ed.) (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 63-86.

30 Milos Velimirovic, “Christian Chant in Syria, Armenia, Egypt, and Ethiopia,” New Oxford History of Music, Vol. 2: The Early Middle Ages to 1300, Richard Crocker and David Hiley (ed.) (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 3-9; McKinnon, Music in Early Christian Literature, 92-5; Heinrich Husmann, “Syrian Church Music,” in New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Stanley Sadie (ed.)(London & Washington DC: Grove's Dictionary of Music, 1980), Vol. 18: 472-81.

31 E.g., Kathleen McVey, “Were the Earliest Madrase Songs or Recitations?”, After Bardaisan, Reinink and Klugkist (ed.), 185-99; H. J. W. Drijvers, “Solomon as Teacher: Early Syriac Didactic Poetry,” in IV Symposium Syriacum 1984, H. J. W. Drijvers, R. Lavenant, C. Molenberg, and G. J. Reinink (ed.). Orientalia Christiana Analecta 229 (Rome 1987), 123-34.

32 Detailed discussion in Harvey, “Spoken Words, Voiced Silence.”

33 Important new work is now being done particularly on Greek homiletics and the reception by congregations, that raises helpful questions for the Syriac material. See, e.g., Mary Cunningham and Pauline Allen, eds., Preacher and Audience: Studies in Early Christian and Byzantine Homiletics (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1998).

34 Harvey, “On Mary’s Voice.”

35 I will follow the translation in Amar, “Metrical Homily”. I give the verse numbers as they are in the text; in Amar’s edition, these passages come from pp. 35-65.

36 McVey, “Ephrem the Kitharode and Proponent of Women.”

37 Women’s choirs are commonplace still among the Syriac Orthodox churches. However, Archbishop Cyril Aprem has told me that the choirs are now criticized as being the result of pernicious influence from secular western feminism!

38 David Winston (Trans.), Philo of Alexandria: The Contemplative Life, The Giants, and Selections (New York: Paulist Press, 1981), 41-57, at pp. 56-7. The Greek is edited with translation by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker in Philo: Works 9:112-69, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941).

39 I owe the phrase and the reference to Anne Seville, and I am grateful for both. The text is translated in William Wright and Norman McLean, The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius, in Syriac (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898).

40 Fundamental studies are H.J.W. Drijvers, Cults and Beliefs at Edessa (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1980); Fergus Millar, The Roman Near East 31 BC – AD 337 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); and Steven K. Ross, Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114-242 CE (New York: Routledge, 2001).

41 Eva Stehle, Performance and Gender in Ancient Greece: Nondramatic Poetry in its Setting (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

42 In Greek tradition, one thinks of Macrina, the sister of Gregory of Nyssa; Gorgonia, sister of Gregory of Nazianzus; Melania the Elder and Melania the Younger; and especially Syncletica among the Desert Mothers of Egypt. In Syriac tradition, strong examples would be Febronia of Nisibis; Mary, Euphemia, and Susan from John of Ephesus’ Lives of the Eastern Saints; and Martyrius’ depiction of Shirin. For these, see Brock and Harvey, Holy Women.

43 Ephrem, Hymns on Easter 2:8-9; Sidney Griffith (trans.), cited McKinnon, Music in Early Christian Literature, pp. 93-4. The Syriac is edited by Edmund Beck, CSCO 248, Scr. Syr. 84. Compare Jacob of Serug, Hom. Against the Jews, 7. 529-42, Micheline Albert (ed. and trans.), Jacques de Saroug, Homélies contre les Juifs, PO 38 (1976), at pp. 216-7: